By Paul A. Tenkotte

Special to the NKyTribune

It was Friday, March 5, 1964, and the weather was cold and rainy in Frankfort, the state capital of Kentucky. Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., Jackie Robinson, and the folk trio of Peter, Paul and Mary were among the thousands assembled for a civil rights march down Capitol Avenue.

The 1964 March on Frankfort was arranged by Frank L. Stanley, Jr. and the Allied Organizations for Civil Rights (AOCR) to encourage the Kentucky General Assembly to pass proposed legislation prohibiting discrimination in public accommodations. Governor Edward T. Breathitt (1963-67) did not attend the event, but his wife and daughter briefly did. Breathitt met privately with civil rights leaders that day. He promised his support, but a bill did not pass that session.

Two years later, the Civil Rights Act of 1966 passed the Kentucky General Assembly. Martin Luther King, Jr. praised it as “the strongest and most comprehensive civil rights bill passed by a southern state.”

Of course, it was debatable in 1966—as it is now—that Kentucky was truly a southern state. Rather, since before the Civil War and even today, it was and is a border or gateway state, greatly influenced by the more pro-business, Northern slant of places like Northern Kentucky.

In fact, a Northern Kentucky chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), joined by a Northern Kentucky branch of the NAACP, had achieved great success in desegregating public accommodations in our region before the March on Frankfort. Thanks to CORE, the NAACP, and local civil rights leaders like Alice Shimfessel (1901-83), Bertha Moore, Fermon Knox (1923-2001), Rev. Edgar Mack (1930-91) and others, Northern Kentucky was leading the state.

Northern Kentuckians were clearly in evidence that rainy day in March 1964 in Frankfort. Frankfort was then part of the Catholic Diocese of Covington. On behalf of the Diocese, Rev. Allen J. Meier (1920-2019) offered the invocation at the Capitol. There, Fr. Meier met Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., whom he described as “very sincere . . . the type of man you wanted to do what he wanted.”

Rev. Meier was a member of the Commission for Religion and Race, where he, Rev. Anthony Deye, and Rev. Paul Ciangetti attended monthly meetings at the Covington YMCA with area Protestant ministers in an effort to forward the cause of civil rights.

Drafted into military service in August 1943, Meier was selected for the Army Air Corps, and spent five months at Marietta College in Ohio in flight training. When the army realized that they were training too many pilots, he was transferred to gunnery school at Yuma, Arizona. Assigned to a crew in Lincoln, Nebraska, he received three months of further training at Pueblo, Colorado before shipping off to Europe. Serving in the 8th Air Force, 44th bomb group, 66th bomb squadron as a waist gunner, Meier flew 24 missions over enemy territory. On October 25, 1945, he was discharged from the army, and three weeks later, entered the seminary. The decision seemed natural for Meier. After VE Day, his squadron had flown at tree-top level over Germany. “There I saw the destruction and it was heartbreaking,” Meier recounted. “I figured I had to do something constructive with my life.”

