By Greg Paeth

NKyTribune Reporter

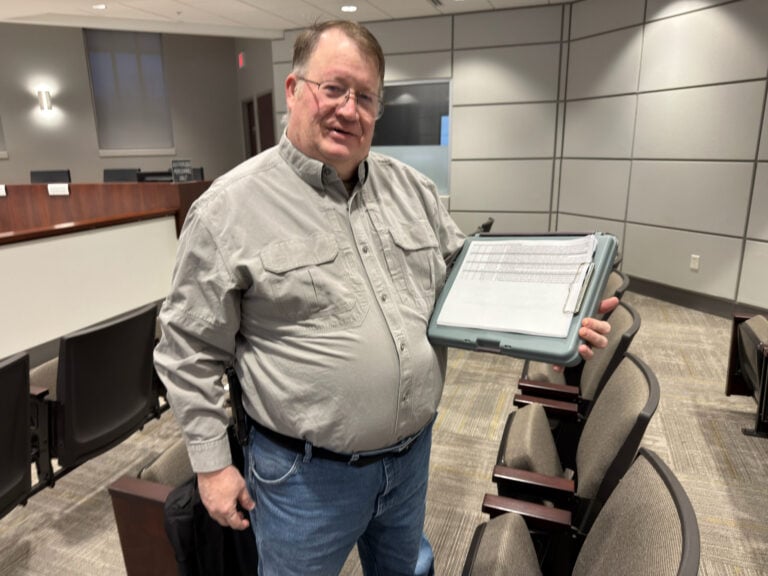

Covington Police Chief Michael “Spike” Jones, now officially retired, insisted that he has no specific plans post-retirement and has not lined up another job that will dovetail perfectly with his 27-year career with the Covington Police.

The only deviation from his generally straightforward responses during a recent interview came when he was asked about running for a Covington office. That’s when he sounded just a bit like a presumptive candidate on “Meet the Press” who has done everything but formally announce his or her plans to run for office X, Y or Z.

“That seems to be the one I’m hearing the most,” Jones said when he was asked about persistent rumors that he intends to run for a city office.

“I love the city. I love the people, and I’m staying (in the city). If there is some way I can serve the city in the future, I’d be happy to do it, but I’ve not made any plans to run for anything in the near future.

“But never say never…(you) don’t know what life will bring. I haven’t made any plans to run for any elected office right now. Sure I’d give thought to it. (But) I’m not out looking for anybody’s job — that’s for sure.”

Based on name recognition and an unblemished reputation, he could be a formidable opponent for any of the four Covington city commissioners or Mayor Sherry Carran a year from now.

There was nothing ambiguous in Jones’ dismissal of speculation that he’s in line to become the next Kenton County Police Chief now that Brian Capps has stepped down to take a job with the U.S. Attorney’s office in Ohio.

The state retirement system for police officers clearly prohibits an officer from retiring and simultaneously lining up another job that would be covered by the same retirement plan, Jones said.

“I haven’t had any conversations with anyone. I haven’t applied for any jobs,” said Jones, who also denied participating in anything as informal as “chatting over a beer” about a job that might open up in the near future. “There are a couple of jobs — one across the river that is intriguing – and I’ve talked to a couple of people about consulting work,” said Jones. The job in Ohio is at Xavier University, Jones said.

The chief stressed that he feels no pressure to make any decisions about his future.

“I feel like I’m young –- I feel good,” said Jones, who will turn 50 in October, when he plans to marry for the third time. His bride-to-be is no stranger to law enforcement.

He said he first met Christie Feldman, district supervisor for the Kentucky Department of Probation and Parole, many years ago when she called for a police backup while checking up on a Covington resident required to follow court-imposed rules.

Unlike his predecessor, Lee Russo, Jones is no newcomer to Covington.

Russo’s tenure lasted five years as the only Covington chief who had not been promoted from within the department. At one point in 2009, 94 percent of police department union, the Fraternal Order of Police, voted “no confidence” in Russo, who came to the job from Baltimore County, MD. That vote was one of the factors that led Russo to step down in May, 2012.

And while the rank and file may have had no confidence in Russo, the former chief had plenty of confidence in Jones. Russo had recommended Jones be appointed assistant chief even though Jones had been playing a leadership role with the FOP at the state level.

When Jones was appointed chief in late June of 2012, he stepped down as president of the Kentucky FOP midway through his second two-year term. He cited the tightrope walk for police chiefs who are, on one hand, part of the city’s management team while also being advocates for the best possible working conditions for the men and women of the department.

