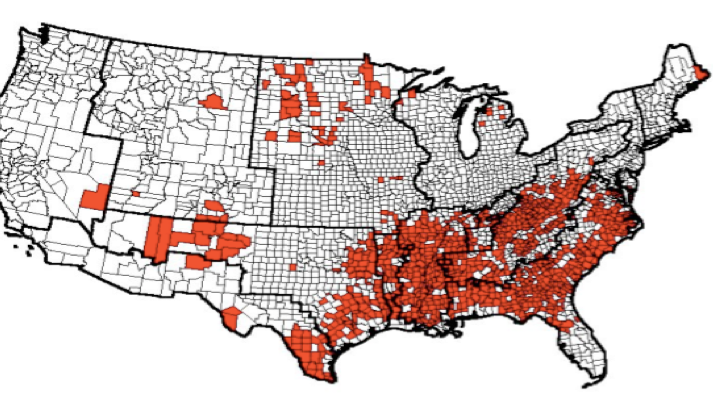

We need to understand the reasons why eastern Kentucky has not made the same level of progress as other Appalachian coal states before we can develop and implement strategies to grow a vibrant diversified economy.

Additionally, we need to study the best practices in southern Ohio, West Virginia, southwest Virginia, and northeastern Tennessee for productive planning. And, we must not be fearful to admit our failures while celebrating our successes in advancing eastern Kentucky.

This column is intended to use of the ideas from colleagues and experts in various aspects of Appalachian Kentucky to begin the conversation and encourage greater research. A gathering will be held to share ideas on the topic.

Persons interviewed for this column and some of those quoted suggest six overarching factors and reasons for Appalachian Kentucky not advancing at the same rate as other states. Those factors are:

The dependence on coal, a resource extraction industry, with boom and bust cycles, in which much wealth left the area, and until the dramatic recent loss of coal jobs did not produce the urgency and coordinated efforts to diversify the economy. Even when the coal markets were strong, the coal producing and impact counties had some of the highest poverty and unemployment rates and worse health statistics in the nation.

The failure to have an interstate highway crossing the coal fields either diagonally or horizontal to open up markets and greater commerce.

The absence of a public research university based in the coal fields has reduced civic capacity, educational levels, and funding for research which stays in the mountains.

Established political and institutional boundaries which divide the region instead of enhancing regional collaboration: the large number of small counties creating a competitive and parochial spirit; the region divided into several area development districts preventing a coordinated regional leadership approach; the two excellent regional universities based outside the coalfields divide the coalfield service area.

The region has not had sustained and focused efforts to carry out the solutions to stymied economic and social development, but, instead reacted to changing economic circumstances.

Leadership, the so-called elephant in the room, has been a major factor and one which many experts are hesitant to go on the record to discuss since comments can be so misunderstood. The lack of successful, widespread effective leadership inside and outside the region focusing on improving the mountains is a complicated issue. Leadership does not just include elected office holders at various levels and types of regional and community participation. Emerging leadership and the development of more inclusive, servant leadership models is promising. Some of the factors limiting successful leadership in the past include: the large number of small counties creating a competitive spirit; the absence of university leadership; high poverty and jobless rates creating an unhealthy political environment where office seekers seek to help their own family and friends.

The future of Appalachia

Ron Eller, the author of “On the Future of Appalachia” in 2012, in response to my question writes, “Development across Appalachia has been uneven due largely to differences in leadership — the absence of creative political leadership in some areas and, in other areas that have been more successful, the willingness of leaders to take bold new steps and plan for long term development rather than short term responses.

“Essentially the difference within the region lies in the character of the local political culture and its ability to respond to change and local conditions. As is true of almost every other aspect of the region’s culture and history, the experience of eastern Kentucky is the most intense and extreme example of the failure of political and institutional leadership to address the persistent “structural” problems and inequalities that have plagued the region for decades.”

