(Editor’s note: We’re celebrating ten years of Our Rich History! You can browse and read any of the past columns, from the present all the way back to our start on May 6, 2015, at our newly updated database here.)

By John Schlipp

Special to NKyTribune

The Ohio River has long been more than a geographical boundary — it’s been a musical artery, pulsing with rhythm and song.

Flowing between Cincinnati and Northern Kentucky, the mighty waterway served as a cultural crossroads, carrying musicians, traditions, and innovations that helped shape the region’s rich musical legacy.

From legendary rhythm and blues musicians such as the Isley Brothers and Bootsy Collins to renowned “Great American Songbook” vocalists such as Rosemary Clooney and Doris Day, the region has boasted more than its share of noted musical artists. Today, festivals like America’s River Roots celebrate our regional heritage, reminding us that the river’s influence on music is as deep as its current.

Musical encounters along the riverbanks

In the 1800s, the Ohio River was a gateway to the West, bringing together African Americans, Germans, Irish, and other cultures whose musical traditions mingled in towns, churches, and on the riverbanks. Before that, Native Americans enjoyed the music of drums, cane flutes, and gourd rattles. Early music was often improvised or passed down through family gatherings. Fiddlers, flutists, and singers shared “Old World” tunes and crafted new compositions inspired by frontier life.

One such moment was documented in 1811 when British traveler John Melish stayed in Covington at Thomas Kennedy’s house (demolished; now George Rogers Clark Park on Riverside Drive). There, travelers heard Kennedy, a proud Scots-Irishman, play “Rothermurche’s Rant” in the Highland style on the fiddle—an early example of cultural exchange along the river.

Riverbanks and roustabouts

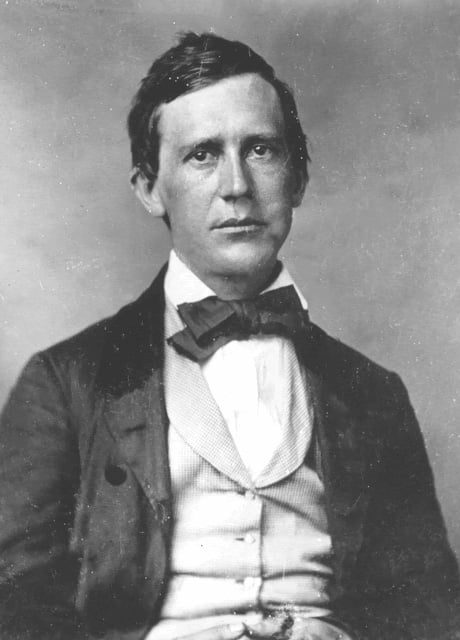

Stephen Collins Foster, often called the father of American popular music, worked in Cincinnati during the 1840s. His exposure to riverbank life and the music of free Black laborers carrying cotton bales from steamboats on the Cincinnati docks deeply influenced his compositions.

Songs like “Oh! Susanna” and “Nelly Was a Lady” reflect both minstrel rhythms and a growing empathy for the African-American experience. Foster was among the earliest genuinely American composers. In theme, his songs were distinctly American, not merely imitations of English and German music of his time.

Stephen Foster’s songs sentimentalized and promoted the peak of showboats and river culture. Melodrama and vaudeville acts, similar to those depicted in the famous “Showboat” musical play of 1927 (its libretto now in the public domain), prevailed. Interestingly, the showboat “Majestic,” which was permanently docked at its Ohio River wharf in Cincinnati, was among the last of the original showboats featuring live entertainment in the region.

Fusion of ethnic and vernacular traditions

The Ohio River was a place where Black and White laborers worked, sang, and danced together. This fusion birthed uniquely American genres—spirituals, blues, gospel, and ragtimeb — alongside German folk songs and Catholic liturgical music. Cincinnati’s harbor became a melting pot of Southern soul, Western energy, and Northern innovation.

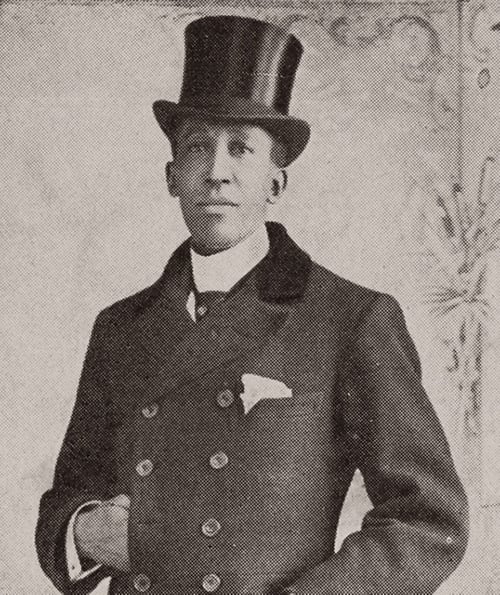

Sam Lucas, a mid-19th-century Cincinnati barber turned minstrel star, was a pioneering African-American performer whose career bridged minstrelsy, vaudeville, and early Black musical theater. Rooted in the vibrant barbershop quartet culture of Cincinnati’s Black community, Lucas helped blend spirituals with popular performance styles — laying the groundwork for iconic 20th-century vocal groups like the Mills Brothers and the Ink Spots. His rise to national fame carried the diverse sounds of the Ohio River region into the foundation of American popular music.

German Saengerfests and singing societies flourished, while African-American spirituals echoed through African Methodist Episcopal Churches and riverfront gatherings. The African spirituals enriched the local soundscape alongside German and Catholic influences, laying the groundwork for uniquely American genres like gospel and blues. The Fisk Jubilee Singers, who toured the North in the 1870s, performed in Cincinnati, introducing mainstream audiences to the power and beauty of classic spirituals.