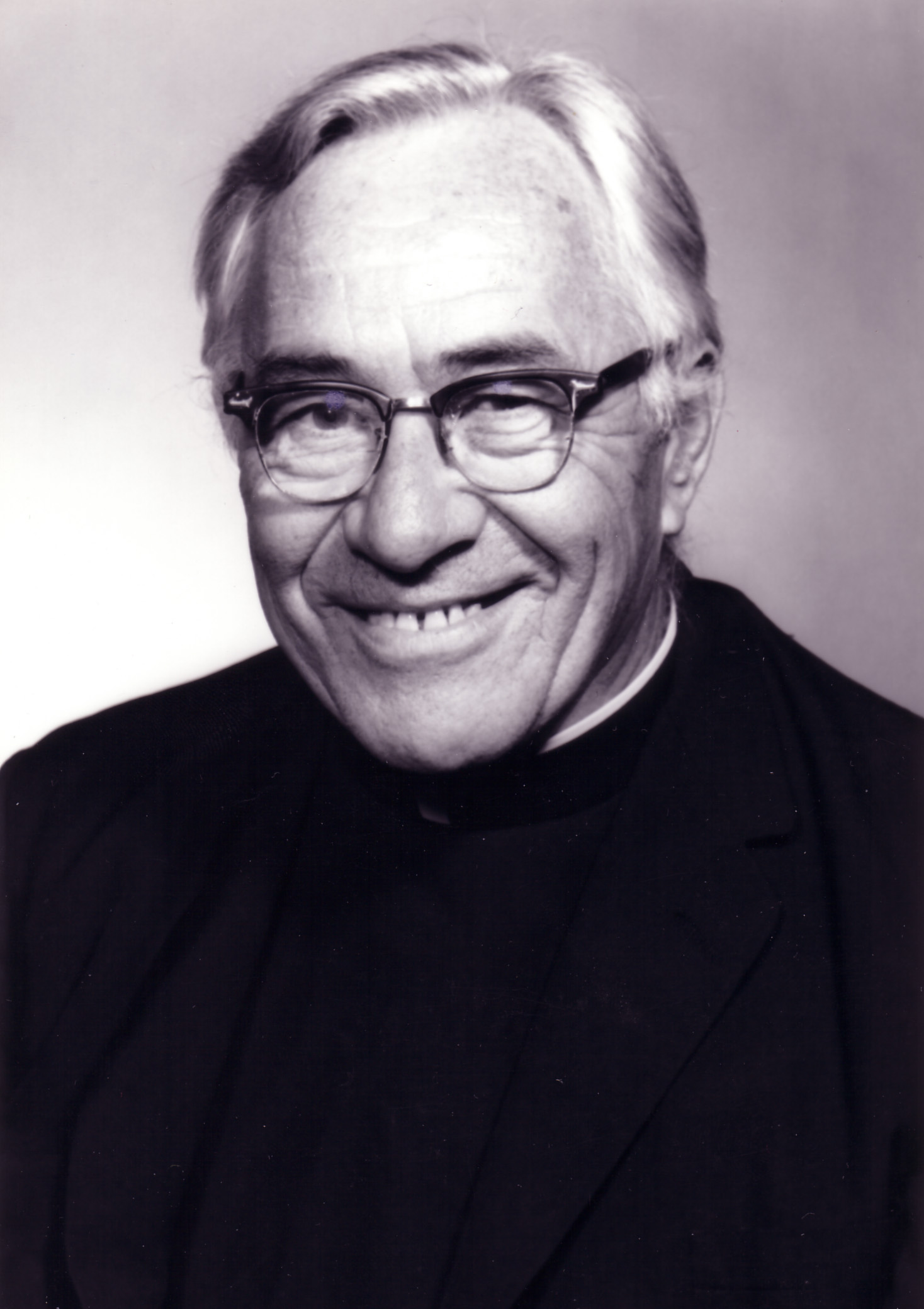

Even more familiar with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was Fr. Anthony Deye (1912-88). “Tony” Deye was one of seven children, raised on a farm on John’s Hill Road in Wilder, Kentucky. Widowed in 1919, his mother Elizabeth was a strong Catholic woman, a positive influence on his life and his decision to become a priest. Anthony studied at the Gregorian University in Rome. There, in the late 1930s, he had a vantage point to witness the hateful rhetoric and machinations of the fascist leaders Hitler and Mussolini. In 1938, upon his return to the United States, Fr. Deye was “determined to be a disciple of peace who would fight racism.”

Later earning a master’s degree in History from the University of Cincinnati and a doctorate in History from the University of Notre Dame, Deye served as academic dean and professor at Villa Madonna (now Thomas More) College. A longtime advocate of civil rights, he insisted upon the integration of the diocese’s Camp Marydale, and in the 1940s he coached basketball, baseball, and football teams at the African-American Our Savior School in Covington. In 1965, Fr. Deye met Martin Luther King, Jr., as a participant in King’s second Selma-to-Montgomery march. Fr. Deye spent his life fighting for civil rights and against injustice.

Fermon Knox was born in Dime Box, Texas and raised in Lee County, Texas. While serving four years in the Philippines during World War II, he contracted malaria. After the war, Knox attended Kentucky State College (University) in Frankfort, an historically black college, on a football scholarship.

In 1958, Knox’s employer, an insurance company, transferred him to the Cincinnati area. Living in Covington, he worked assiduously for the cause of Civil Rights, serving as president of the Northern Kentucky branch of the NAACP. Knox was instrumental in the desegregation of Covington’s public schools, and served as the first executive director of the Northern Kentucky Community Action Commission. He knew Martin Luther King, Jr., as well as Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth and many of the leading civil rights leaders of his day.

It never ceases to amaze me how the Greatest Generation, who fought the Great Depression and World War II—men like Meier, Deye, and Knox, and women like Alice Shimfessel and Bertha Moore—had a deep-seated compassion for others. They worked incessantly for equality. Their lives were living testimonies to the words of Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.: “The belief that God will do everything for man is as untenable as the belief that man can do everything for himself. It too, is based on a lack of faith. We must learn that to expect God to do everything while we do nothing is not faith, but superstition.”

We want to learn more about the history of your business, church, school, or organization in our region (Cincinnati, Northern Kentucky, and along the Ohio River). If you would like to share your rich history with others, please contact the editor of “Our Rich History,” Paul A. Tenkotte, at tenkottep@nku.edu. Paul A. Tenkotte, PhD is Professor of History at Northern Kentucky University (NKU) and the author of many books and articles.

See also:

Dorothy Day