Eller adds that he believes the lessons of that history call for bold policy reforms in five interrelated areas, only one of which involves the job training and market-oriented initiatives that have been the mainstay of east Kentucky political leaders. They are:

“Land Reform – Land ownership, usually held by non-local and resource extraction entities, has long been a problem throughout Appalachia;

“Economic Reform – Historically the Appalachian economy over the last century has been tied to the vagaries of national and international market demands;

“Political Reform – Building a more diversified economy and healthier communities requires not only land reform and a different way of thinking about economic development, but a revitalization of the democratic spirit in Appalachia;

“Institutional Reform – Institutions are the structures through which the moral capital of a society is visible. Attitudes toward the land and environment, economic equity, and political expectations are reflected in the character and quality of our institutions; and,

“Cultural Reform – Like most areas of the nation, and increasingly the world, Appalachia has undergone dramatic cultural change since World War II. A society that once took pride in group identity, cooperation, politeness, mutual respect, and humility now struggles with hopelessness, competition, addiction and self-indulgence.”

West Virginia has been able to move about one-half of its counties out of the distressed category partially due to some advantages eastern Kentucky does not has. The type of coal they had withstood some of the market changes, more petroleum, and they have universities based throughout the coal states, and have a stronger tourism industry.

Why West Virginia?

Peter Hille, the director of the Mountains Association for Community Economic Development (MACED) observes that part of the charge to the Kentucky Appalachian Task Force in 1994 was to explore why West Virginia had garnered more ARC investment to Kentucky. Hille insight includes his personal ABC’s.

A— A is for Appalachia, and all of WV is in the ARC region, so it can’t be ignored as it often is in KY.

B— B is for the Benedum Foundation. We have no similar philanthropic entity investing in eastern KY.

C— C is for Robert C. Byrd, who did a lot of good for his home state.

D— D is for Development, and I got to see how there was much more synergizing of development efforts in West Virginia than in Kentucky over much of the last 25 years. SOAR is a notable shift in that regard.

E— E is for East Coast which West Virginia is much closer to and derives a lot of benefit from.

F— F is for Fun. West Virginia has significantly outspent Kentucky on promoting tourism, and being closer to the East Coast helps with that as well.

Southwest Virginia

Southwest Virginia has had great success in jettisoning distressed counties through regional economic development with state leaders, university staff and faculty, and with community leaders. They have developed a strong cultural heritage tourism program which has generated income and encouraged professionals to move into the region.

Hindman attorney and banker Bill Weinberg adds that Virginia had longstanding funded regional economic development legislation that rewarded entities and governments for working together regionally. Weinberg makes a point echoed by others related to leadership and that the region has not wisely used the severance taxes that have been returned to the counties.

Weinberg was a part of a group who began the East Kentucky Leadership Foundation in 1987 to host annual conferences to encourage eastern Kentuckians to work together.

As the result of a conference session in April, 2012 “Distressed Counties in Eastern Kentucky: Why Are We Behind?” James Hurley, the former president of the University of Pikeville and Jason Belcher the first director of Central Appalachian Institute for Research and Development (CAIRD), penned a research paper. Their research demonstrated “Institutions have played a large role in shaping the manner in which groups cooperated or failed to cooperate; in the case of southwestern Virginia, institutions have achieved a higher degree of cooperation than those in eastern Kentucky.

To understand why, we must first look back to 1996 when the Virginia Assembly passed the Regional Competitiveness Act, which included the following key provisions:

“It shall be the policy of the General Assembly to encourage Virginia’s counties, cities and towns to exercise the options provided by law to work together for their mutual benefit and the benefit of the Commonwealth.

“The General Assembly may establish a fund to be used to encourage regional strategic planning and cooperation. Specifically, the incentive fund shall be used to encourage and reward regional strategic economic development planning and joint activities.”

