By Vicki Prichard

NKyTribune contributor

Marsha Karagheusian’s art has always dealt with loss and longing, but only recently has a broader audience become aware of the ache at the marrow of her work. It’s an acknowledgement that has been a long time coming for this granddaughter of four Armenians who survived the world’s first genocide.

April 24 marks the centenary of the Armenian genocide, when nearly 1.5 million Armenians were killed by the Ottoman Empire, atrocities that the Turkish government acknowledged but maintained were casualties of war, denying a systemic plan to annihilate the Armenian people.

But earlier this month, Pope Francis described the 1915 slaughter of Armenians by the Ottoman Turks as the first genocide of the 20th century. Days later, The European Parliament adopted a resolution Wednesday commemorating the centennial of the Armenian genocide and urged Turkey to recognize that event.

On the eve of a 100th anniversary, the Pope’s acknowledgement, and the very public awareness that has come in its wake, punctuates a century of Armenian efforts to condemn the genocide.

For Karagheusian, who lives in Fort Mitchell, and is a professor of art and education at Xavier University in Cincinnati, her art has long been an insistent voice, demanding awareness, understanding and condemnation of the genocide. Now, just days before the anniversary of the genocide, her artistic indictment of those atrocities was presented at the opening exhibit Flight, at Covington Arts, 2 West Pike Street in Covington. The exhibit runs through May 29.

“I was brought up knowing that I was an Armenian American, and felt intimately related to the culture from an early age,” said Karagheusian. “I would mostly hear the Armenian language being spoken in my home. My maternal grandmother, who lived upstairs from us, taught me how to read and write in Armenian, an Indo-European language all it’s own. My close relationship to all four grandparents, who survived the genocide, shaped me into the person I am today.”

Saad Ghosn, curator of the exhibit, is no stranger to art as a means of political and social expression. Founder of the Save Our Souls art event in Cincinnati, Ghosn said the event uses art as a vehicle for peace and justice.

“It’s really how your art becomes your voice for what you believe in – for what you go through – how you reflect on society,” said Ghosn. “I started SOS in 2003, right at the beginning of the Iraqi War. I felt artists were kind of isolated when they have to speak about their values and beliefs, because society wants more of a commodity than something else.”

Ghosn says Karagheusian’s work speaks to history in flight, carrying the experience of the past into the future, reflecting on the cycle of life of the Armenians.

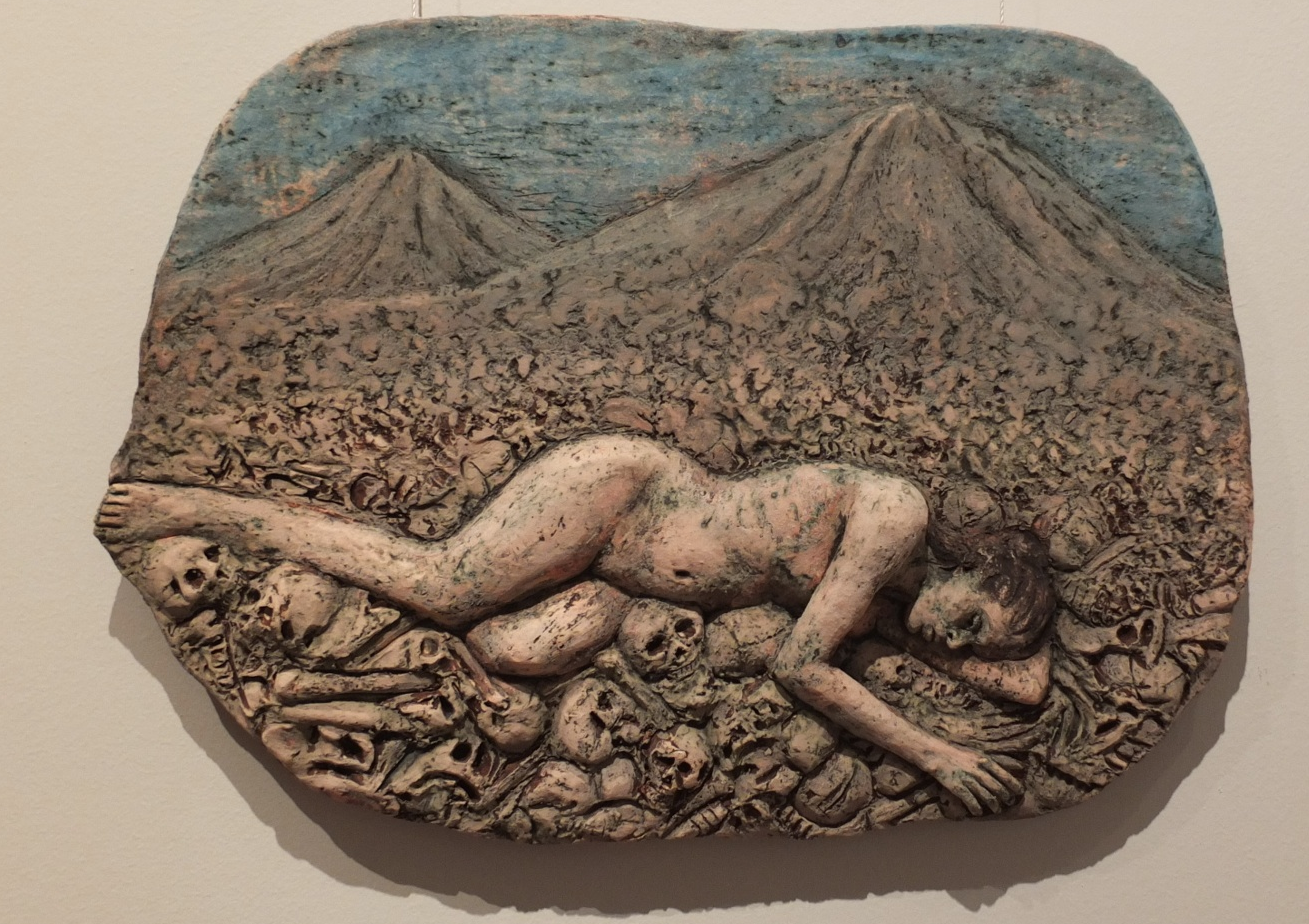

The exhibit features bas-reliefs, from earthenware clay, as well as three towering, Raku-fired totems, which are from Karagheusian’s 2009 installation, A Conversation.

A Conversation, explains Karagheusian, represents 26 intimate souls rising from the ashes of the genocide. The iridescence of the Raku-fired surfaces glimmer with the hope and renewal of new generations. It is clear that Karagheusian works intuitively, by instinct and inspiration, in an attempt to capture the essential qualities of the human spirit, the internal psyche. She has created a private moment with self, past, present and future. The totems, as well as the bas-reliefs, are a poignant tribute to her ethnicity and heritage.

“Some people have expressed the sense of sadness they feel in my work, in both the totems and in the bas-reliefs,” says Karagheusian.

“I was a member of the Armenian Youth Federation as a teen and into my early twenties, where I engaged in social, educational, political, religious and cultural activities that solidified my identity. I could not have felt more proud to be an Armenian.”

For more information about the exhibit, which also features local artists Sharmon Davidson and Jan Nickum, visit Covington Arts here.