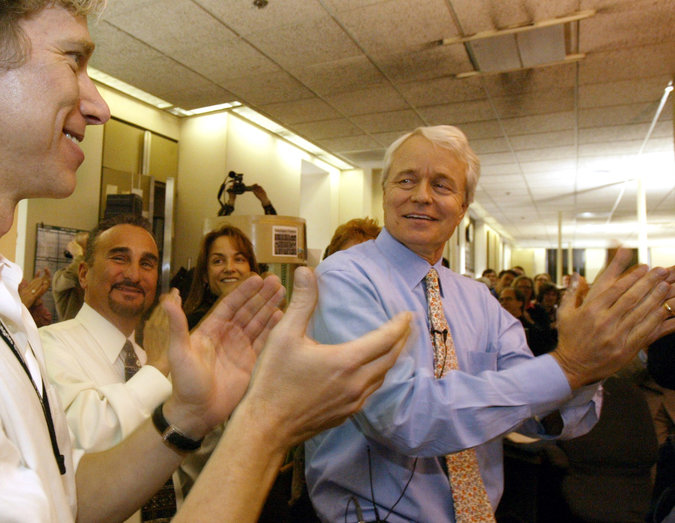

John S. Carroll, a widely admired newspaper editor who restored the reputation and credibility of The Los Angeles Times in the early 2000s even as he fought bitterly with the paper’s cost-conscious corporate parent, died on Sunday at his home in Lexington. He was 73. Lee Carroll, his wife, said the cause was Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, a rare neurological disorder. Carroll also served as editor of the Lexington Herald-Leader and of the Baltimore Sun. He helped deliver 13 Pulitzer Prizes to The Times during his five-year tenure there.

By Al Cross

Director, Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues

The best tributes to the late John Carroll, one of America’s greatest newspaper editors, will probably be written by people who worked with him — those whose journalism and careers he profoundly influenced, and whose work benefited from what Wendell Rawls called his “velvet touch, soft ear, careful tongue and steel spine.”

But many who weren’t on the same payroll as John, including those of us who competed against him and his staffs, can feel after his tragic death that we really did work with him — in that great, collective cause that all journalists should feel: public service that improves communities, states, our nation and our world.

“Kentucky is a better place because of him,” community-journalism specialist Liz Hansen, recently retired from Eastern Kentucky University, said of our friend on Facebook. That’s one of the finest compliments that can be paid to a journalist, and John deserved it — for what he did for the Lexington Herald-Leader, for the newspaper’s service area, for Eastern Kentucky and for the state’s educational system, including the University of Kentucky, where I work.

If there was a sacred cow in the Lexington news media, it was UK basketball, but John directed an investigation of payoffs in the program, and it won the newspaper its first Pulitzer Prize in 1986. That also cost the paper advertising and circulation, and a gunshot through the pressroom windows amid protest rallies and a bomb threat, but the university changed its ways.

John’s reaction to all that summed up the difference in journalism and other trades: “In marketing, the idea is to manage the number of complaints down to zero. That’s fine if you’re making toasters, but a newspaper that gets no complaints is a dead newspaper.”

Earlier, when John arrived to take the editorship of the Lexington Herald in 1979, I was a bureau reporter for The Courier-Journal, which covered all of Kentucky from its Louisville base and enjoyed strong circulation in much of Eastern Kentucky, where the Herald and its afternoon sister, The Lexington Leader, were punching below their weight. But the Knight-Ridder chain, which had brought John in from The Philadelphia Inquirer, put new emphasis on covering the rural region at a time when we started sending it an early edition without late sports — even UK ballgames.

Under John and Publisher Creed Black, a native of Harlan in southeastern Kentucky, the merged Herald-Leader became a real force in Eastern Kentucky, and that was especially important in 1989, when the state Supreme Court ruled the state school system unconstitutional — in a case brought by poor, rural districts. The Herald-Leader’s response was an investigative package called “Cheating Our Children,” which turned over some long-stuck rocks in the region, as John might have said, and had as much or more impact on the education-reform legislation as The Courier-Journal did.

When John left to edit The Baltimore Sun in 1991, I was The Courier-Journal’s political writer, and I can admit now that it was a bit of a relief to see him go. He knew how to recruit good people and manage them in ways that produced a newspaper that was in many ways fully competitive with the larger Courier-Journal. It certainly was with me. In those days, the front line of Kentucky’s journalism wars was on Shelby Street in Frankfort, where our bureau’s address was 614-B and the Herald-Leader’s was 612-A. John’s successors maintained that competitive spirit, and both papers benefited from it; so did Kentuckians, especially those in the far reaches of the state, far from the major cities.

The last decade’s financial pressures on newspapers mean that rural coverage and circulation have greatly declined, at papers in Kentucky and elsewhere. Now my job is helping the smaller, rural news outlets pick up the slack. John Carroll will continue to inspire us.

Al Cross is director, Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues, associate extension professor, School of Journalism and Telecommunications and faculty senator, College of Communication and Information, University of Kentucky.