According to Hurley and Belcher, “The state legislature did create such a fund, which awarded grants and funding to regions that developed projects to improve economic competitiveness and development. The Regional Competitiveness Act gave Virginia’s institutions such as local governments, non-profits, and universities an incentive to coordinate their efforts. According to Neal Barber, Director of the Urban Partnership, the results since the passage of the Regional Competitiveness Act have been striking: most of Virginia’s regions have seen a significant increase in co-operative agreements among localities for the provision of individual activities, services, or functions. In the Richmond area alone there have been over 100 such agreements.

“The Southwest Virginia Coalfield is one of the regions that has benefitted from the Regional Competitiveness Act, but it is also part of a larger state system. The characteristics of the state system in Virginia are very different from Kentucky, and these factors contribute directly to the different economic performance. The southwest Virginia coalfield region has been a beneficiary of regionally focused cooperative agreements. Indeed, the growth of VCEDA, the Virginia Coalfield Economic Development Authority directly resulted from the 1996 Regional Competitiveness Act.

Hurley and Belcher add “Significantly funding for projects comes in part from coal severance money, which Virginia law requires to be returned in proportion to the county in which it was mined. Kentucky’s coal severance fund does not include a similar provision to return severance money in proportion to the county from which it was mined. Most importantly, the Virginia coalfield partners and contributors created a shared vision for their region.

“The vision created completely rebranded the region; instead of the Southwest Virginia Coalfields, it is now known as Virginia’s “E-Region.” The E stands for energy, education, and e-commerce. Applying resources in support of that common vision has yielded concrete results,” Hurley and Belcher explain.

Kentucky’s data guru Ron Crouch points out that information released in April 2016 shows a number of areas where Kentucky Appalachian counties fare poorly with all other Appalachian counties: (1) smaller population in Kentucky counties where other Appalachian states have some counties with more urban populations sizes, (2) population with a high school degree, (3) labor force participation rates (informal economy issues), (4) all income indicators, (5) poverty indicators, (6) disability rates, (7) surprisingly low rates of veteran status.

As the region plans its future, it is important to understand what Crouch explains about how the region’s population and economy has changed. Crouch says Appalachian Kentucky “is now a healthcare economy and coal mining has been in decline for decades, not a recent War on Coal, 75,000 coal mining jobs in 1950 vs. 25,000 in 1970, and 12,000 in 2000, leading to a female- dominated employment economy compare to the rest of Kentucky.”

Campbellsville University professor Dr. John R. Burch observes in his book Owsley County, Kentucky, and the Perpetuation of Poverty, that the problems of Eastern Kentucky relate to the problem of way too many tiny counties with entrenched political families who are more interested in meeting their needs than that of their constituents. This dates back to at least from the early 1800s during the period when counties were being created by the legislature with little consideration as to why. During the War on Poverty, when federal funds flowed into the region to address poverty, little of that money was ever seen by the truly poor as much of it was diverted to whatever needs those that controlled local governments and the regional community action programs desired. This same dynamic can be seen with the coal severance monies in recent decades, which was spent by county officials with little permanent to show for it. Despite the claims of county officials today, the priority continues to be to privilege their needs of their county over the needs of the region. It is the continued focus on the county that differentiates Eastern Kentucky from its Appalachian counterparts in other states.

Dr. Burch adds, “While the coal counties in other parts of Appalachia have had the same fundamental challenges, their states did not allow for the creation of Little Kingdoms, as Robert Ireland described the process of county construction. Unfortunately, the latest constitution made it virtually impossible to merge counties in the commonwealth, since it was written by the very politicians that benefitted from the system in the first place.”

Eller observes that “Coal mining employment has been declining since the end of WWII and (except for a brief rise in employment in the 1970s) has been a major factor in the economic stagnation of the coal fields despite rising coal production. Writers have been calling for new directions in the eastern Kentucky economy at least since the late 1950s but as I documented in Uneven Ground, those efforts were either largely ignored or failed to address the underlying weaknesses in the region. So the failure of leadership in the region dates back many decades, during which other areas of Appalachia were seriously laying the foundation for longer range change.”

