In a state where basketball is a religion, a small, mountain school is accused of heresy – disturbing the hierarchy of Kentucky high school sports. Fined, sanctioned and harassed for its transfer students – many of whom are urban and black – the Cordia School has a history of coming from behind. But this is about more than basketball, says Coach Rodrick Rhodes, a former UK star.

By Willie Davis

Special to NKyTribune

One of the smallest schools in Kentucky—the Cordia School—nestled deep in an isolated part of the Appalachian Mountains, is known for its fights.

“Every few years, [the school board] try to consolidate us, so we have to fight against that,” says Alice Whitaker, head of Lotts Creek Community School, which owns the Cordia School buidling and helps support it. It has been in a vicious, decades-long fight with the coal corporations that want to strip-mine the surrounding mountains.

“There was a war back then,” Whitaker says of the coal fights in the ’60s and ’70s. “You could set out here and hear the gunshots.”

She tells of her aunt Alice Slone, the founder of the Cordia School. “Aunt Alice called that mountain ‘Adam,’” she says, pointing to a tall, yellow mountain towering over the school.

“They come in with bulldozers to strip it. She broke up and called Woodrow Guthrie down the road and said, ‘They’re trying to strip-mine Adam.’ Within a half-hour, there were 20 men out there with guns. They went away, and haven’t come back yet.”

What the school has never been known for, however, is sports. That changed three years ago when former University of Kentucky Wildcat star Rodrick Rhodes shocked the basketball world by agreeing to become Cordia’s head coach. He’s turned tiny, mountain-bound Cordia into a strong basketball school. Other schools have started to notice, and they’re not happy.

First, the Kentucky High School Athletics Association banned certain students from playing. They claim that Rhodes and Cordia are illegally recruiting students to play for them. They can think of no other reason why students from New York, Canada, Mali and all over would want to come to East Kentucky to play basketball in Cordia. The cultural difference is too large, and Cordia is not a basketball school.

At first blush, nothing in this story makes sense. New Jersey native Rodrick Rhodes—who left Kentucky on bad terms the first time—isn’t supposed to be thriving in the hollows of Appalachia. Cordia, known for its activism and its environmentalism, is not supposed to be good at basketball. What does make sense—in fact, what seems inevitable—is that Cordia is fighting.

“I’m praying they don’t give us a slap on the wrist,” Whitaker says with a laugh. She knows Cordia will be outspent, she says, but she hopes they don’t go too easy on them. “I want them to lower the boom. We can fight that.”

Three months after she says this, the KHSAA complies, levying unprecedented penalties on the team and the school itself. They not only banned Cordia from playing any games in the 2014-15 season, any games in the 2015-16 postseason, but also fined the school almost $26,000. The fine alone could cripple a large school, but it threatens Cordia’s existence going forward.

“I wasn’t wanting that much punishment,” Whitaker says, after the ruling had been laid out. “I did want enough so I could appeal it.”

Cordia continues its fight with KHSAA, and it can get even more acrimonious. But this is not a story about the intricacies of high school basketball. This is about the well-being of children, the future of Appalachia, and whether or not the Commonwealth of Kentucky can stop making the same mistakes it has made over and over.

Kentucky takes the short money

In 1976, the National Basketball Association was looking to expand. Having won a decisive victory against the upstart American Basketball Association, the league looked to absorb the most profitable teams from its prostrate rival. In short order, they took the Indiana Pacers, the Denver Nuggets, the San Antonio Spurs and the New York Nets. That left only two remaining ABA teams: the Kentucky Colonels and the Spirits of St. Louis. The NBA offered both of the ABA teams a $3 million buyout.

The Kentucky Colonels were a strong organization, with dedicated fans, high attendance and a vicious—and profitable—rivalry with the Indiana Pacers. They made a strong case for joining the NBA if they held out. On the other hand, their owner—future Governor John Y. Brown—had already alienated many Colonel fans by selling off former Kentucky Wildcat star Dan Issel as well as the team’s other more profitable assets to rival teams. The organization also had the example of the Virginia Squires, an ABA team that folded months before without recouping a dime from the NBA. In the end, the Kentucky Colonels decided to take the money.

The Spirits of St. Louis, however, crafted their own deal. They took a smaller payout upfront ($2.2 million instead of $3 million) and 7 percent of future TV revenue of any of the four ABA teams the NBA absorbed. This wound up netting the owners of the team upwards of $300 million, with their revenue increasing constantly, until last year when the NBA bought out their contract for, among other concessions, $500 million upfront. The deal is often called the greatest in sports history.

