The riverboat captain is a storyteller. Captain Don Sanders shares the stories of his long association with the river — from discovery to a way of love and life. This a part of a long and continuing story.

By Capt. Don Sanders

Special to NKyTribune

Everything happening on the river is not necessarily something new. Quite often, I receive reminders of past reflections of river days gone by.

Just several days ago, when the phone rang, an unknown number appeared on the screen. Usually, I let unlisted calls go to voicemail, but I felt an urge to answer the caller. After verifying that I was the correct person, the caller sought to speak to me as quickly as possible.

I am, as the gentleman on the other end of the conversation, who identified himself as Clarance Merk, had hoped, one of only a few known survivers who witnessed the remains of the steamboat ALICE DEAN, sunk by the Confederate Raider, Gen. John Hunt Morgan in 1863, being removed, in kindling wood-sized pieces, from the Ohio River by a crane-operated clamshell bucket during the summer of 1965. The older I become, the more I’m tagged “the last remaining,” or the “sole-surviving,” whoever or whatever. It’s really not a distinction to take pride in other than it’s a reminder that I’m still on the sunny side of the sod.

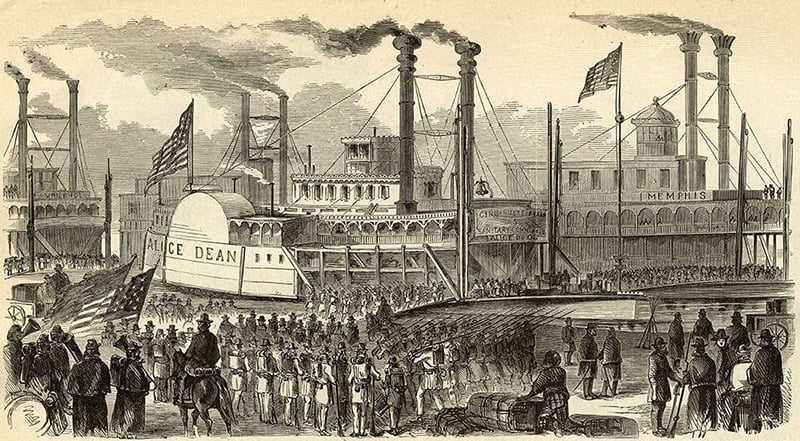

The unfortunate ALICE DEAN, a small, yet elegant, sidewheel packet, built in Cincinnati in 1863, was underway in the vicinity of Brandenburg, Kentucky, on that July day in the third year of the War Between the States, when General Morgan’s command captured the ALICE DEAN and pressed the newly built boat into ferry service, transferring Morgan’s Raiders from the Brandenburg side of the river to the Indiana shore.

After the DEAN fulfilled her involuntary commitment, the Raiders burned her. Whatever remained of the ALICE DEAN sank beneath the waves. Over the century before I saw her brightly, white-painted wooden remains stacked high on a deck barge, local “raiders” picked over her bones whenever low river stages allowed such incursions. A year after the DEAN went down, her engines and other mechanical fittings were salvaged and used again on other steamboats.

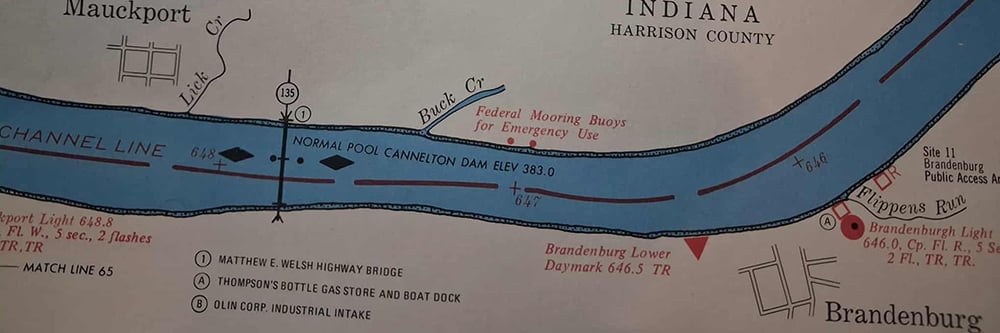

During the summer of 1965, I was a recent graduate of Eastern Kentucky University, and working aboard the Steamer DELTA QUEEN before enlisting in the U. S. Air Force later that year. Around 45 miles below Louisville’s McAlpine Lock & Dam, the QUEEN approached the worksite of a new bridge under construction spanning the Ohio River between Brandenburg and Mauckport, Indiana.