Too many stereotypes

Other state leaders and Kentuckians must share some of the blame for the lack of support and coordinated efforts. The unfortunate and outdated stereotypes of the region lingered in the minds of Kentuckians who question if more resources should be invested in the mountains. The infamous “Winchester Wall” boundary to getting funding in the East was knocked down by some mountain legislators who revolted in the late 1980’s. Pike County Judge-Executive Paul Patton was elected as lieutenant governor and then as the state’s first two term governor leading to greater attention and funding in the mountains.

The eastern Kentucky coalfields has had the benefit of two powerful congressman who brought funding and support for local and regional projects: Congressman Carl D. Perkins who served from 1949 to 1984 and Congressman Hal Rogers who assumed the mantle of the new Fifth Congressional District after redistricting in 1995. Congressman Rogers aided the development of civic capacity and leadership founding regional organizations which had county level participation.

The first was Forward in the Fifth to address the challenge of the Fifth having the poorest educational rates in the nation. Among other powerful organization were PRIDE (trash clean up and beautification) and UNITE (against drugs).

The region made progress thinking and planning regionally for several years with the development of the Kentucky Appalachian Regional Commission under the leadership of Ewell Balltrip.

Balltrip adds, “Sustained efforts are organized programs and activities that continue over long periods of time. Too often our region has seen worthy programs initiated only to have them discontinued before they have had adequate time to bring about the change or generate the outcomes they were intended to produce. In the case of state and federal initiatives, these efforts are often truncated by political decisions.

“As an example, the Kentucky Appalachian Commission was created by Gov. Paul Patton in 1996. Eight years later, Gov. Ernie Fletcher effectively closed the Commission and discontinued its work by removing funding for it from his first budget. (Disclaimer: I was the executive director of the Commission from 1996 to 2004. My use of this as an example is not a case of sour grapes, but rather is an illustration of how changes in political outlook, philosophies and objectives can impact regional development activities.) Whether the Commission was effective or not is a debate for another day. However, the time it had to fully accomplish its mission was not sufficient.”

The nature of the political system, especially at the state level, often cuts short the time worthwhile efforts are given to achieve their objectives, explains Balltrip.

“The Central Appalachian Institute for Research and Development (CAIRD) was a worthy effort that failed early in its infancy,” Balltrip says. “This was due not to political considerations, but to a lack of funding (which one could argue was at least a policy decision if not a political decision). CAIRD, whose origins were with the Kentucky Appalachian Commission, was conceived as a means to address the need for access to research and development support for regional issues. As the region does not host a research university, CAIRD was designed to apply academic firepower and knowledge to difficult topics. CAIRD was unable to sustain its efforts.”

The region has seen many well-intended, well-designed initiatives move off their original mission, hampering efforts to address some of the most challenging problems, Balltrip points out. Shifting and unfocused efforts send mixed messages to political and civic leaders at the local level, leading to confusion about the purpose and intent of the efforts. The state program that returns a portion of the Commonwealth’s coal severance tax to coal-producing counties provides an example of this. Over the life of the program, which began in the 1970s, the focus of how the funds directed to the coal counties could be spent has shifted.

While the overarching concept driving the program has been to provide resources to finance activities that support diversification of the counties’ economies away from coal, the legislated details of how the money can be spent has changed from time to time. With these changes come alterations in public policy focus and the application of that policy, Balltrip maintains.

We need to rethink higher education for the region, says Tom Matijasic, history professor at Big Sandy Community and Technical College.

“All models are designed to fit urban and suburban areas. They just don’t fit our region. If the University of Pikeville is to join the state system, it must be a university that can offer something to all Kentuckians, not just eastern Kentuckians. If properly integrated with UPike and Morehead State University and Eastern Kentucky University, the community college campuses throughout eastern Kentucky can serve as a stepping stone which will allow the children of the working class to access higher education. UPike is already transitioning into what could become Kentucky’s Polytechnic University serving the state much the way that Virginia Tech serves the people of Virginia; Cal Tech the people of the Golden State; Georgia Tech the people of Georgia.

