By John Schlipp

Special to NKyTribune

As the holiday season sparkles across Cincinnati and Northern Kentucky, it’s worth remembering that this region has long been a cradle of creativity — where artistry and innovation have shaped traditions celebrated around the globe. From legendary inventors to iconic toys, our Tri-State region’s influence on holiday traditions runs deep.

Cincinnati’s reputation for ingenuity is more than civic pride — it’s a legacy etched into everyday life. The region gave birth to toys that delighted generations. These innovations didn’t just fill stockings; they transformed toys and play throughout the world.

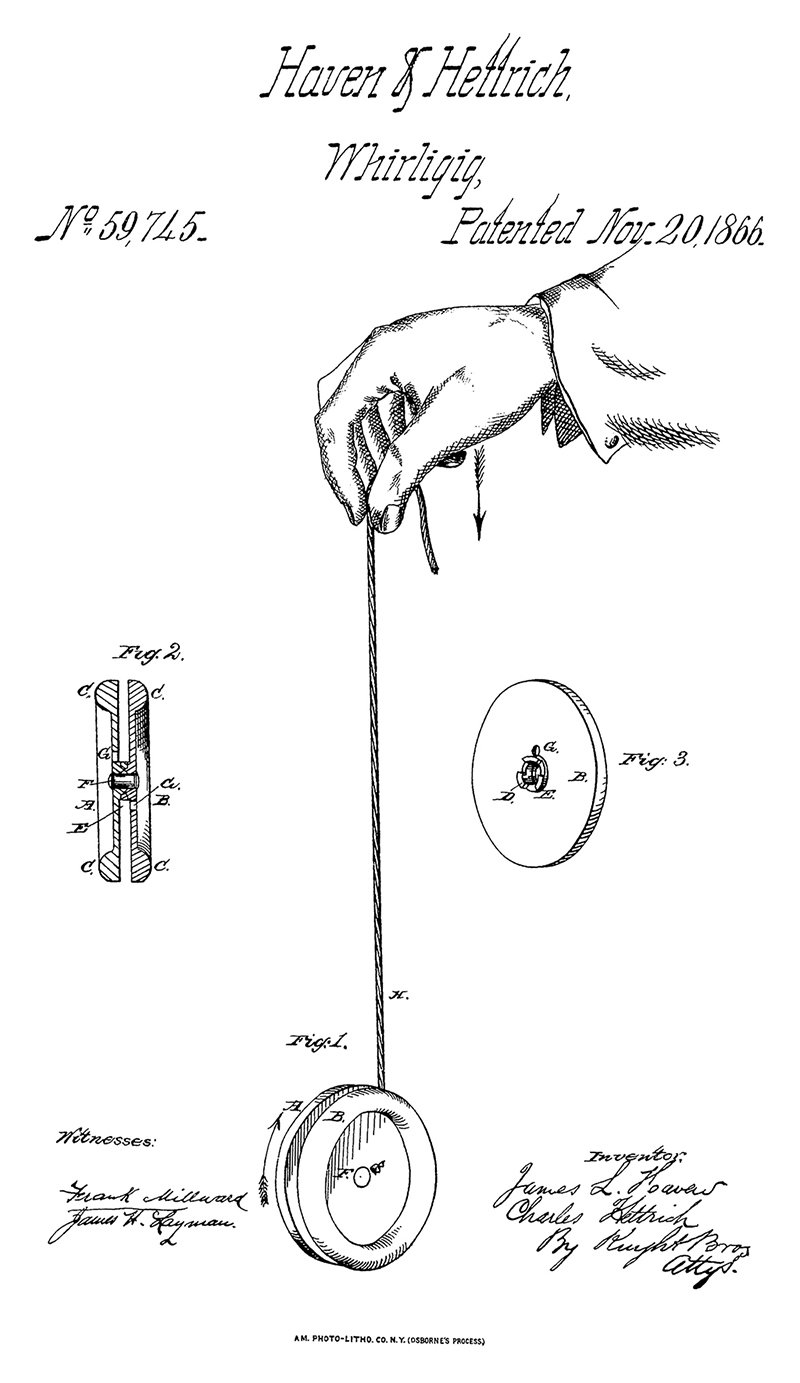

As families gather around the Christmas tree and children rush to open their presents this year, chances are high that a piece of Cincinnati and Northern Kentucky ingenuity is tucked inside the wrapping paper. From the U.S.-patent 59,745 “whirligig” — the first patented yo-yo invented by James L. Haven and Charles Hettrick in 1866 — to Kenner’s iconic Easy-Bake Oven that brought baking to generations of kids, the Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky region has a long, surprising history of inventing toys that define American childhoods.

Play-Doh is a timeless toy, invented in Cincinnati by Noah McVicker. It was originally marketed as a non-toxic wallpaper cleaner to remove coal-heat soot left on the walls of homes. However, as gas home heating became common, the demand decreased. Its potential as a toy was recognized by a regional nursery schoolteacher as she shared leftovers with her class. Soon, bright colors were added, and a new brand name was assigned by McVicker’s nephew. Today, millions of cans of Play-Doh are sold globally.

In 1971, Merle Robbins, a barber from Milford (east Cincinnati), invented the UNO card game to settle a family argument over the rules of Crazy Eights. Robbins and his family designed their first set of cards on their family dining room table. Taking their family savings of $8,000, they made 5,000 UNO decks of cards, selling these at their barbershop. Soon, his invention was licensed to International Games Inc., which was later acquired by Mattel.