Broadcasting and recording: Amplifying river sounds

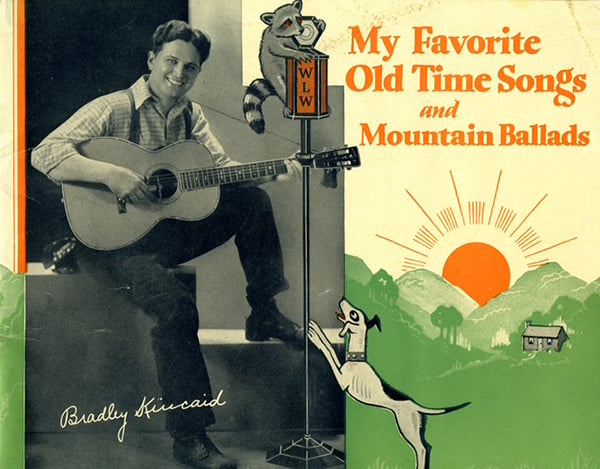

Cincinnati and Northern Kentucky became hubs for recording and broadcasting. Powel Crosley’s WLW radio, on the air in 1922 and known as “The Nation’s Station,” launched the careers of artists like the Clooney Sisters (Betty and Rosemary), Fats Waller, Kenny Price, the Mills Brothers, and others.

Earlier, the Ohio Phonograph Company, founded in Cincinnati in 1888, was among the first to record regional music — capturing minstrel tunes, German yodels, sentimental ballads, religious hymns, waltzes, marches, polkas, and opera selections.

Gennett Records — just northwest of Cincinnati — played a pivotal role in transforming the Ohio River region’s grassroots music into nationally influential sounds. Gennett Records operated from 1917 to 1934. A division of the Starr Piano Company in Richmond, Indiana, it was widely recognized as an early, influential independent record label in American music history. Gennett recorded a wide range of genres—including jazz, blues, gospel, country, and early popular music—and helped launch the careers of legendary artists like Louis Armstrong, Jelly Roll Morton, and Hoagy Carmichael.

Bradley Kincaid, a beloved WLW country music star of the 1920s, helped bring Appalachian ballads to national audiences and recorded several of his early hits at Gennett Records — bridging Cincinnati’s river-roots traditions with America’s growing country music scene.

WLW in Cincinnati was instrumental in the birth and early success of King Records during the 1940s, supplying a steady flow of country talent from its popular live broadcasts, such as those featuring Grandpa Jones and Merle Travis.

King Records’ founder, Syd Nathan, capitalized on the region’s unique musical landscape, where Appalachian migrants and Black southerners alike brought their own traditions to the city’s recording studios and airwaves, laying the groundwork for country, and rhythm & blues (R&B) genres to flourish together.

Many of the session musicians who played regularly on WLW radio shows would also moonlight at King’s Brewster Avenue studio in Cincinnati, providing backup for both country crooners and pioneering R&B artists. This cross-pollination of musical styles resulted in an innovative studio culture where the backup bands could record the same songs for acts as diverse as the Delmore Brothers (country) and Wynonie Harris (R&B), helping King Records bridge racial divides and influence the birth of rock and roll.

Musical artists like the “Godfather of Soul” James Brown, Bonnie Lou, the Swan Silvertones, and Otis Williams and the Charms found their voices in the Cincinnati region, blending river-rooted traditions into nationally influential sounds. The collaborative spirit between WLW and King Records not only fueled a local creative explosion but also shaped the course of American popular music for decades to come.

Legacy and celebration

From barbershop harmonies to bluegrass, from gospel choirs to jazz musicians, the Ohio River’s musical legacy continues to resonate. Events like the 2025 America’s River Roots Festival, onsite venues like the Cincinnati Black Music Walk of Fame, and programming on local radio stations, such as WMKV and WGUC, honor this heritage, showcasing how river culture fostered innovation, collaboration, and genre-mixing.

As conductor John Morris Russell of the Cincinnati Pops once said, “The music experience of Cincinnati is the music experience of America, and it starts with Stephen Foster.” The Ohio River didn’t just carry goods—it carried melodies, memories, and the soul of a region that still sings today.

This article is a summary of John Schlipp’s comprehensive three-part series published in the “Northern Kentucky Heritage” magazine:

John Schlipp, “Music in Northern Kentucky and Cincinnati: Part One: Rolling Along a River of Song,” “Northern Kentucky Heritage,” 27 (2), Spring-Summer 2020.

John Schlipp, “Music in Northern Kentucky and Cincinnati: Part 2: River Cities’ Regional Roots—The African American Legacy from Ragtime to Bluegrass to Jazz and Gospel,” “Northern Kentucky Heritage,” 28 (1) Fall-Winter 2020.

John Schlipp, “Music in Northern Kentucky and Cincinnati: Part 3, Cincinnati’s Country, Soul, and Media Legacies Resonate Worldwide,” “Northern Kentucky Heritage,” 29 (1) Fall-Winter 2021.

John Schlipp is a Career Navigator Librarian at Kenton County Public Library specializing in business resources and intellectual property awareness. He is a member of the Patent and Trademark Resource Center Association, and can be contacted at john.schlipp@kentonlibrary.org.

Paul A. Tenkotte, PhD is Editor of the “Our Rich History” weekly series and Professor of History at Northern Kentucky University (NKU). Browse ten years of past columns here. Tenkotte also serves as Director of the ORVILLE Project (Ohio River Valley Innovation Library and Learning Engagement). For more information see orvillelearning.org. He can be contacted at tenkottep@nku.edu.