By Stephen Enzweiler

Special to NKyTribune

On a cold November day in 1920, a letter arrived at St. Mary’s Cathedral rectory addressed to the Very Rev. Joseph Flynn, Vicar General of the Diocese of Covington. It was from William E. Blank, a Cincinnati artist Rev. Flynn had hired to come in and clean the cathedral’s chapel murals painted a decade earlier by local artist Frank Duveneck (1848-1919). In the ten years since their installation, the famous paintings had begun to show signs of wear. Flynn thought that perhaps a cleaning was all that was needed. But Blank explained in his letter that a cleaning wasn’t the answer: the murals were actually in a rapid state of deterioration, and that a radical restoration and preservation action was necessary in order to save them.

Flynn must have been stunned at the news. The murals were only ten years old; how could they have deteriorated so quickly? They were by then already among the most famous church murals in America, and with Duveneck’s death the previous year, even greater attention was being paid to their historical and artistic significance. But there was never any hesitation in the priest’s mind about what to do. In the end, Blank was given permission to do whatever was necessary to save them.

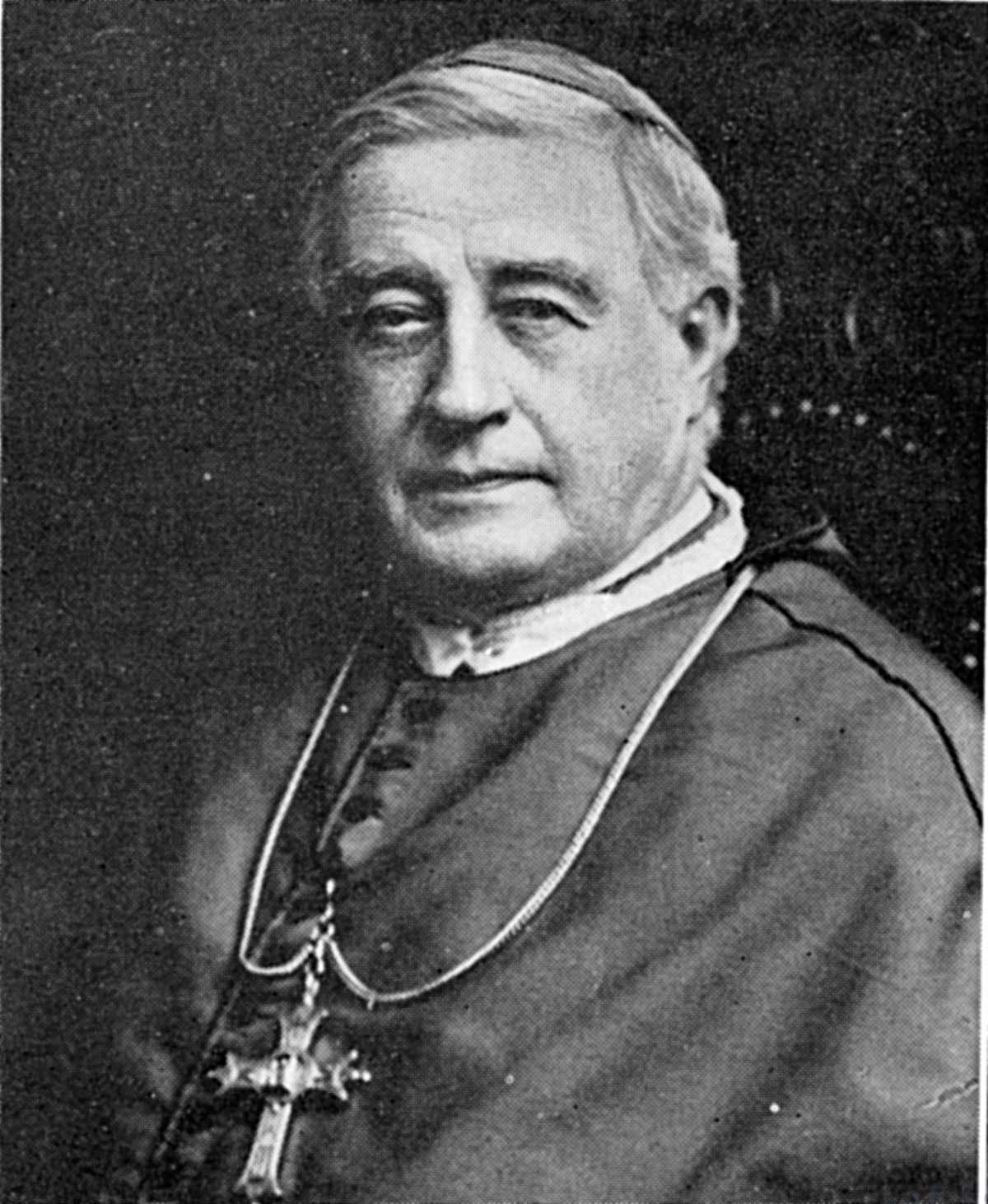

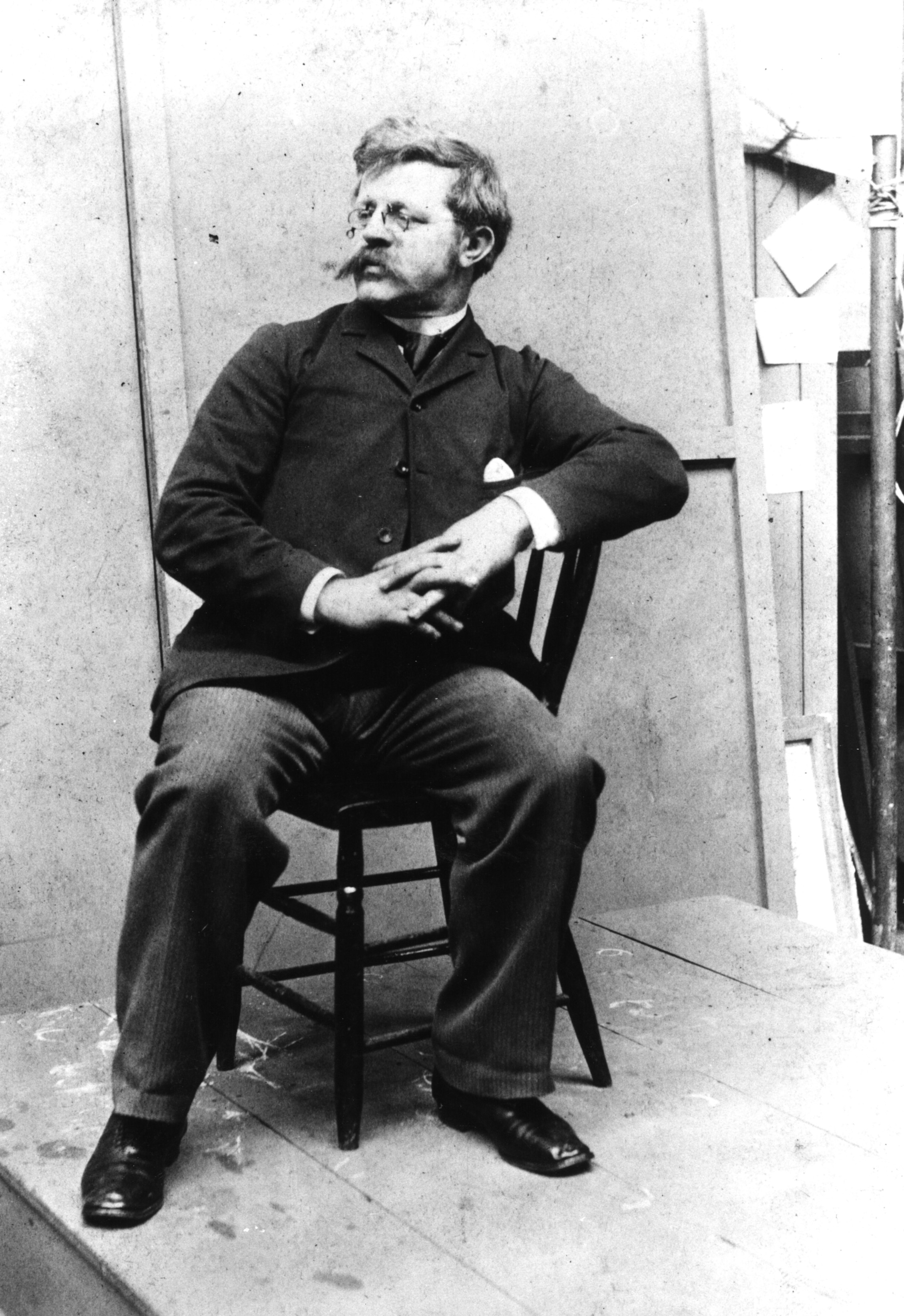

The Duveneck murals can trace their origins to the summer of 1903 and Covington’s third Bishop, the Most Rev. Camillus P. Maes. Frank Duveneck was one of the most famous painters in America at the time. Henry James called him “the unsuspected genius.” Famed painter John Singer Sargent also declared he was “the greatest genius of the American brush.” Bishop Maes, who knew and appreciated fine art, was also a great admirer, and he was determined to acquire the talents of this quiet genius for murals he wanted in the bishop’s chapel of St. Mary’s Cathedral.