Of course, it’s as useful to point out the winner of a 39-year-old business deal as it is to gamble on last year’s Derby. Nevertheless, the disparity—$3 million compared to nearly a billion—is hard to ignore. For people who study Kentucky politics, it’s also an eerily familiar pattern: The leaders sell off their best assets, devalue the organization as a whole, then strike a frontloaded, self-serving deal that gets worse with every passing year.

In Kentucky, basketball is king: beyond coal, culture, religion and politics. In basketball and in government alike, in 1976 and today, Kentucky has most often gambled against itself and taken the short money.

The former future of the Kentucky Wildcats

This is not Rodrick Rhodes’ first fight.

For a few months, all of Kentucky’s hopes were invested in Rhodes. When the superstar 6-foot-6-inch forward from Jersey City committed to become a Kentucky Wildcat in 1992, many Kentucky fans assumed a title was inevitable. Coach Rick Pitino had just taken an undermanned Wildcat team to an Elite Eight, where they came a heartbreaking last-second shot from upending powerhouse Duke. Rhodes was the all-world talent Kentucky’s devoted fan-base demanded. Even without the Internet to whip the Big Blue Nation into a frenzy—as it would later with similarly touted freshmen John Wall and Anthony Davis—the fans couldn’t wait to ring in the Rhodes dynasty.

At UK, he was a very good player. That’s the last thing many fans remember when discussing his career. He scored over 1,200 points in three years, received All Southeast Conference honors each of the seasons he played at UK and was drafted by the Houston Rockets in the first round. By most standards, that is a fantastic collegiate career. Rhodes, however, was never held to most standards. Many UK fans remember his second-ever game, where he dominated Georgia Tech, scoring 27 points and putting the rest of the NCAA on notice. Typically, they only bring up that game to ask why he didn’t do it again. If he could be such a monster in his second game and never again, was he regressing?

More often, fans remember one of his final games, the SEC championship against Arkansas. Arkansas, No. 5 in the nation and defending national champions, had Kentucky down 19 points. Rhodes was struggling, having failed to score in the second half. Still, thanks to the Wildcats’ bevy of other stars, Kentucky clawed back into the contest late. With five seconds left and the game tied, Kentucky Freshman Antoine Walker stole an Arkansas pass and called a timeout. Against all odds, despite getting outplayed, Kentucky had one last play to steal an SEC Championship.

Coach Pitino called Rhodes’s number. Rhodes drove into the teeth of the defense, and when Arkansas collapsed on him, he dropped a perfect pass to power forward Walter McCarty for a game-winning dunk. Except the basket didn’t count. The refs said that Arkansas swiped Rhodes’s hand before he made the pass with 1.3 seconds left. That meant Rhodes, a 78 percent free-throw shooter, had two chances to be the hero that Kentucky had once believed him to be. He missed the first free throw, and then, with his teammates praying and refusing to look at the rim, he missed the second.

During overtime, Pitino benched Rhodes, and the cameras showed him on the bench, openly crying. Kentucky went down nine in the overtime before making one last improbable run to win the game. When Kentucky went ahead for the first time in the game, with only a few seconds left, the announcer said “Rodrick Rhodes is the happiest man in the Atlanta-Dome.” After a pause, the color commentator replied, “He doesn’t look it.” Because even as they were celebrating Kentucky’s SEC championship, Rhodes’s cheeks looked wet with tears. Kentucky was triumphant, but Rhodes was again out of step.

A few games later, Kentucky flamed out against North Carolina in the Sweet Sixteen. Not long after, Rhodes announced he was transferring to Southern California. Rhodes was done with Kentucky, and Kentucky, armed with another stud freshman in Ron Mercer, was done with Rhodes. Rumors abounded that Pitino, wanting to keep Mercer happy, forced Rhodes out. Rhodes denied that, saying the transfer was his idea. “I won out,” Rhodes said to ESPN at the time.

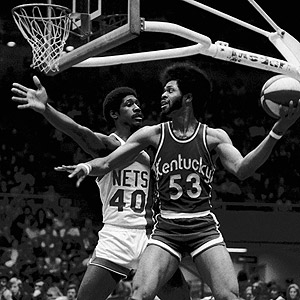

The Cordia High School Lions (white jerseys) take on the much larger consolidated school, Knott Central High, in 2011, during Rhodes’ first year as head coach. If Rhodes is cheating, he says, he ought to be winning a lot more games. His career record at Cordia is 61 wins and 42 losses.

Today, he tells a different story. “Everyone knows I didn’t want to leave Kentucky. Every single Kentucky fan knows what happened with me and Coach P. and Ron Mercer. Kentucky fans are smart enough to think they can out-coach [current UK head coach John] Calipari. If you’re smart enough to be a Kentucky fan, you’re smart enough to know I never wanted to leave Kentucky.”

