Every ten years, according to the United States Constitution, the census counts heads to come up with the number of Congressional representatives allotted to each state. Within this process, everyone counts, not just U.S. citizens. The idea is that a state’s political power reflects its population, not its wealth, and that power shifts every decade based on population changes.

In 2017, the League of Women Voters launched a comprehensive study of redistricting because of the crucial role it can play in civic engagement. The shape and geographic boundaries of districts — and the mix of people within a district — can make it easier or harder for regional voices to be heard and regional interests to be addressed.

Legislative districts are refashioned by redistricting commissions. Their composition varies from state to state, but they generally take one of two forms: a non-political commission whose members cannot hold political office or a political commission whose members can hold office.

Kentucky follows the “Let’s Make a Deal” model. Our revised legislative maps were configured behind Door #2 by the supermajority Republican legislature. Maps were released to the public on December 30, providing one holiday weekend for review. They were presented to the entire legislature on January 4, quickly approved, and then sent to Gov. Beshear on Jan. 8. The timetable did not allow for public forums, hearings, or rigorous analysis. Some critics say that detailed information on boundaries and key population information was not included, so the rationale for changes was not specified.

Despite the Kentucky Fair Maps Campaign, an initiative of the LWV, Kentucky’s redistricting process resisted efforts that would ensure transparency. When the League’s efforts to create a citizen-led redistricting advisory commission failed, they called for an open, transparent process with robust opportunities for public input. Statewide and regional Fair Maps Forums/Webinars were conducted in the fall of 2021 to share draft maps and gather public comments for legislators. The input was ignored and the resulting district configurations favor the interests of the Republican supermajority.

Murray State University’s Dr. William H. Mulligan, Professor Emeritus of History, described the partisan process as “distressing,” even while admitting that there has always been a little “fudging” with district lines.

“In the past,” he explained, “county lines were almost a sacred unit in redistricting.”

Not so in 2022. With such a substantial Republican majority in charge, “It eliminates any need to compromise,” Mulligan said. “That, historically, has been very dangerous.”

Calling the redistricting “political gerrymandering” designed to “dilute the voices of certain minority communities,” Kentucky’s Governor Beshear, a Democrat, vetoed it. Predictably, the legislature set the veto aside with an override. In response, the Kentucky Democratic Party filed a lawsuit with a group of Franklin County residents to challenge the newly configured districts.

According to KDP chair Colmon Elridge, “These maps were drawn behind closed doors with no public input to silence the voices of hundreds of thousands of Kentuckians. We are joining residents who are disenfranchised by these gerrymandered districts to stop this partisan power grab.”

In addition, he said, “These maps intentionally slice up cities and counties, reduce the number of women serving in the House and dilute the voices of minority communities.”

Republican Rep. Jerry Miller of Louisville, chief map drawer for the House, said, “We could’ve drawn this district or that district differently, but I assure you these maps fully meet our obligations to the law and the citizens of Kentucky.”

The changing boundaries stem from population changes reflected in the latest Census data, which indicate that eastern and western Kentucky generally lost population, while central and northern sections gained residents. The shape of new districts are consequential for candidates seeking office, and their constituents, in the coming decade. For instance, a Republican from Marion County, Lynn Bechler, voted “no” because he was drawn into another incumbent’s district in the new map.

The new shape of the first Congressional District extends deeper into central Kentucky to include Franklin and Washington Counties and part of Anderson County. Already a sprawl of a district, the 1st will – if the lawsuit does not prevent it from happening – stretch from the southwestern corner of Kentucky, Fulton County, lumbering along the border with Tennessee until it heads north in a jumble of counties and lands in Frankfort, about 300 miles away.

Republican senator Adrienne Southworth spoke out against the redistricting for putting her constituents in Franklin and Anderson counties into the same district as people living hundreds of miles away.

“This is the kind of thing that I believe we’re here to make sure doesn’t happen,” she said. “The fact that my constituents are now going to be represented as the same constituents from Fulton County makes zero sense to me.”

It is all the same to Rep. James Comer, the first district’s Congressional Representative, whose district now covers an even bigger area than before. With homes in Tompkinsville and Frankfort, chances of running into Rep. Comer at a ballgame in Murray, at church in Fulton, in a Hopkinsville grocery store, or even at one of his three regional offices is now slimmer than ever.

“But I’ll represent whatever the Kentucky General Assembly comes up with,” he said. “I’m happy to represent Frankfort.”

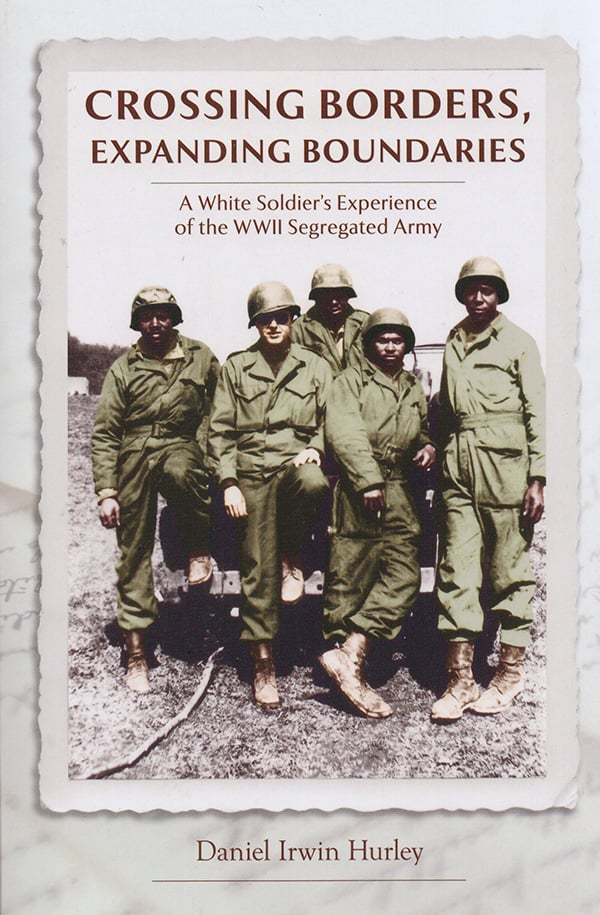

Note: The headline and image at the beginning of this article refers to the poem “Ozymandias,” by Percy Bysshe Shelley. Although written in 1817, the poem continues to be relevant in its theme, about the temporary nature of abuse of power against tougher forces.