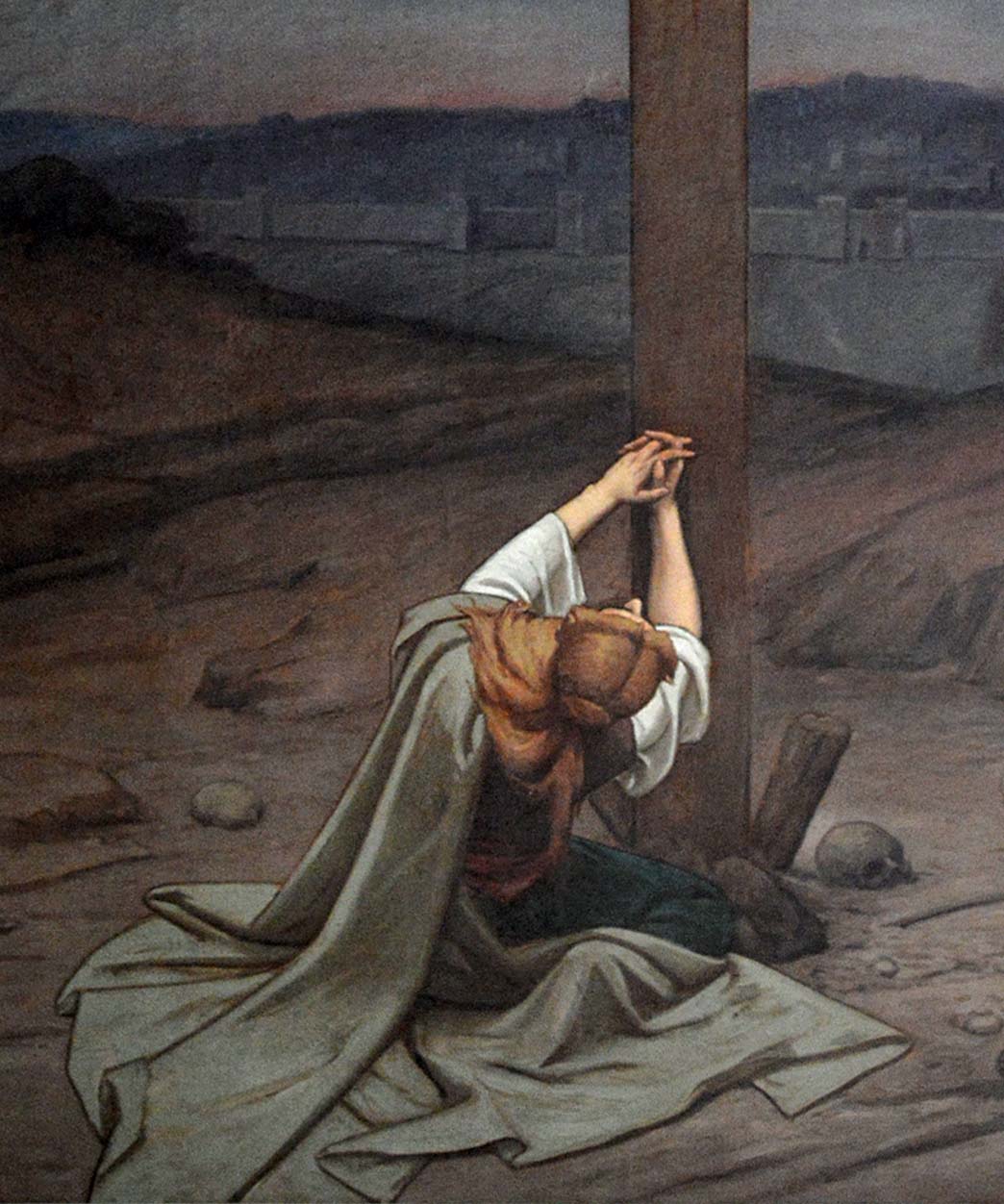

A dialog between the two men began that summer of 1903, and Duveneck eventually sent Maes sketches which the bishop found “striking.” On Sept. 24th, Maes explained in a reply letter his vision for the work: “The central idea is the sacrifice of J.C. [Jesus Christ] on the Cross,” he began. “This is admirably brought out in the Central panel; to carry out the idea that before Christ as well as after the Resurrection, that self-same Sacrifice is the perpetual obligation in the true Church of God, we will – if you please, depict in the smaller panel to the right the Sovereign High Priest of the Old Law (with attendant if you wish) offering the loaves of Bread on the Altar of Propitiation; in the larger panel to the left a priest of the New Law (a Bishop with attendant priests if you like) offering the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, both (outside panels) facing the Crucifixion.”

Duveneck, a devout Catholic who studied as a youth under noted religious painter Johann Schmitt, understood Maes’ ideas perfectly and went right to work. The layout of the main mural itself would take the form of a “triptych” – a single painting comprised of three panels whose subjects center around a common theme. To accommodate the large, 21-foot high canvases required, Duveneck painted them in his roomy studio at the Cincinnati Art Museum, a space given to him because of his teaching position with the Art Academy.

For four and a half years he painted. In December 1909, he put the finishing touches on the last panel, then put down his brush. The triptych was finished, along with a second, smaller mural destined for the chapel’s upper west wall, depicting Christ breaking bread with his disciples at Emmaus. The following month, amid great fanfare and public excitement, the finished three-panel triptych and smaller mural were exhibited in the main entrance hall of the Cincinnati Art Museum. They would be installed in the cathedral’s chapel later that May.

