By Paul A. Tenkotte, PhD

Special to NKyTribune

In the 21st Century, we celebrate Veterans Day as if the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month marking the armistice ending World War I was somehow a “fait accompli,” that is, destined to be a national holiday.

However, its origins were far from incontestable. Rather, they were marked by political and ethical considerations. The United States in the 1920s was still a nation in search of itself. Its isolationist tendencies had been dragged into an international conflict for which Americans had made many sacrifices. After the hostilities ended, separate voices argued for a holiday dedicated to peace, while others wanted a display of the nation’s military prowess.

As World War I ended, Democratic President Woodrow Wilson advocated for his plan for a League of Nations (LON), for which he won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1919. Considered the world’s first international organization dedicated to collective security and peace, the LON was founded at the Paris Peace Conference in January 1920. Despite Wilson’s efforts, the US Senate voted against joining the LON, concerned that it would threaten the constitutional power of the US Congress to declare war.

The Armistice of 1918 produced a rather spontaneous celebration in the Cincinnati and Northern Kentucky region. Church bells rang in jubilation and impromptu parades arose. Revelers threw so much confetti in Cincinnati, in fact, that it took an entire day to clean it up.

In 1919 Ohio Governor James M. Cox (1870–1957), a Democrat, declared Armistice Day a legal holiday in the state. Interestingly, Cox would run for president of the United States in 1920, with Franklin D. Roosevelt as his running mate. Republican Warren G. Harding, also of Ohio, defeated the Cox/Roosevelt ticket in a landslide.

In Cincinnati, the 1919 Armistice Day celebrations drew thousands of participants from 150 organizations to Music Hall. Across the street at Washington Park, plans included soldiers from Fort Thomas (Kentucky) firing volleys from a cannon “promptly at 11 a.m.,” followed by the explosion of bombs. Then, in Music Hall, a “chorus of 1,000 girls” was to lead “community singing” (“Legal Holiday Is Ruling,” “Cincinnati Enquirer,” November 6, 1919, p. 10).

The following year, in 1920, Kenton County (Kentucky) officials commemorated deceased World War I service personnel. A plaque, “containing 129 names of dead soldiers, sailors and marines” from the county was dedicated at Covington City Hall. Members of the American Legion and the Boy Scouts attended (“Unveil Memorial Tablet,” “Cincinnati Post,” November 8, 1920, p. 1).