As he sat out his transfer year, Kentucky won the National Championship in Rhodes’s native Northern New Jersey. After college, Rhodes went to three NBA cities, then the international leagues, and then worked as an assistant coach at the college level. But after several years, he lost his passion for assistant coaching. “I got burnt out on travelling, recruiting kids, losing out to bigger schools,” Rhodes says. “I put something on Facebook saying I’d be interested in coaching high school. The dumber schools put something right there on my Facebook wall, but the smart ones hit my inbox. Cordia sent something to my inbox.”

“Rodrick was the initiator,” says Whitaker, head of the nonprofit that supports the Cordia School. “He wanted to come back this way and be closer to his daughter in Virginia. He applied and we all had our jaws drop.”

Within three years, Rhodes has turned tiny Cordia into a successful basketball school. In doing so, he’s won a lot of fans and made a lot of powerful enemies.

This particular fight is about the students Rhodes has brought to East Kentucky. They are usually students from rough, often violent homes, and they see Cordia as a sort of asylum. When the state athletic association banned two Canadian students from playing, the students sued the organization to restore their eligibility.

It bears mentioning that the out of-town students that come to play for Rhodes are largely black and Cordia’s Knott County is overwhelmingly white, a detail that has been noticed by approximately everybody.

Crashing the dance

Most people think Rhodes’s native Jersey City is wildly different from Cordia, but Rhodes disagrees.

“Honestly speaking, I have more things in common with this area of East Kentucky than you imagine,” he says. “[There are] a lot of similarities to inner cities. A lot of love. And drug problems. People who don’t have a lot.” He says his players’ experiences remind him a lot of his own time in high school. “I went to a small high school….We didn’t play in a gym. We played in a bingo hall. We literally had to put up the bingo tables so that they could play bingo on Saturday.”

The differences, however, are very real. “Culturally, it’s very different,” Rhodes says. “[In Kentucky] it’s not frowned upon to give a child a gun.”

While basketball is revered in both places, the passion Kentuckians have for their favorite sport can surprise even experts. “Speaking about high school basketball?” Rhodes says. “It’s been very intense. It’s been very…” He laughs and then reconsiders. “I’m going to stick with intense.”

That intensity has its advantages for a coach, but it also ensures that everything he does is under a microscope, and there is always someone trying to bring him down. “I’m baffled by a lot of the attention we get from KHSAA,” Rhodes says. “It’s not warranted. It’s other schools jealous of the semi-success we’re having.”

For Rhodes, the matter is simple. “Kids are wanting to go to Cordia. Their families want them to go…Big schools have transfer students. I don’t even know who won state this year, but I guarantee there were transfer students. The team they beat in the championship had transfer students. The teams those teams beat in the Final Four had transfer students. Every team those teams played in the Sweet Sixteen had transfer students. Why are we being picked on?”

The answer, according to Alice Whitaker, is simple: The KHSAA doesn’t like Cordia or Rodrick Rhodes. “They don’t want us to win,” she says. “KHSAA is a Nazi organization. They have too much power over kids.” She says the rules not only hurt kids, but they are arbitrarily enforced. “One of the Canadian kids was ruled ineligible [by KHSAA]. The same people ruled his brother eligible [to play for a different school].”

Whitaker was accused of buying a plane ticket for a basketball player to send him home early. “They said I bought it,” she said. “Which I did. I do. I do it for non-athletes all the time. That’s not a bit unusual. He was just homesick.” This, she insists is a service she offers to all of her students, basketball players or not. Moreover, she uses her money, not the school’s, as the KHSAA alleged. “You can’t punish Cordia for what Alice Whitaker…does.” Similarly, she laughs off the accusation that she provides free housing for the basketball players. “Housing is for everybody…We’ve had dorms from the very start.”

She insists that the enmity stems from their personal feelings toward Rhodes and “the fact that he came in with a flair…with the big front page story in the paper.” Whitaker insists she’s not surprised with how nasty this fight has become. “We had outside students in other sports. It’s never been a problem—but I expect it.”

Of course, there is a simpler, cruder possibility as to why Cordia is being singled out. “I don’t know if there’s ever been a minority coach who won the 14th Region with a mostly minority team,” Rhodes says. “I don’t know, but I don’t think so.” Rhodes doesn’t say for sure that racism is behind the KHSAA’s decisions, but some of the rancor Cordia has faced is undeniably bigoted. “We had ugly stuff. People burning a Canadian flag. Holding a noose. Saying they’re going to ‘get the n****r.’”

