By David Rotenstein

NKyTribune staff writer

Daniel Woodie wants to get public records from Kenton County and the City of Covington that he believes could clear his name after a Kenton County judge in 2024 granted an interpersonal protective order (also known as an IPO) against him. A Kenton County woman had claimed that Woodie was stalking her.

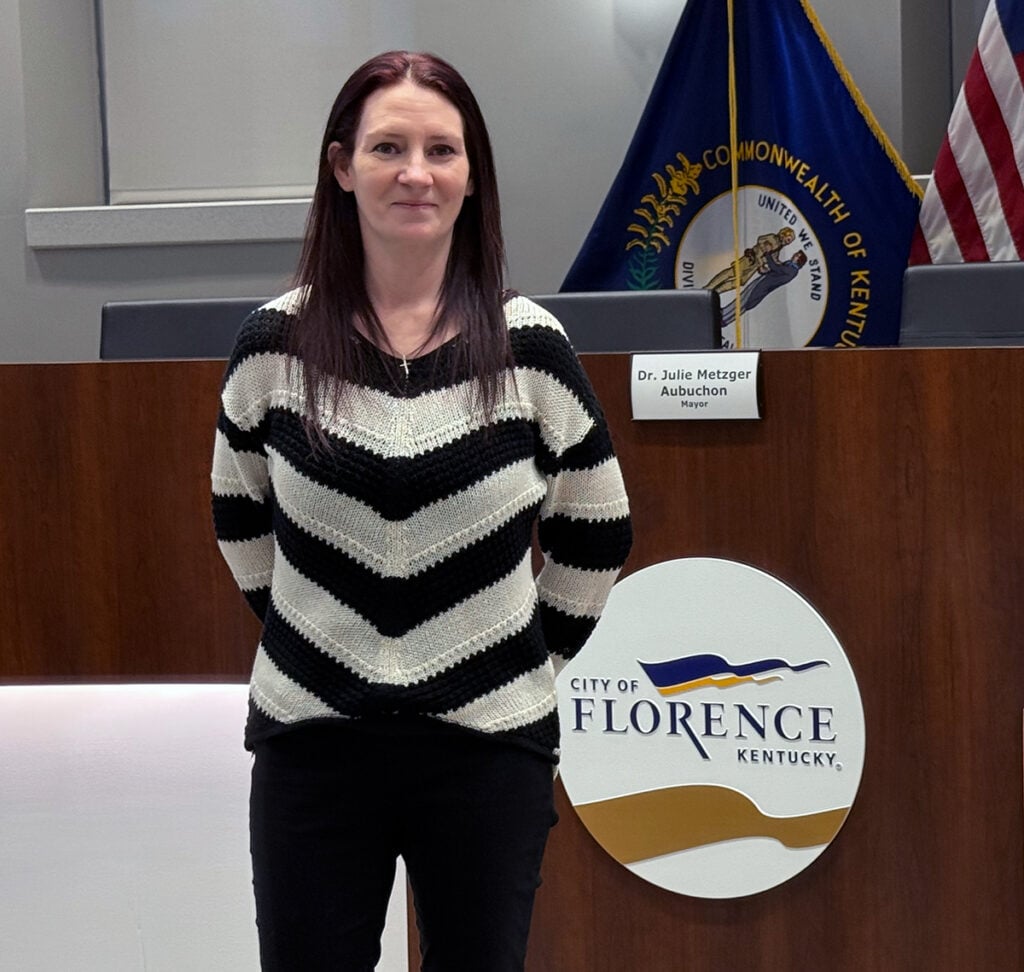

Woodie is a former Kentucky resident who now lives in Cincinnati. Because he doesn’t live in Kentucky, Woodie couldn’t request public records. Instead, he enlisted a childhood friend, Florence city council member Angie Cable, to help him get them.

Cable submitted open records requests to law enforcement agencies in Kenton County. She also used a provision in the Open Records Act authorizing Woodie to submit open records requests on her behalf.

The requests yielded unexpected responses from officials in those jurisdictions because of the type of records requested and because she intended to transfer the records to a third party, Woodie, after receiving them.

What began as a simple request for public records devolved into accusations by Cable that the City of Covington and Kenton County were not complying with the Open Records Act.

