By Berry Craig

NKyTribune columnist

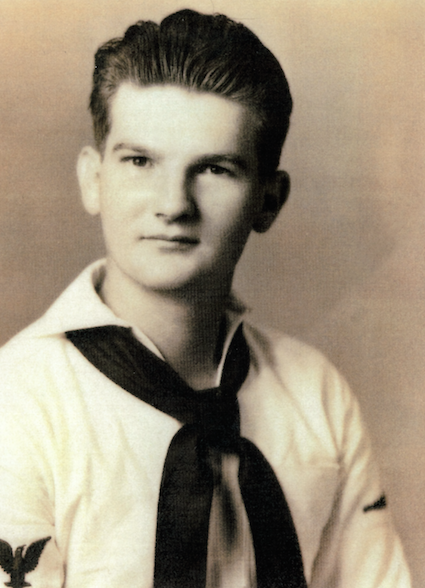

Dec. 7, 1941, seemed like an ordinary Sunday morning in port for Gunner’s Mate Third Class James Allard Vessels of Paducah.

His ship, the USS Arizona, was one of seven battleships moored in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The navy called the lineup of powerful dreadnoughts “Battleship Row.”

Vessels, who died in 1981, rolled out of his bunk about five-thirty in the morning. He pulled on his white uniform, ate breakfast, and headed topside for a friendly game of acey-deucy on the antiaircraft deck. He planned to attend Sunday mass later.

The western Kentuckian didn’t finish the card game or make it to the worship service. At 7:55 a.m., Japanese warplanes attacked, bombing America into World War II.

The 608-foot Arizona, BB39, was a prime target. “When general quarters sounded, I ran for my battle station up in the mainmast,” said Vessels, then 22-years old.

He and eight shipmates climbed to an antiaircraft machine gun nest atop the three-legged steel tower.

“When we got there, we found out that the four 50-caliber machine guns didn’t have any ammunition,” he said. “But before anybody could go below for ammunition, the ship blew up.”

A Japanese bomb sank the 1917-vintage battlewagon that the Navy modernized in 1931.

“The concussion tore most of our clothes off,” Vessels said. “But if we hadn’t been up in the mainmast, we wouldn’t have made it.”

From their lofty vantage point, Vessels and the other sailors watched helplessly as the enemy aviators bombed, torpedoed, and strafed the U.S. fleet. “The Japanese torpedo bombers came in barely above naval housing on the main island and would have to bank sharply to avoid hitting the Arizona,” he said.

“They came so close we could see the pilots thumb their noses at us. The rear gunners tried to machine gun us, but they couldn’t get their guns lowered enough, and the bullets whizzed over our heads.”

After the fires on the Arizona subsided, Vessels and the others came down from the mainmast. They were horrified by what they saw.

The forward part of their ship, blackened by fire and shrouded in choking, dark smoke, was a heap of twisted and broken steel. Vessels saw a dead officer on the searchlight deck—about halfway down the mainmast. The heat from the fires had curled back the soles of his shoes.

On the antiaircraft deck, he saw just one man standing, a sailor named Collins. He was so badly burned that Vessels recognized him only because he was tall.

Casualties on the Arizona included 1,117 dead out of a crew of 1,448, according to the National Park Service. Almost half of those killed in the attack were sailors and Marines on the Arizona, according to Day of Infamy by Walter Lord.

Besides the Arizona, seventeen ships were sunk or seriously damaged, and 188 Army Air Force and Navy planes were destroyed at their bases around Pearl Harbor and elsewhere on the island of Oahu, Lord added.

“That night we expected an attack by the Japanese army,” Vessels said. “We were prepared to go into the hills and fight it out if he had to.”

The attack did not come. The Japanese fleet, including the six aircraft carriers from which the enemy planes had taken off, was steaming away.

Vessels spent most of World War II in Pearl Harbor doing salvage work and helping man an honor guard that buried sailors and Marines killed in faraway island battles with names like Guadalcanal, Tarawa, Saipan, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa.

He said he didn’t hate the Japanese for almost killing him on Dec. 7, 1941. “I guess they were just following orders the same as we would have followed orders from our commander-in-chief.”

In 1971, Vessels, who was a member of the Pearl Harbor Survivors Association, returned to Hawaii and visited the gleaming white memorial that straddles the hull of the old ship, the outline of which is visible just below the water.

On one wall of the structure is a roll of the Arizona’s crew who died in the attack. The names include Gunner’s’ Mate Third Class Worth Ross Lightfoot, Vessels’ partner at acey-deucy.

Berry Craig of Mayfield is a professor emeritus of history from West Kentucky Community and Technical College in Paducah and the author of six books on Kentucky history, including True Tales of Old-Time Kentucky Politics: Bombast, Bourbon and Burgoo, Kentucky Confederates: Secession, Civil War, and the Jackson Purchase, and, with Dieter Ullrich, Unconditional Unionist: The Hazardous Life of Lucian Anderson, Kentucky Congressman. Reach him at bcraig8960@gmail.com