But by the time William Blank was hired to clean them in 1920, the famous works were in bad shape. “After careful inspection,” he wrote Flynn, “I found the paintings were in worse condition than at first expected.” In the first place, he pointed out, the paintings had been cut up in sections in order to obtain a smooth surface when glued to the wall, but that “an improper and impractical method was used in hanging them.” This resulted in a rough, defective surface that gave it a wrinkled appearance. Additionally, he noted the glaze used to protect the painting’s surface had turned cloudy and “blurred the pictures,” so much so that the figures in the paintings looked “almost beyond recognition.” He blamed the problem on a primitive glaze made from what was called the “buttermilk process.” This was a popular French technique, made by mixing milk, slaked lime and linseed oil together and was thought to be a satisfactory substitute for more expensive glazes. But in wet and humid weather, the mixture tends to grow moist, soften and ferment. It also badly damaged Duveneck’s original underlying paint.

Blank had his work cut out for him. He first removed the canvases completely from the chapel walls and stripped off the defective glaze. He then set about carefully retouching the damaged areas of surface paint laid down by Duveneck’s own hand. He cleaned the canvas backs as well, applied new sizing, then carefully rehung each section of canvas with a new, more permanent glue of his own creation. He preserved his work by applying “a hard and transparent glaze” of his own mixing that “not only acts as an everlasting preservative, but also restores the colors to their natural lustre.”

Blank’s restoration efforts have lasted to the present day. The Duveneck murals we see today at the Cathedral Basilica of the Assumption are as bright and colorful as the day he finished them. They remain one of America’s great national treasures of sacred art. But that distinction almost didn’t happen. It was thanks to the ingenuity and skill of a little known artist named William E. Blank that Duveneck’s murals have been preserved for future generations to enjoy.

Stephen Enzweiler is a writer and journalist. He has been a columnist for the Kentucky Enquirer, the Oxford Citizen, and was a senior editor at Y’all Magazine. He is the author of Oxford in the Civil War: Battle for a Vanquished Land (2010).