Cable’s efforts on behalf of her friend exposed fault lines in Kentucky’s Open Records Act. The episode highlights how Kentucky’s law erects barriers to public records sought by people who don’t live in Kentucky but who, for a wide array of reasons, may need access to Kentucky records.

Accusations led to search for answers

“I started doing open records requests after I had a protective order petition filed against me in order to get records that could help in my defense,” Woodie told the NKyTribune.

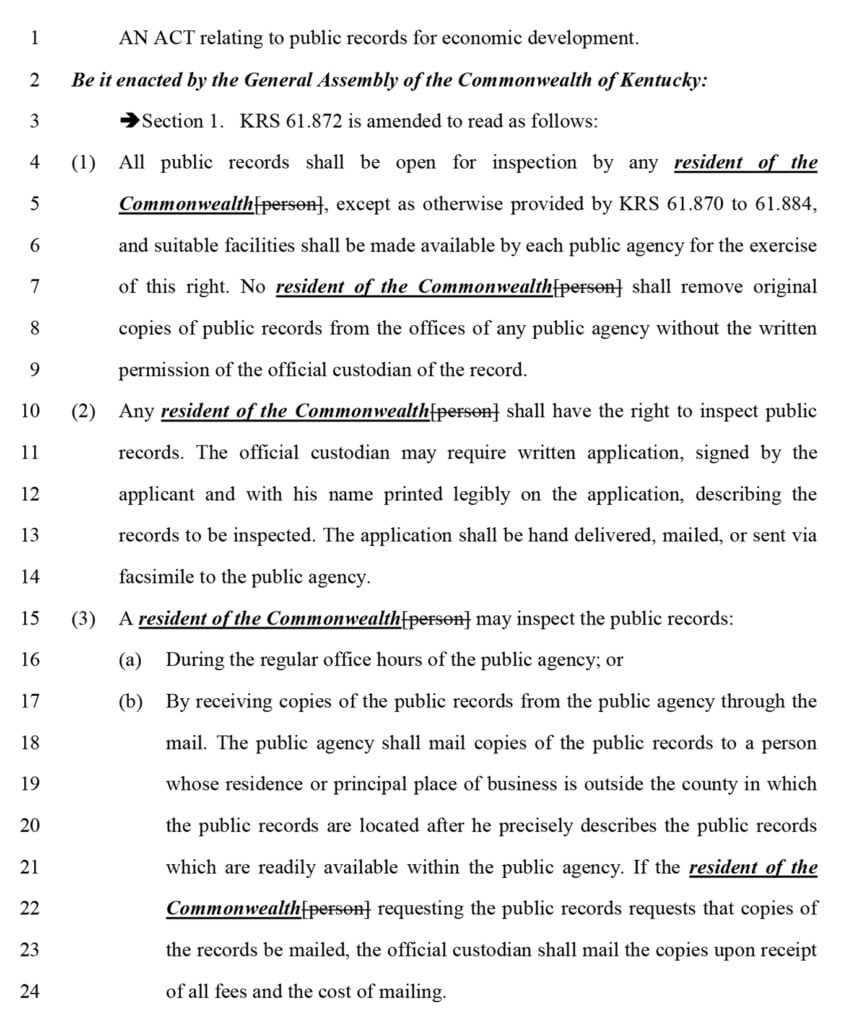

Woodie is technology contractor and part-time Uber driver who does business in Northern Kentucky. He also says that he is a part-time resident. Woodie believed that his initial requests for records in 2024 were covered under Kentucky’s Open Records law. Enacted in 1994, the legislature amended it in 2019 making it more difficult for non-residents to request records. With a few exceptions, only Kentucky residents may file open records requests.

Woodie filed his initial requests citing two parts of Kentucky’s Open Records Act. He claimed that his part-time residence in Northern Kentucky and his employment status met the residency qualifications.

