By Howard Whiteman

Murray State University

As twilight shifted to first light, the sound of an awakening forest slowly started to grow subtle at first, and by the time dawn had broken they were in full force. The turkeys woke up first, and kept chattering for an hour as they flew down from the roost and began organizing the flock and their day. Other birds quickly chimed in, from hairy woodpeckers to blue jays. Once the crows started, I could barely hear anything else, they were so loud and raucous.

You would think that such an inspired wake up call, standing in my tree stand for the first time this season, would have helped re-indoctrinate me into the ways of the forest. It did not, and I failed miserably, moving too much.

Any movement at all is too much for turkeys, and one let me know it, incessantly calling putt-putt-putt to warn her comrades.

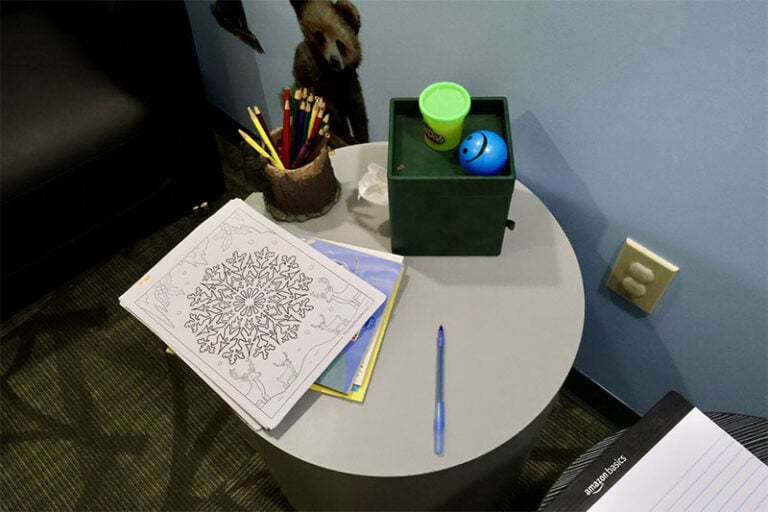

(Photo courtesy of Pxhere and is in the public domain.)

I’d like to think I was better by the afternoon, but I managed to move too much then too, raising the ire of an approaching doe and my wiggling being rewarded by her never-ending snorts. Warning calls from deer, turkeys, and other species have one thing in common – they often don’t stop.

It took a few more trips for me to get back into the rhythm of the forest, and to become one with it enough that none of its inhabitants saw, smelled, or heard me before I wanted them too. I knew it would happen, because I have passed that exam many times before, but each fall is a new test after a long summer of being out of practice. And the only way to practice is to actually be in the woods.

When you become one with the forest, you experience so much more than the trees.

Even with my bad hearing, I notice the difference between the soft steps of an approaching deer and the rambunctious hopping of a gray squirrel. Every sound gets checked out, not with a jerk of my head but with a slight, imperceptible shift, making sure I am not revealed. Although our sense of smell is our weakest sense, even the odors come alive, particularly after a rain, and occasionally you can sniff the strong odor of a rutting buck.

My eyes seek out movement in the trees and reveal a snoozing barred owl, a red- shouldered hawk peering at a nearby squirrel, or a brown creeper looking for insects under tree bark. Sometimes all of that motionless waiting leads to a coyote, fox, or bobcat, some of the wariest creatures in the forest.

Wild turkeys, though, are the real test. Turkeys have excellent color vision and even the slightest movement that is out of place with nature is suspect. They also have amazing ears, and once they hear an out of place sound, they put a laser focus on the spot with their eyes. Their patience is next. Turkeys don’t care how long they have to wait, if they think something is amiss, they are going to stare you down until they figure it out. Of all the creatures in the forest, turkeys are the final exam in becoming part of it. When a flock passes by me without noticing, it’s my A+.

You don’t have to be a hunter or even be close to a forest to become one with nature for a while. A city park often has enough nature that is a bit easier for it to acclimate to our presence. Your backyard will do as well. Have a seat by a tree and just sit still. Move little, don’t make noises, and soak in the sounds, smells, and sights of

nature. Once you become one, with a squirrel, bird, or insect coming right up to you, you’ll want to go back again and again.

Even those of us who don’t spend any time in the woods have to learn how to adapt to a new environment. All kinds of things affect us every day, and sometime our sense of reality is turned upside down. But in each of these cases, the lessons from the forest can help us as well.

Sometimes we need to slow down, stop thinking for a while, and just figure out our surroundings. Whether that is the forest, a new job or classroom, a new friend, or a new reality, it all requires us to be patient, still for a while, and be attentive.

Humans are a very adaptable species, and maybe the lessons we learn from the forest can help all of us get along better in the rest of our lives.

I know that time in the forest is good for my soul, and learning to make turkeys and deer think I don’t exist has allowed me to blend in to other, human-dominated surroundings. I carry a little bit of that forest knowledge everywhere I go, and use those same skills to deal with everyday life. Perhaps some practice in a nearby forest or your backyard will help you as well. Either way, may the forest be with you. Always.