“Dividing the territory of eastern Kentucky between two state supported universities does not make sense, Matjasic explains. “Dividing the majors and programs does make sense. Making those majors and programs more accessible to everyone, especially the children of the working class, makes the most sense of all.”

SOAR offers hope

The dramatic loss of coal jobs encouraged Governor Steve Beshear and Congressman Hal Rogers to form Shaping Our Appalachian Region (SOAR) in fall, 2013. The Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) which has provided a mainstay of funding and direction for eastern Kentucky and Appalachia has been very supportive of SOAR with both resources and staff. SOAR has the potential to encourage cooperation and collaboration and build a comprehensive vison and team to rebuild the economy while forging a New Economy which can enable the region to compete in the changing world. Governor Matt Bevin has been very supportive of SOAR.

Regionalism, collaboration, and sharing best practices have been promoted by the Kentucky Highlands Promise Zone under the leadership of Sandi Curd. President Obama named the eight county area in southeastern Kentucky the first rural Promise Zone.

Embracing collaboration and forfeiting a culture of competition will not occur overnight. Collaboration and altruism is simply not in some people, leaders’ and institutions’ DNA. As more money is sent into the region in this period of crisis and opportunity, we must be very transparent about those funds and their results. Will the funds grow certain organizations and institutions’ payrolls, or will they make the impact that the funds are intended? Who is benefiting?

In a region which is in economic shock and for many people who have lost hope, SOAR offers hope. There is a potential for a new generation of leadership that is not condemned to repeat the mistakes of the past.

Millennial Mae Humiston, the development associate from Community Farm Alliance voices this new optimism.

“SOAR has, in a way, legitimized conversation about what WE as a people on the ground every day can do about our region’s economic status…. However, it seems that in many of the places moving out of “distressed” and into “transitional” designations, leadership has lifted up and truly invested in the many ideas and efforts around economic diversification in a more intentional way than has been demonstrated here. Many people hope for a new era of the coal industry, but often these conversations and declarations take the place of conversations that could inspire or promote ideas that can sustain and lift up our region, regardless of the status of coal. Talking about diversified economies that capitalize on our natural beauty, the artistic and culinary skills of our people, and the immense potential of our youth in any way threaten or take the place of coal, but that has been the way it has been framed – intentionally or not – when local and state leadership use their time to talk about the way things used to be and not the way things could be.

Humiston adds, “I absolutely believe in the potential of this region and we cannot afford to ignore our people’s intelligence, passion, and creativity for the sake of politics. I think you will find many others agree. “

There are many positive developments and more coordinated regional efforts underway.

Former Governor Paul Patton poses a challenge and a solution. “I think being so far from an interstate is a major problem which we cannot not overcome but for which we can compensate. A group of us working with One East Kentucky have developed a unique proposal to give us a compensating asset to attempt to rebuild our economy before all our skilled workers have left the area.”

Despite drastic cuts in K-12 funding mainly caused by loss of enrollments, eastern Kentucky schools lead the state in graduation rates and college and career readiness. Remarkable improvements have been made and teachers and their students are being prepared for the New Economy workforce.

As an example, the Kentucky Valley Educational Cooperative (KVEC), which serves 19 school districts in 14 counties, had the largest roll out of Next Generation classroom technology in rural America. Their remarkable work can be viewed on the digital platform www.theholler.org. They recently held a sharing of teachers’ innovative classroom projects in which over 10,000 people from around the world watched live telecasts via The Holler. The future leaders who will transform the region are in these classrooms.

Challenges in eastern Kentucky have presented opportunities. A window is open to advance the region. Part of opportunity is understanding what other coal regions have done successfully and to learn from our missed opportunities.

Ron Daley is the Strategic Partner Lead for the KY Valley Educational Cooperative. He is an employee of Hazard Community and Technical College and lives in Hazard, KY.