Captain Ernest E. Wagner alerted me to the activity above the construction site. Close to the shore, a floating crane was seen busily digging brightly-painted white pieces of what appeared to be large chunks of kindlingwood from beneath the river with a clamshell bucket. Piled high on a flat deck barge, at least 15 to 20 feet in height, was a pile of amazingly brilliantly white-painted chunks of splinter-like wood.

As I watched in wonder at the unusual activity, word came from the pilothouse that what was transpiring as the DELTA QUEEN paddled by was the removal of the wreck of the hapless ALICE DEAN, burned and sunk there a century earlier. The impression of that day burned into my brain with the brilliance of the white wooden remains of a wartime relic of that violent time in July of 1863. In the 60-plus years since I passed the wreck site of the DEAN, I always recall seeing the “bones” of the ALICE DEAN piled high on that work flat. The last time I passed was aboard the CLYDE in 2012.

Later, a business card I made of the CLYDE landed in a park on the Kentucky shore above the bridge, now named the Mathew E. Welsh Bridge, which always reminds me of the day I witnessed the remains of the ALICE DEAN stacked glistening in the sun as the DELTA QUEEN eased reverently by.

During a follow-up call with Clarence Merk, he revealed the latest development in the ALICE DEAN saga: the possibility of mapping the debris field of the wreck to show the location of any possible remains of the steamboat. Clarence mentioned the side paddlewheels as a potential reminder of a once-elegant steamboat built for speed and elegance.

Clarence also said that before the construction of the wicket-style dams and locks on the Ohio River, local scavengers had access to the remains of the DEAN, especially during periods of low water. However, after the 1929 canalization of the river, the bones of ALICE DEAN lay submerged in deep water until a dam-site problem in 1959 drained the river in the vicinity of the remains. The low-water incident enabled the reestablishment of the DEAN’s location after 30 years during which it lay forgotten.

Mr. Merk disclosed that when I witnessed the clamshelling of the wooden remains of the ALICE DEAN onto a deck barge in July of 1965, it was at the time certain Indiana activists bribed the crane operator working on the construction of the bridge to dig out what amounted to eight dump truck loads of debris from the ill-fated steamboat. Supposedly, those behind the clamshell caper used the salvaged wood to fabricate memorabilia from the DEAN. However, I expressed doubt that such a quantity — essentially a massive mountain of splinters — actually found reuse as mementoes of the once-elegant Cincinnati steamboat.

What lies ahead for the “bones” of the ALICE DEAN after mapping the underwater site of the wreck area, according to Mr. Merk, is an application to the National Registry of Historic Places to get the site onto the National Register, the official government list of the nation’s historic places worthy of preservation. The Steamer DELTA QUEEN, for example, is a maritime member of the Registry.

After inclusion on the National Register, Clarence hopes that the U.S. Park Service and the United States Navy assume an ownership role in the nautical battlefield remains of the civilian vessel that haplessly found itself in the middle of a legendary, though ill-fated, episode of the American Civil War.

Although the outcome concerning the mostly forgotten remains of the ALICE DEAN may take years far beyond my allotted time remaining on this planet to accomplish, whatever happens, the bones of the once lovely steamboat lady lie deep in the waters of the Ohio River, resting without a care in the world.

Captain Don Sanders is a river man. He has been a riverboat captain with the Delta Queen Steamboat Company and with Rising Star Casino. He learned to fly an airplane before he learned to drive a “machine” and became a captain in the USAF. He is an adventurer, a historian and a storyteller. Now, he is a columnist for the NKyTribune, sharing his stories of growing up in Covington and his stories of the river. Hang on for the ride — the river never looked so good.

Captain Don Sanders is a river man. He has been a riverboat captain with the Delta Queen Steamboat Company and with Rising Star Casino. He learned to fly an airplane before he learned to drive a “machine” and became a captain in the USAF. He is an adventurer, a historian and a storyteller. Now, he is a columnist for the NKyTribune, sharing his stories of growing up in Covington and his stories of the river. Hang on for the ride — the river never looked so good.

Purchase Captain Don Sanders’ The River book

Capt. Don Sanders The River: River Rat to steamboatman, riding ‘magic river spell’ to 65-year adventure is now available for $29.95 plus handling and applicable taxes. This beautiful, hardback, published by the Northern Kentucky Tribune, is 264-pages of riveting storytelling, replete with hundreds of pictures from Capt. Don’s collection — and reflects his meticulous journaling, unmatched storytelling, and his appreciation for detail. This historically significant book is perfect for the collections of every devotee of the river.

You may purchase your book by mail from the Northern Kentucky Tribune — or you may find the book for sale at all Roebling Books locations and at the Behringer Crawford Museum and the St. Elizabeth Healthcare gift shops.

Click here to order your Captain Don Sanders’ ‘The River’ now.