By Jack Brammer

Kentucky Lantern

The lean, bespectacled veteran from Kentucky sat silently in the early evening of Aug. 14 on a stage in the cavernous U.S. Freedom Pavilion in the National WWII Museum.

With vintage war planes hanging overhead from the ceiling, Sanford L. Jones Sr. of Richmond peered out at an audience of about 300, mostly tourists. With him were Emily Drake of Pennsylvania and Lewis Harned of Wisconsin, ready for a discussion to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the end of the Second World War.

The deadliest conflict in history — causing the deaths of 70 million to 85 million people, more than half of them civilians — officially came to an end on Sept. 2, 1945. Terms of surrender were signed by Japanese officials aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay and accepted by U.S. Gen. Douglas MacArthur.

On the museum stage in New Orleans, veteran Drake, a stenographer with the Women’s Army Corps during the war, was the first to take her seat. She was joined by Jones and Harned, a volunteer ambulance driver with the American Field Service

in the war and a longtime U.S. Armed Forces doctor.

Before host Peter Crean started the panel discussion, Drake softly made a comment to Jones that her microphone picked up and broadcast to the crowd.

“I’m nervous,” she said. Jones immediately replied, “Well, I am, too.”

Smatterings of laughter could be heard in the audience, then applause. It was a gesture praising three veterans who bravely offered so much during the war and now were a bit nervous before a friendly crowd. Their humility was on display.

“Well, Emily,” added Jones. “We are here because not many of us are left.”

According to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, as of January 2025, fewer than 66,000 U.S. World War II veterans remain alive out of the 16.4 million Americans who served during the war. This number represents less than 1% of the total who served. By 2034, only about 1,000 are projected to still be with us.

Museum official Crean said at the commemoration ceremony that the life of each of the three people on stage was emblematic of the strength and bravery of the men and women who served in World War II.

Here is the story of one of them, Kentuckian Sanford Logan Jones Sr.

From Lost Creek to San Giovanni and back to Lost Creek

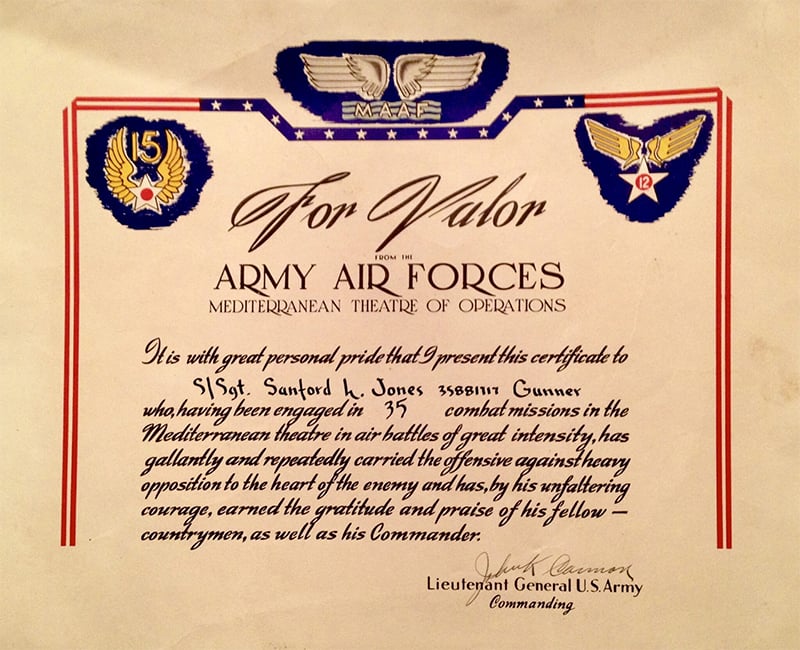

Jones was a U.S. Army Air Forces gunner on B-24 Liberators in the European theater. He received a recommendation of valor for his 35 combat missions “in air battles of great intensity.”

On Sept. 22, Jones will turn 100. He was born near Lost Creek in Eastern Kentucky’s Perry County. “It was a very isolated and rural place with no running water, no electricity, no phone,” he said.

Lost Creek, 10 miles long and mainly in Breathitt County, is a tributary of Troublesome Creek which flows into the North Fork of the Kentucky River. Many homes in the watershed were destroyed in a flash flood in July 2022.

Sanford’s father, Dave Jones, was a coal miner. His mother, Grace Elizabeth Terry, was an elementary school teacher. The couple had two girls and four boys.

Sanford attended a one-room school in Lost Creek. One teacher served eight grades. “I still can see that pot-bellied stove in that school,” he said.

He graduated from elementary school in 1940 and then attended a school in Breathitt County through his junior year.