Rhodes emphasizes that “Eastern Kentucky has been great” to him and his players. Still, he laughs off questions about whether his players have adjusted to the Appalachian Mountain culture. “I like to turn the table. If you take a student from Eastern Kentucky and put him in New York, and he has to deal with what these kids have to deal with—from adults—how many of them would be able to take it? I don’t know if I could do that.”

While Rhodes ultimately claims ignorance as to the KHSAA’s motives, he’s quick to bring the subject back to basketball. “I don’t know if it’s racially motivated,” Rhodes says. “Cordia has never been invited to the dance. Now we’re crashing the dance. You think people would like it?”

Bigger than basketball

Because basketball takes up so much of the oxygen in the area, it’s easy to forget that this struggle is ultimately not about who wins more games. It is about the welfare of the students. The kids who travel to Cordia to play for Rhodes, “come from really horrible neighborhoods,” Whitaker says. “One kid from Canada was shot.”

That alone may explain why the students and their parents would want them to play in the relatively quiet mountains of Eastern Kentucky. Still, it is a jarring cultural adjustment that the students have to make. “One kid was scared of trees,” Whitaker said. “He said people could hide in them.” Still, once they get to Kentucky, “[T]hey have been welcomed, loved. They don’t want to go home.”

Cordia School, on Lotts Creek in Knott County, has a history of helping disadvantaged students. Its quiet, rural setting is a stark contrast to the violence some of the school’s out-of-state and international students experience at home, Rhodes said.

She tells the story of a 14-year-old student from Mali, recently transferred to Cordia. “He grew up in a war zone and saw people macheteed to death.” He doesn’t speak English, so he is learning by having the first-graders read to him. He in turn teaches them French by reading to them.

For Whitaker, the KHSAA battle has higher stakes than basketball. “They’re scared to go home. Here they’re totally, totally comfortable, but they really don’t want to go home.” For her, the biggest benefit is changing the trajectory of these kids’ lives. “People are getting college scholarships.” She points to a small gym. “We had as many as 40 coaches from [NCAA Division I] schools here at this gym.”

“Forget the scholarships,” Rhodes says. “We’re saving these kids’ lives. Two of the kids have been shot where they were from…You can’t walk to school without being recruited to a gang. Who wants that? It’s not about basketball.”

The KHSAA can claim that they are not making the students go home, only preventing them from playing basketball. Still, that doesn’t answer Whitaker and Rhodes’ question about why wealthy, mostly white prep schools from Louisville, Lexington and the Cincinnati suburbs can bring in transfer students from across district and state lines without scrutiny.

Rhodes laughs at the idea that he’s cheating. With one exception, he says, the students he’s bringing aren’t basketball prodigies. “Our players aren’t great players. They’re fragile, fractured kids. If they’re so great, these teams wouldn’t let them go. I’m not getting McDonald’s All Americans. If I was, my records would be a lot better. We’re not getting great basketball players. We’re getting black kids, so people assume they’re phenomenal.” He laughs. “If I was cheating, f*** it, I’m going to get a stud…But this isn’t about basketball. I promise you, it’s so much bigger than that.”

As the fight was heading to court, it took another unpredictable twist. Three and a half months after the KHSAA levied the unprecedented penalties against Cordia, the KHSAA Control Board reversed many of the sanctions against the school. Although the board upheld 17 out of 27 of the convictions and maintained both the $26,000 fine and the two-year post-season ban, they modified the biggest ban. Cordia was allowed to play 15 games of their 2014 season, which was seen as an important victory.

Whitaker, however, was not satisfied. “The real story is KHSAA,” she said. “If there was some person with enough balls, they’d expose them.” She sees the KHSAA reducing their fine as an indication that they lack confidence in their own findings. “We fight it,” she said. “KHSAA didn’t have that experience before. People who use their God-given right to fight.”

The case is now in the district court. Whitaker feels confident in the ruling because she “can’t comprehend how [KHSAA’s complaints] could not be thrown out.”

Wherever the fight goes from here, the students are hanging in the balance. While the case can get buried into the minutia of the rules, that doesn’t change the circumstances of the students’ lives. If the KHSAA is right, then Cordia bent the rules in order to win a few more games. If Cordia is right, then they’ve pursued legal means to bring kids from some of the most dangerous places in the world to a safe environment, changing their lives in the process. It’s possible that Kentucky can better serve itself by not getting caught up in the short-term, looking at the big picture and making the long investment.

Willie Davis, a writer and teacher from Whitesburg whose work has appeared in The Guardian, The Kenyon Review and on WMMT radio, wrote this column for The Daily Yonder, where it first appeared. It is reprinted with permission.