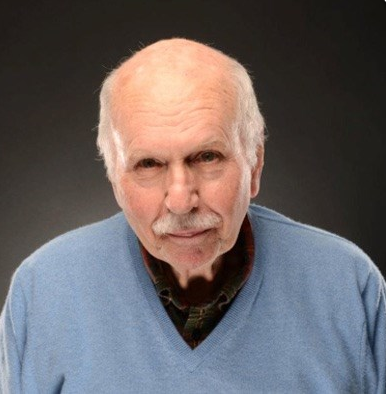

Editor’s Note: Former long-time Courier-Journal sports editor Earl Cox died Tuesday at the age of 86.

Earl Cox was a Kentucky original, a guy who grew up in Irvine – or “West Irvine,” as he liked to correct me with a laugh – and reached his lifetime dream when he became executive sports editor of both The Courier-Journal and The Louisville Times in the mid-1960s.

We had much in common. I was born in Mt. Sterling, about 30 miles from Irvine on the fringes of the Eastern Kentucky Mountains. We both worked at The Lexington Herald before moving on to The C-J. And we shared the kind of affinity for the commonwealth and its sports teams that only native sons and daughters can truly appreciate.

From 1977, when internal politics caused Earl to lose his job as executive sports editor, he became a columnist at more or less than same time I was succeeding our friend Dave Kindred as C-J sports editor and lead columnist.

We had different styles and different responsibilities. Earl took advantage of his vast statewide network of contacts to write a spicy notes-type column. I covered the major sporting events and my columns usually led the sports section. Between us, I think we gave C-J readers a comprehensive and diverse view of what was happening in sports at the national, state and local levels.

I’d be lying if I said we always saw eye-to-eye. In the weeks and days leading to U of L hiring Howard Schnellenberger to revive its football team in 1984, for example, I kept writing that it was going to happen. Earl was just as convinced it wasn’t.

One day he came into my office and said, “Billy, you’ve got to stop writing that s—t about Schnellenberger…You’re embarrassing yourself.” I smiled, shrugged and knocked out another column that the deal was going to happen.

Like almost every kid growing up in rural Kentucky in the 1940s, Earl was a diehard fan of the Kentucky Wildcats, particularly Coach Adolph Rupp’s basketball teams. When U of L began pushing for a basketball series with the Wildcats in the late 1970s, Earl swore it would never happen.

But after it did, to his credit, Earl tried his best to give the Cards fair and equal treatment in his columns. Trust me, though, he loved the Big Blue about as much as he loved the Boys State High School Basketball Tournament.

Soon after Earl joined the C-J staff in the late 1950s, he became the high school sports editor. At the time, considering that the paper had home delivery in all 120 Kentucky counties, the high school job carried with it a lot of power and influence.

From one end of the state to the other, Earl’s prep columns were a must-read not only for coaches and players, but also for superintendents, principals, and legislators in Frankfort. The beat was so big that Earl was given an assistant. One of them, Bill Endicott, left the C-J for the Los Angeles Times, and another, Bob White, succeeded Earl when he moved into administration in the mid-1960s.

Earl was at his best working “the slot,” which is a newspaper term for the guy who lays out the pages and decides what headlines go on what stories. In our day, The C-J had four editions, meaning that essentially we put out four different papers every night. As deadlines approached and stories had not yet been called in (we didn’t have computers back then), Earl stayed cool. If the pressure ever fazed him, he didn’t show it.

Earl’s godfather at the C-J was Norman Isaacs, whom Barry Bingham Sr. brought in to run both papers as executive editor. On the surface, Norman and Earl were unlikely allies – one a WASP country boy from Irvine, the other a sophisticated Jewish intellectual from New York City.

But Isaacs liked Cox’s blunt ways and self-confidence, probably because they mirrored his own. So with longtime C-J sports editor Earl Ruby – one of Cox’s heroes – nearing retirement, Isaacs decided to relieve Ruby and Louisville Times sports editor Dean Eagle of their administrative duties, and turn both paper’s sports departments over to Cox.

The new arrangement wasn’t made official until Ruby retired in 1967. The lead columnist for each sports section was allowed to keep their “sports editor” titles because it made it infinitely easier to get credentials and get the attention of publicity folks. But the departments both were run by Cox, who was given the new title of executive sports editor.

After Ruby’s retirement, Eagle moved to The C-J from the Times and the young, but immensely talented, Kindred was named sports editor of The Times. Then, after Eagle’s untimely death from a heart attack in 1972, Kindred moved to The C-J and Dick Fenlon became the Times sports editor.

That’s the way it stayed until 1977, when Dave left for The Washington Post. Although I had a great job at the time, having succeeded the beloved Joe Creason as The C-J’s general columnist in 1974, I decided I wanted to get back into sports and was named to succeed Kindred, with Fenlon staying at The Times.

Cox had first approached me about coming to Louisville in the early 1960s, when I was working full-time at The Lexington Leader (afternoon paper) and going to school at Transylvania University. I turned him down the first time because I wanted to finish my education in Lexington. But he told me I’d have a job waiting in Louisville as soon as I graduated.