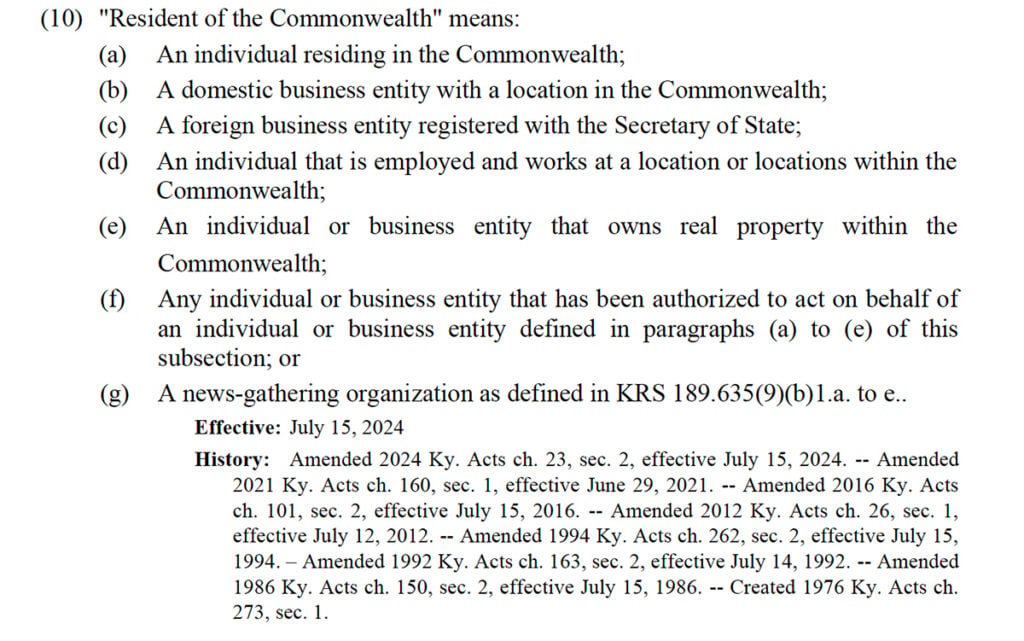

The law has eight categories in its definition of “Resident of the Commonwealth.” Among them are individuals living in Kentucky, businesses incorporated in Kentucky, individuals and businesses owning property in Kentucky and individuals “employed and [working] at a location or locations within the Commonwealth.”

Kenton County denied Woodie’s requests in 2025. According to a June 13, 2025, Kentucky Attorney General’s Office opinion, Woodie’s work ties to Kentucky didn’t qualify him to make open records requests. The decision cited sworn testimony by Woodie that he “‘work[s] from home’ at a location outside Kentucky.” The decision also noted that Woodie’s part-time employment as an Uber driver making short trips into Kentucky didn’t qualify him as a resident.

Unable to get the records he requested, Woodie recruited Cable to act on his behalf. The fact that Woodie was unable to get public records troubled Cable, who was elected to the Florence City Council in 2024.

“I’m a big proponent for transparency,” Cable explained. “That’s what I ran on, transparency and accountability because I feel as though our government doesn’t like to release information unless they’re forced to do so.”

Cable submitted her requests to get Woodie’s records. Instead of getting the files, she received telephone calls from the Covington Police Department and the Kenton County Attorney’s office.

A Covington police detective called Cable to verify that she had authorized Woodie’s request. The Covington detective also implied that Cable might be contributing to the alleged stalking by assisting Woodie in getting the information he requested.

Cable provided the NKyTribune with a recording of the Jan. 23 conversation. “What I’m looking into is whether he’s using open records to stalk this person or not,” the detective told Cable. He added, “But now you’re kind of part of it because you’re the one requesting the records.”

After the phone call, Cable rescinded her authorization and her direct requests.

She later reconsidered the decision to rescind the requests and asked that they be reopened.

“My decision to rescind the request was not made freely or voluntarily. It was made only after direct communication from a law enforcement officer that implied criminal consequences, personal liability, and potential harm associated with pursuing a lawful open records request,” Cable wrote in an email to Assistant Kenton County Attorney Christopher Nordloh. “This communication created a coercive environment and reasonably caused me to fear retaliation or legal repercussions for exercising a protected right under Kentucky’s Open Records Act.”

The Open Records Act does have provisions to withhold and redact sensitive information that would violate personal privacy or certain law enforcement records related to ongoing investigations.