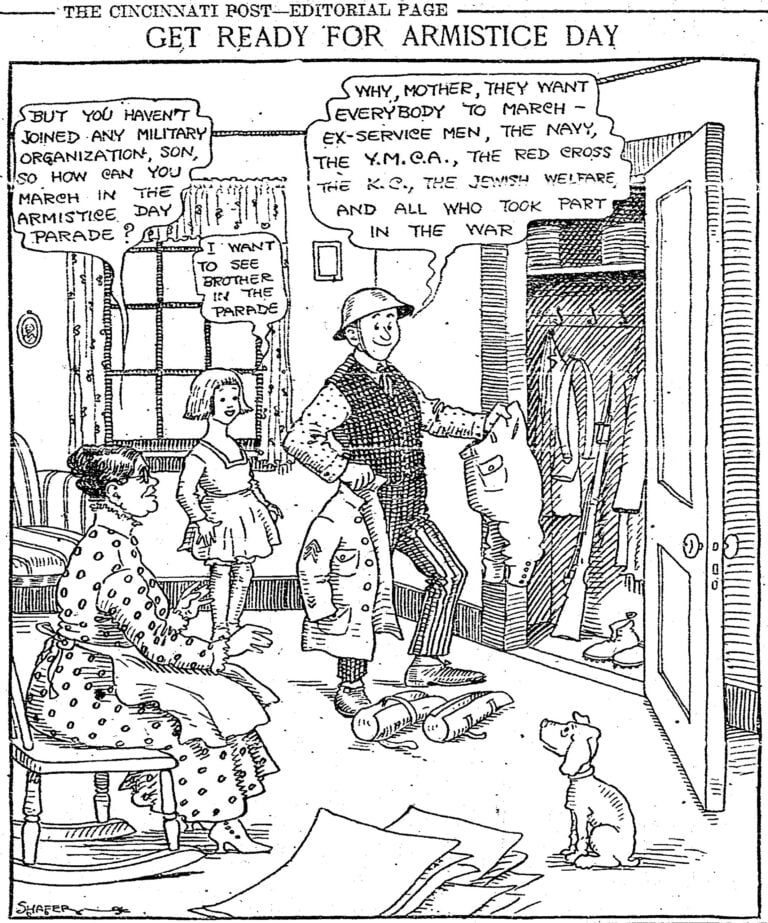

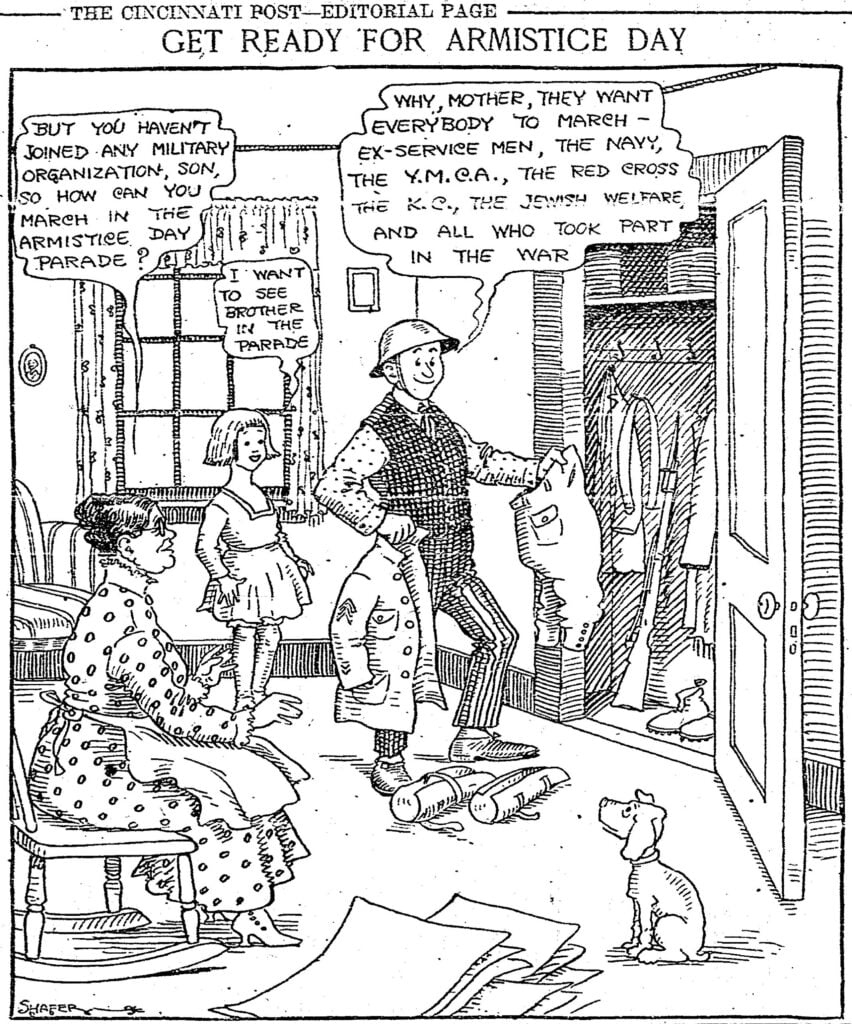

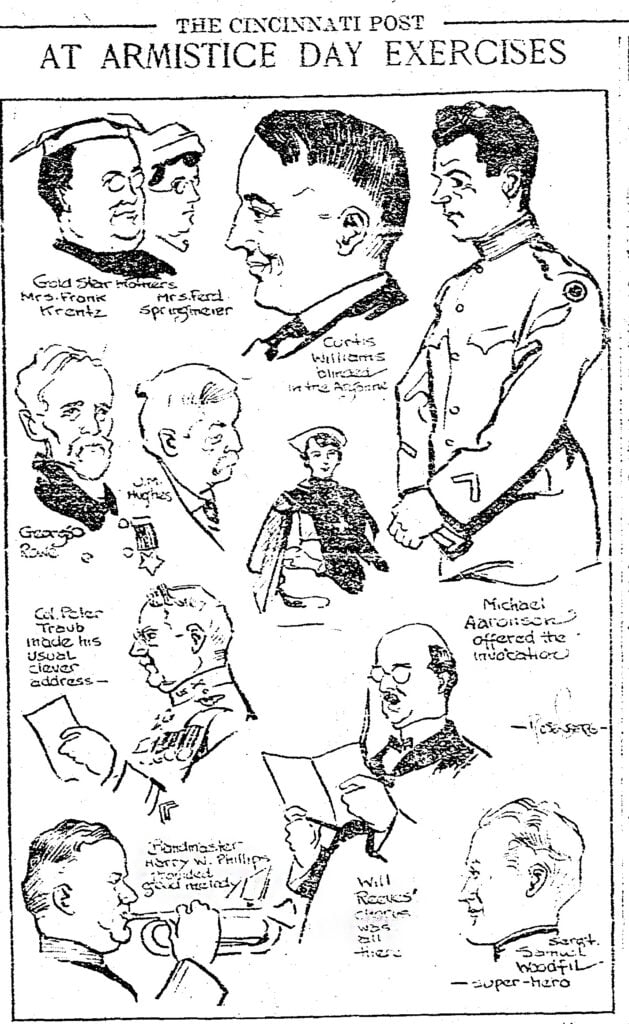

In neighboring Cincinnati, Mayor John Galvin asked residents to respectfully observe Armistice Day 1920. “I ask the people of this city,” he wrote, “to celebrate Armistice Day with rejoicing for the blessings it brought and with prayerful consideration for the losses sustained.” The “Cincinnati Post” celebrated the inclusion of all participants in the celebration — not merely veterans — with an editorial cartoon on November 9th. The 1920 observance featured a parade with Gold Star mothers, a gathering at Emery Auditorium, and a call for all city schoolchildren and residents to observe one minute of silence at 11 AM (“Peace Prayers: Galvin Issues Armistice Day Proclamation,” “Cincinnati Post,” November 8, 1920, p. 9; “Peace Memories: Armistice Day Recalls That One of Two Years Ago,” “Cincinnati Post,” November 11, 1920, p. 1; “ ‘Our Country,’ ” “Cincinnati Post,” November 12, 1920, p. 3).

In 1924 the War Department, with the encouragement of President Coolidge, designated September 12th as “National Defense Day” (NDD). National Defense Day proved to be a controversial topic, particularly since its official launch in September 1924 was followed only weeks later by a presidential election. The editorial staff of the Democrat-leaning “Cincinnati Post,” while admitting that the idea had “some merit,” nonetheless questioned its timing. Further, it assailed the fact that it was directed by the War Department, expressing a constitutional concern that “When the War Department assumes command of the civilian body in time of peace we are turning our theory of government upside down” (“A Real Defense Test,” “Cincinnati Post,” July 31, 1924, p. 4.)

What exactly was the National Defense Day? In essence, it was publicized as an annual test of US preparedness for war. Programs included a call for civilians to enlist in the armed forces for one day, for which they would receive a commemorative button. There would be military parades nationwide. People were encouraged to wear red, white, and blue, and homes and businesses to display the US flag. And in the Cincinnati area, “Every enrolled Red Cross nurse” was “asked to report in person, by letter or telegram on that day at a designated point, to show how quickly they could be mobilized” (“Mobilization Test,” “Cincinnati Enquirer,” September 4, 1924, p. 3; “Proclamation Is Issued by Mayor,” “Cincinnati Enquirer,” August 30, 1924, p. 16).