He was as good as his word.

When I had to take off four months for Army basic training in 1967, Earl had the C-J mailed to me at Ford Ord, Calif., so I could keep up with the news at home. At the end of a long day of marching and packing a weapon and running obstacle courses, I can’t begin to tell you what a morale-builder it was to find a C-J waiting for me on my bunk.

In 1968, I left the C-J to work for Sports Illustrated in New York City. As relayed to me by Kindred, Earl’s comment was, “Don’t worry – he’ll be back.” He was right, but only after I had spent four of the best years of my life working with the incredibly talented writers and editors on what had become the nation’s best-written magazine.

However, I didn’t come back to Earl’s sports department. I wanted to see if I could do other things in journalism, so I spent five years as a special projects writer, investigative reporter, features writer, and general columnist.

But my heart belonged to sports, so I jumped back into it when I got the opportunity. For almost a decade, from 1977 through the end of 1986, Earl and I did our respective things for the C-J sports section. I always looked forward to seeing Earl in the office because he usually had a good rumor or two that he was more than happy to share.

At the end of 1986, less than six months after the Binghams had sold the papers to Gannett, Earl and I left at more or less the same time. It wasn’t any kind of concerted effort on our part; it was just that we both had independently reached the same conclusion at the same time — that our careers would suffer under the new regime.

That was the hardest professional decision I ever had to make, and I know Earl felt the same. We both loved The C-J and the world-class journalism it practiced. But we also knew it was never going to be the same under Gannett, so we took our heavy hearts and moved on.

Thanks to his friend John Harrelson, Earl went to The Voice-Tribune of St. Matthews and took many of his readers with him. With editing less stringent than what he had known at The C-J, Earl was more free to vent about whatever was on his mind. He made some people mad, as columnists worth their keep always do, but he also increased the paper’s credibility and circulation dramatically.

I’ll always remember Earl at the Boys State High School Basketball Tournament, his favorite event. He would take a seat on the front row, at midcourt, king of all he surveyed. As I watched his friends and sources virtually line up to pay their respects, I always thought this is how it must be when the Pope holds an office in the Vatican.

As a boss, Earl was never subtle. He let his writers and editors know what he liked and didn’t like, sometimes bruising feelings in the process. In cutting stories, he sometimes would use a machete instead of a stiletto. But he loved guys who could write well on deadline and get it right.

He had a good news sense and he had a nose for talent. It was Earl who brought Dave Kindred out of Bloomington, Ill., and gave him the opportunity to show off his special way with words. One of the first assignments he gave Kindred was to travel the state and write about high school basketball. The idea was to teach him about Kentucky, and, more importantly, let him spread his wings as a writer.

Earl loved Dave’s work so much that he once told the staff, “I want all you guys to write like Kindred.” Unfortunately, all that did was spawn a bunch of Kindred imitators who didn’t have Dave’s talent. Sometimes the imitations were downright painful to read.

One thing I always respected about Earl was that he cared just as much about academics as athletics. He loved to brag about the scholastic achievements of Scott, Sarah, and Ellen, his three children, and he would always ask others about how their kids were doing in school. He also had nothing but praise for his wife Carolyn, whom he always credited for the kids’ successes.

The funniest story I can remember about Earl came after we had left The C-J. We both signed on with Lexington television stations to do some commentary, me with WKYT and Earl with WLEX.

Some genius at WLEX decided that Earl’s bald head was too shiny under the studio lights, so he forced him to wear a wig. It was maybe the worst wig I’ve ever seen. It sat on Earl’s head looking for all the world like a Davy Crockett raccoon hat from the 1950s. Sometimes it seemed ready to slip.

All the while, Earl kept doing his commentary, serious as he could be, and that only made it funnier. Suffice it to say the wig lasted about as long as it took Rex Chapman, one of Earl’s favorite UK players, to throw down a dunk.

The past couple of years, Bob White and I tried to meet Earl for lunch. We never worked it out, much to my regret, and it was usually because Earl just didn’t feel up to it. So I missed the chance to thank him, one more time, for the things he had done for me, and to laugh with him about people and places we both knew and loved.

Earl always said that there were four things that tied all the people of Kentucky together – the State Fair, UK basketball, the State Tournament, and The Courier-Journal. That’s not true today, but it was when he said it. He became a mover and shaker in all those areas except the State Fair, although, for all I know, he may have been out there, too, trying to convince a judge that the best apple pie in the commonwealth came from Irvine.

Billy Reed is a member of the U.S. Basketball Writers Hall of Fame, the Kentucky Journalism Hall of Fame, the Kentucky Athletic Hall of Fame and the Transylvania University Hall of Fame. He has been named Kentucky Sports Writer of the Year eight times and has won the Eclipse Award twice. Reed has written about a multitude of sports events for over four decades, but he is perhaps one of media’s most knowledgeable writers on the Kentucky Derby