Kentucky Assistant Attorney General James Herrick wrote in an opinion issued Feb. 2, 2026, that Kenton County didn’t violate the Open Records Act “when it denied eight requests for public records because the requester is not a resident of the Commonwealth.”

“The Kentucky Attorney General has reviewed a voluminous record including recordings of phone calls between Ms. Cable and public officials and has rejected claims that Ms. Cable’s revocation was invalid,” Nordloh replied to a request for comment on Cable’s allegations. “The AG has held three times now, including again today, that Kenton County did not Violate the Open Records Act by denying this pair’s serial requests for records.”

Nordloh also wrote that he has not had any communications with the Covington law enforcement officer mentioned in Cable’s email. “I was not a party to the phone call between the officer and Ms. Cable and certainly cannot speculate how it might have made her feel.”

Covington City Solicitor Frank Schultz referred all questions about the Open Records Act requests to the city’s Director of External Affairs, Sebastian Torres.

“The Covington Police Department maintains that the statements of the involved Detective were appropriate in light of an underlying investigation regarding alleged attempts by an individual to seek contact with a victim despite the presence of an active protective order being in place,” Torres replied to the NKyTribune’s request for comment. “As of the publication of this statement, the Covington Police Department has not received an official complaint from the individual who made these erroneous allegations.”

The law creates barriers to information

According to former Kentucky Assistant Attorney General Amye Bensenhaver, a founder and board member of the Kentucky Open Government Coalition, Kentucky law doesn’t prohibit Kentucky residents from sharing records received through Open Records Act requests.

“There is no prohibition on sharing the records that you have acquired with a third party,” Bensenhaver told the NKyTribune. “Once they release them, they’re public records, they’re public to everyone, not just the person who acquired them.”

Bensenhaver finds the Kentucky residency requirement imposed by 2019 revision to the law deeply problematic. It erects unnecessary and easily circumvented barriers to public records.

Bensenhaver explained that one reason for the changes had to do with reducing the burdens placed on local governments fulfilling lots of requests. “If somebody out of state wants a record from Kentucky, all they have to do is find somebody in Kentucky to make the request for them,” Bensenhaver said.

Kentucky is one of a small number of states that limit public records requests to residents. Tennessee is another one of them and one of the most restrictive. The state’s Public Records Act limits access to citizens of Tennessee. Unlike Kentucky’s law, Tennessee law allows government agencies to request identification to prove residency.

Virginia’s Freedom of Information Act also restricts access to public records to residents. There are exceptions for journalists, unlike Tennessee’s law which technically bars out-of-state journalists from making requests.

To get around the laws, cottage industries have cropped up in places like Tennessee where brokers can charge people from out-of-state for public records,” Bensenhaver explained.

Students enrolled in out-of-state universities also find themselves caught up in Kentucky’s restrictive open records law. Bensenhaver described initiating open records act requests — pro bono — for students based in California researching Kentucky topics. “The group I work with has done it several times,” she said.

When University of Maryland urban studies and planning professor Ariel Bierbaum needed geographic information systems (GIS) data from Jefferson County in 2024, she got as far as the open request form posted on the county’s school district website. She hit a roadblock after reaching the residency certification at the bottom of the form.

“I came to that and I said I’m not going to lie that I live in Kentucky because I don’t” Bierbaum said from her home in Silver Spring, Maryland. “It sort of stalled my process for a little bit of time.”

To get around the residency requirement, Bierbaum reached out to people she knew in Kentucky, including friends and colleagues.

“There’s some journalists that I was following on social media,” Bierbaum said. “So I sent one of those journalists a cold email and asked them if they would be willing to submit the records request and share with me the data that they received.”

Bierbaum eventually got the data after what she sees as an unnecessary delay. She got the information she needed to complete her study and it only added an additional few weeks to her work.

“I think in my case I was lucky,” she said. “I couldn’t really understand the justification for something like that, outside of being kind of obstructionist.”

Bensenhaver agrees.

“They go to infinite lengths to try to withhold a record in Kentucky when the law, as the courts have said, exhibits a bias favoring disclosure,” the attorney said. “But instead of exercising that bias in favor of disclosure, they go to infinite lengths to try to deny access.”