“I (had) a fiduciary responsibility to the taxpayers to use their tax dollars in the best possible way to get the highest amount of production in our service,” Jones said. “You never ask a police chief if he could use more people because the answer’s always going to be yes.”

“In our instance, the more people I can put on the street, the safer my policemen are because they have backup more readily available, and the public is safer because when they call the police they might not just have one police officer or two police officers responding to a critical incident. They may have three, which in a pinch, is always better than one. There is safety in numbers.”

As evidence of the fact that the job can be dangerous, Jones pointed out how a suspect fired at police and shot a police dog twice during an incident in April after the suspect had assaulted his mother.

“Those are the things that grab you and make you realize how dangerous some of these moments are when you’re on the street,” he said.

As he looked back at nearly three years as chief, Jones said his one disappointment was that he couldn’t convince the city to hire more police officers. “I wish I had a better impact on being able to increase staffing,” Jones said.

That staffing issue is still percolating as the city prepares its budget for the next fiscal year. Covington now has 106 police officers, an increase of three since Jones became chief, but down 10 from 116 not that long ago.

Jones, who now lives on a 17-acre farm tucked into a rural corner of the southern end of the city, grew up near 17th and Greenup, which is about six blocks from Covington Police headquarters. He is the only child of Jack Jones, who spent 32 years with General Motors at its plant in Norwood, and Cora, a stay-at-home mom who eventually took a job as a “lunch lady” with the Covington schools, Jones said.

Jones quickly rattled off the names of a half dozen other men who grew up in his neighborhood and wound up pursuing law enforcement careers.

“I don’t know if there was something in the water over in those blocks or something we caught,” Jones said.

Jones said many of the guys he grew up with get together when St. Ben’s holds its annual fundraising festival. “It’s a bit of a neighborhood reunion for us. We go back and see who can come closet to winning the beer mug slide by the end of the night. I don’t think anyone’s ever won it.”

He graduated in 1984 from Holmes High School, where he played drums in the Bulldog band and was drum major his senior year.

Jones said the “Spike” nickname originated at Holmes, where one of his buddies got a laugh by calling him “Spike” in front of several other friends, who decided that from that day forward he would be Spike.

After high school, Jones enrolled at Eastern Kentucky University, where he majored in criminal justice with plans to make a career out of his long-held interest in police work.

“I remember as early as the second or third grade kind of daydreaming and thinking about wanting to be the police, watching ‘Adam-12’ reruns and just thinking, ‘That’s got to be the coolest vocation for anyone.’ Of course, we didn’t have Xboxes or Ataris, for that matter, when I grew up or anything electronic, so we played cops and robbers and things like that, and that was how we entertained ourselves.

“I think I developed an interest at that point. I’d see a police car go down the street in front of the house and was just always intrigued with where’s that car going? What are they doing? Is there a call or are they patrolling? So my wheels were always turning,” he said.

Looking back on his 27 years with the Covington Police, Jones acknowledged that he “…made lots of arrests. I have arrested some pretty bad people and I feel pretty good about those arrests. I feel those were the right thing at the right moment.”

But he was hesitant to take too much credit, an attitude that could accurately reflect how he feels about being a police officer. Or, in the alternative, it’s the right picture to paint for someone who might want to campaign for office in the not too distant future.

Later in the interview, Jones said: “You know, and that’s the thing, there’s really not one thing where I can point to myself and say, ‘Yea for me.’ I think the big thing I’m most proud of is having been a part of this team (the police department).”

A moment from years back that he remembers with some precision didn’t involve cuffing some violent perpetrator who was threatening mayhem.

Instead, Jones recalled a “little old lady” in her 80s who lived on Watkins Street when Hellmann Lumber was located nearby on Main Street. Jones said the woman’s backyard shed had been broken into and she was alarmed because she could no longer close the door because the hinges had been ripped out of the door frame.

The chief said he had a cordless drill in his patrol car and Hellmann’s donated some wood screws for his project.

“So I got a handful of screws and went back and fixed this lady’s shed door and I thought nothing of it. And she wrote this really nice letter to me about what a difference that had made and how it changed her perception of police work and what police do and what they do for the community,” Jones recalled.

At a time when police departments all over the country are facing criticism, scrutiny and, in some cases, outright hatred when unarmed suspects – usually African-Americans — are killed or roughed up by police, Jones said police officers and members of the community have to learn how to communicate just like he did with that woman on Watkins Street.

Jones said he thought some of these vitally important issues were explored intelligently during a police-community forum that was held in mid-April in Covington. The panel that was assembled included the Cincinnati police chief, a retired assistant chief from Newport, a representative of the NAACP and Jones.