Also in September 1924, the NDD — in cooperation with the Bell Telephone System nationwide— inaugurated a National Defense Test. For the first time, radio stations nationwide were connected via “long distance lines through special switching of circuits so that a single chain of direct communication” was “established between Washington and the various stations involved.” This prototype of a synchronized alert system featured a simulcast of addresses by War Department officials, among them General Pershing. It included 17 radio stations nationwide. Among them were WLW of Cincinnati and KDKA of Pittsburgh (“Stations to be Linked for Talk on Defense When War Chiefs Speak September 12,” “Cincinnati Enquirer,” September 7, 1924, p. 110).

The American Legion was a firm supporter of National Defense Day. For example, Garland W. Powell, Director of the Americanism Commission of the Legion, proclaimed that “The war [WWI] taught us the great necessity of being prepared in case of emergency … The nation for its own salvation should know its strength, not only in industry, but in man power, at all times.” Further, the American Legion viewed NDD as a way to promote the passage of a universal draft bill. Considering the fact that the compulsory military drafts of President Wilson were far from popular, it is not surprising that NDD itself quickly became controversial nationwide (Legion Backs Defense,” “Cincinnati Enquirer,” August 2, 1924, p. 7).

The establishment of National Defense Day aroused the suspicions of some Americans concerned about the growing influence of militarization at the expense of peace. For instance, the Woman’s City Club of Cincinnati sponsored the organization of a Cincinnati Peace League in Fall 1924 “to study the causes of war and to foster in the community the desire and will for peace.” The new Peace League was careful, however, to distance itself from “pacifism, bolshevism,” and other movements “with which peace has been confused” (“Pacifism Hit as Peace Is Urged,” “Cincinnati Post,” October 10, 1924, p. 2).

The 1924 Armistice Day observances in Washington, DC included Republican President Calvin Coolidge laying a wreath on the tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Arlington Cemetery. The “Cincinnati Post” noted that President Coolidge was reluctant to declare Armistice Day as a national holiday, firmly believing that such a decision was a constitutional prerogative of the Congress and that he had no authority to declare a holiday for federal workers (“Armistice Day Homage Paid,” “Cincinnati Post,” November 11, 1924, p. 14).

By Spring 1925 the War Department expressed its desire to move National Defense Day to Armistice Day. President Coolidge, however, disapproved, and the War Department instead chose to celebrate NDD on July 4th of 1925. Cincinnati observed the day with a parade and other events. Nationwide, it was expected that as many as “1,000,000 persons” were planning to “respond to the War Department’s invitation to become ‘citizen volunteers’ for the day and to take part in the demonstration for organized peace as the basis for immediate mobilization should emergency arise” (“Strength Test on Program,” “Cincinnati Post,” July 2, 1925, p. 13).

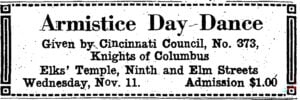

The co-celebration of July 4th and National Defense Day on Independence Day did not seem to dampen Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky’s Armistice Day observations in November 1925. Cincinnati held an Armistice Day parade. Covington schools were closed, as Armistice Day was a legal holiday in Kentucky. Covington businesses were asked to close for an hour from 10-11 a.m. At 10 a.m., the Norman-Barnes Post of the American Legion sponsored a public commemoration service at the Liberty Theater in Covington. There, the audience stood “in silence for a minute as a tribute to the memory of the soldiers of the World War” (“Armistice Day Route Given,” “Cincinnati Post,” November 9, 1925, p. 5; “Schools Close: Armistice Day Legal Holiday in Kentucky,” “Kentucky Post,” November 10, 1925, p. 1; “Armistice Day in Covington: Legion to Hold Public Service at Liberty Theater,” “Kentucky Post,” November 10, 1925, p. 1).

Thirteen years later, in May 1938, the US Congress finally established Armistice Day as a legal holiday. In June 1954 Congress officially renamed Armistice Day as Veterans Day.

Paul A. Tenkotte, PhD is Editor of the “Our Rich History” weekly series and Professor of History at Northern Kentucky University (NKU). To browse ten years of past columns, see: https://nkytribune.com/category/living/our-rich-history/. Tenkotte also serves as Director of the ORVILLE Project (Ohio River Valley Innovation Library and Learning Engagement). For more information see https://orvillelearning.org/. He can be contacted at tenkottep@nku.edu.