“We were walking back home from church later that afternoon and saw a crowd at a house,” he said. “We stopped by to see what was going on and we found people listening to a Philco radio, something about the bombing of Pearl Harbor. The next day President Roosevelt talked about the day of infamy.

“The people had serious faces. I thought this will probably mean I’m going to war.”

In November 1943, before he finished high school, Jones got a draft notice from the Army in Hazard. That led him to training in a series of Army bases.

“I especially remember the marching songs I learned,” he said. “Left, right, left, right. One, two, three, four. You had a good home and you left it.”

In Biloxi, Mississippi, young Jones was assigned to a gunnery school. He was soon ready for combat. On Oct. 16, 1944, he landed at San Giovanni Airfield in Italy to join the U.S. Army 15th Air Forces, 304th Bombardment Wing, 455th Bombardment Group.

A month later, he flew his first combat mission. It was to Munich, Germany. “My responsibility on that mission was to release bundles of aluminum foil from the plane to deflect radar to keep anyone from spotting us. In other missions, I was a turret gunner.”

A turret is a revolving armored structure in aircraft that houses one or more guns and can be rotated to aim the weapons in different directions. The operator is often in a cramped, dangerous position. Jones stood 5 feet, 8 inches and weighed 137 pounds.

Jones’ combat missions were over Germany, Italy, Austria and Yugoslavia. Memories of enemy flak aimed at his plane will not be forgotten.

Was he ever scared?

“Fear is one of the most powerful emotional responses,” he said. “I just did my job but the fear was there. I always felt I was going to come back home.”

The first 100 runs of the 455th Bombardment Group were the most dangerous, Jones said. “About 75% of them were never completed.”

On May 8, 1945, after 35 combat missions, Jones was sent to Naples, Italy. On May 25, he landed in Florida and was assigned to a parts division.

On Oct. 20, 1945, Jones got his discharge papers as a staff sergeant. He rode a bus from Florida to Lexington. He then caught a bus service that put him about five miles from his Lost Creek home.

Jones arrived on foot and unannounced. “I can’t tell you the minute-by-minute reunion with my family but I know there were a lot of smiles.”

Sanford Jones was back home. The world was trying to heal after a horrific war, and he found Lost Creek was still an isolated place.

Beyond Lost Creek

“It was a little bit awkward at first being home. It was different from the military world I left. I wanted to do something with myself and I knew that education was the way,” said Jones.

He secured his high school diploma from Robinson High School in Perry County. He then successfully applied to the Eastern Kentucky State College (now Eastern Kentucky University) under the federal GI bill and earned a science degree.

At the University of Kentucky, he not only got a master’s degree in science but met the love of his life.

“At UK’s Student Center one day in the summer of 1954, I saw a group square dancing. I don’t think they do much of that today at UK. I saw a certain girl. I liked what I saw. I introduced myself and she started looking at me. I asked her to dance. We did. I then thought I would never see her again. So I asked her out for a date the next night. She was working on her master’s in elementary education. She accepted.”

On Aug. 18, 1956, Sanford Jones and June Elizabeth Daugherty of Louisville were married at Crescent Hill Methodist Church in Louisville. She had been teaching the last six years at Brandeis Elementary School in Louisville.

After he finished his doctorate at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center in Memphis, the couple moved to Richmond in 1961 where he became a professor at Eastern Kentucky University. For 13 years, he served as chair of the school’s Department of Biological Sciences. He retired June 30, 1992.

They have three children: Sanford Logan Jones Jr., a psychiatrist in Cincinnati; Henry Mason Jones, a teleradiologist in Rancho Mirage, Calif., and Catherine Elizabeth Jones, an architect in Manhattan in New York City.

Sanford’s wife died March 23, 2019. She was almost 91. Besides raising a family, she taught a Sunday school class at a local Methodist church and was active in the League of Women Voters.

“She had a bad fall and fracture. We had about 63 years together. I appreciate all of them,” said Jones.

During their marriage, they visited the island of Capri in Italy, known for its picturesque scenery. That’s where young Jones was stationed for “rest and relaxation” breaks from his combat missions in World War II a world ago.

He says today his life has been “one of wonderful connections.”

In recent years, his namesake son has taken him to World War II museums and reunions. Earlier this year, he was invited to be a panelist at the grand National WWII museum in New Orleans with two other veterans to share stories that highlighted the bravery and humility of veterans in the global conflict that ended 80 years ago.

“I couldn’t turn that down, though I was a little nervous,” he said.

Video of the National WWII Museum’s commemoration ceremony is available on Youtube. The panel discussion begins at about 18 minutes.

Kentucky Lantern is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Kentucky Lantern maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Jamie Lucke for questions: info@kentuckylantern.com.