“The more I hear about what has led up to some of these (explosively violent) incidents, it’s not the incident itself, the circumstances are the tipping point,” Jones said. “What occurred before the incident — maybe a lack of conversation, maybe lack of understanding — is what leads up to that tension and anxiety. I think that’s part of it. A lot of people point to it (and say) ‘It’s the police department. It’s the police department.’

“Well, yeah, we show up when things are not going right. That’s our job. You never call a policeman when (you just say) ‘Hey things are great. We’d love to see you more often. Come on by.’ We don’t get those calls. It’s when things are going wrong . . .The government has a role as well. . .

“If the conversation that occurred at the career center (in Covington) had taken place in Ferguson before that incident occurred, we wouldn’t have even been talking about Ferguson. We wouldn’t even know where it is.

“I also think that in many instances the media’s role sometimes gets compromised between the honest reporting of news and facts – what the First Amendment was intended for — and selling dish detergent,” Jones said.

Jones, who completed graduate work in executive leadership at Northern Kentucky University in 2010, said the department has made numerous efforts to hire minority police officers and has two African-Americans on the force.

But he said the proximity of Cincinnati, where starting salaries are considerably higher, makes it difficult for Covington to compete for a relatively small pool of minority recruits.

Jones also said he and incoming chief Bryan Carter are concerned about the growing Hispanic population in Covington and the unwillingness of some undocumented Hispanics to report incidents to police. The chief urged people who have been victims of crime to come forward without fearing that they will be reported to immigration officials.

He said Covington police eventually got involved in the mugging of an Hispanic man who didn’t want to report the incident because he is in the country illegally. Former Covington Commissioner Shawn Masters led a social media effort to collect money for the man after the March 18 incident near Eighth and Greer streets.

Jones suggested that undocumented criminals have far more to worry about than undocumented crime victims.

As a Covington police career that began in 1988 winds down, it’s clear that Jones could never be described as “trigger happy.” Jones said he fired his weapon once while he was heading home after a shift and saw a pitbull attacking a man in Latonia. “When I got the pitbull’s attention, it decided that I was the next best thing and it came after me. I fired one shot and it retired to its house. I didn’t kill it, but it stopped the attack, and that was what I was after,” Jones recalled.

While he may have had some difficulty recalling great moments of triumph on the police department, Jones had no trouble remembering what he described as his worst day on the force. That was in early January of 1998, when police officer Mike Partin was chasing a suspect on the Clay Wade Bailey Bridge and tried to jump over an opening between the roadway and the sidewalk. Partin apparently slipped and fell into the Ohio River.

Jones wound up helping Partin’s father as rescue and recovery teams searched unsuccessfully beneath the bridge. And when the body was finally recovered months later, Partin’s widow and one of his brothers wanted to view the body, which was discouraged by the coroner because of the ravages of the river.

Jones said he and another officer accompanied the widow and Partin’s brother into the viewing room. “We went in – it was a place I don’t like going back to,” Jones said, his voiced choked with emotion. “That’s one of those times you say, ‘That’s why God put me here’.”

As his career comes to an end in Covington, Jones recalled a story about his first night on duty, Sept. 22, 1988, when he was still living with his parents near 17th and Greenup. Jones said he had his Covington police equipment, including a police radio, in his car and planned to arrive 20 minutes early for his first shift as a member of the department.

What he heard immediately was that an officer had pressed his radio’s “panic button” and was seeking assistance quickly. Jones said he drove north on Greenup and spotted a struggle in the grassy median along 11th Street between Greenup and Scott.

“I looked over and there’s a policeman and a man fighting — rolling around on the ground. The policeman is fighting for his life and I jumped out of my car and helped subdue this individual who had his hand on the officer’s gun and was trying to get it out of the holster and in other hand he had the officer’s badge that he had ripped off his shirt, so I got him handcuffed,” Jones said.

Once the incident was over, Jones talked briefly with the officer, Tony Williams. “I introduced myself and said, ‘I’m obviously new and I don’t want to be late for my first day at work, so do you need anything?’

“He said, ‘No, I’m good, thanks,’ and so I left and I thought, ‘Well, I haven’t even started work yet . ..is this the way it’s going to be every night’?”

Jones then reported for roll call, where he was sitting in the front row with the other rookies when Williams walked in and let every one know that Jones had made a pretty good first impression.

“I don’t know who you are, but you’re all right by me,” Williams said.

I had the great pleasure of working with Spike Jones in the City of Covington. He is a class act and a great example of what a leader should be. I certainly hope that Spike considers another role in the public sector. We could certainly use more people like Spike in our public organizations.