Kenner, Jim Swearingen, and Star Wars

Kenner, founded in 1947 in Cincinnati, became a household name with toys that defined childhood memories. It was a global force in the toy industry thanks to its groundbreaking partnership with the blockbuster movie “Star Wars” and its sequels. At a time when movie tie-in merchandise was considered risky, Kenner’s design team — led by Jim Swearingen — saw the potential in George Lucas’ space saga. Swearingen, a University of Cincinnati graduate and sci-fi enthusiast, famously told his boss after reading the script, “We have to do this. We have to make these toys” (John Bach, “DAAP Alum Designed Original ‘Star Wars’ Toys,’ “UC Magazine,” June 2007).

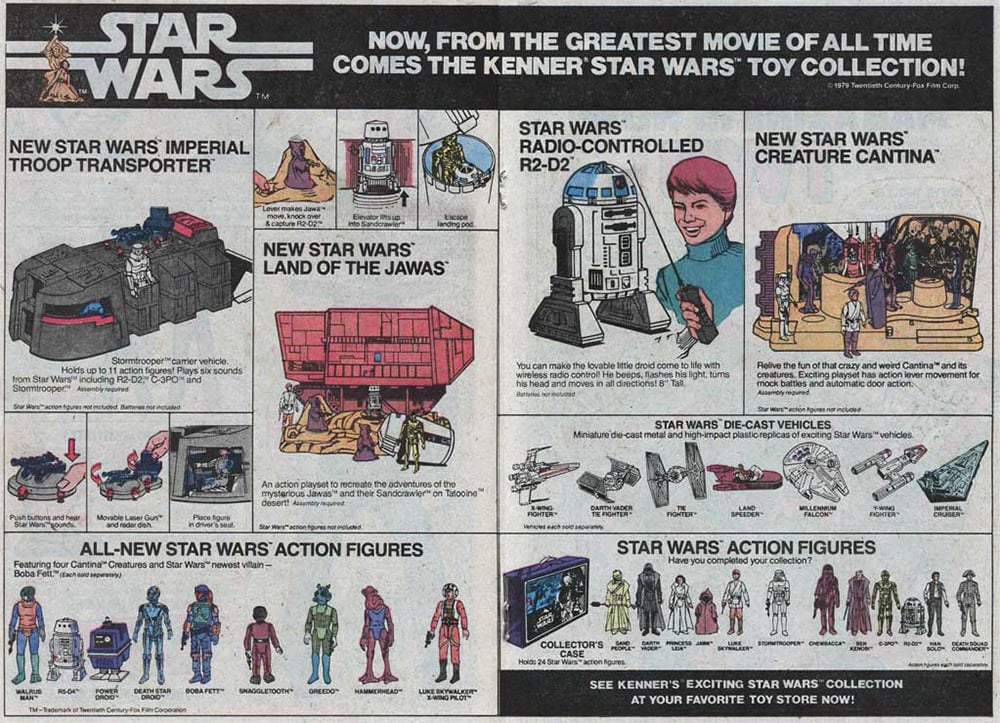

That conviction led to the creation of the now-iconic 3¾-inch action figure characters, a radical departure from the foot-long dolls of the era. This innovation allowed Kenner to produce entire sci-fi worlds — figures, vehicles, and playsets — that fit together seamlessly, forever changing the scale and scope of action figures in the toy industry. Swearingen’s innovative toys didn’t just replicate the science fantasy films — they invited children to live in their universe, sparking imaginative play that mirrored cinematic storytelling.

The toys that changed play: How Kenner turned Star Wars into a galactic phenomenon

When “Star Wars” blasted onto movie screens in 1977, it didn’t just redefine cinema—it sparked a revolution in the toy industry. Children everywhere wanted to bring the galaxy home, and Kenner Toys in Cincinnati answered the call. From 1978 to 1985, Kenner produced hundreds of different action figures, vehicles, and playsets inspired by “Star Wars,” “The Empire Strikes Back,” and “Return of the Jedi.” These toys became as iconic as the films themselves, cementing Kenner’s place in pop culture history.

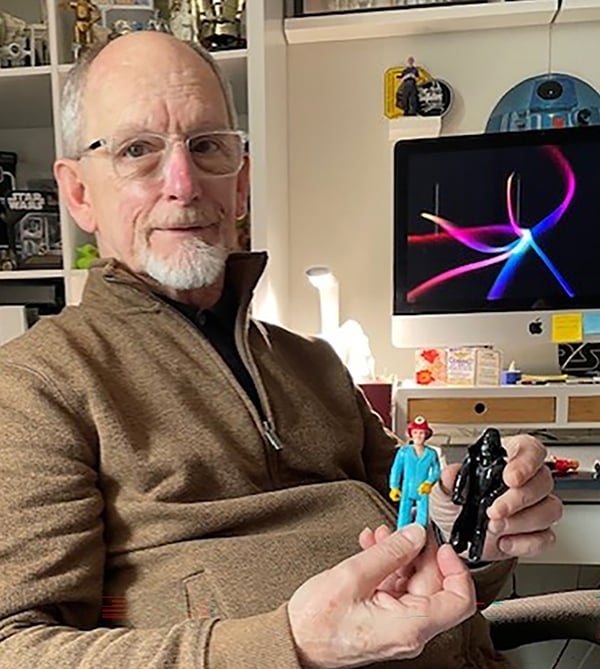

At the heart of this success was industrial designer Jim Swearingen, whose vision shaped the look and feel of the Star Wars toy line. Swearingen recalls first reading the script in early 1977 and being captivated by the dogfights between X-Wings and TIE Fighters. “I always tried to put myself in the shoes of a seven-year-old boy,” Swearingen said. “The ships were the heroes. The figures were the supporting cast” (Interview of Jim Swearingen by John Schlipp and Paul A. Tenkotte, December 13, 2025, Covington, Kentucky).

That insight drove the decision to create vehicles large enough for kids to handle, paired with figures scaled to fit inside — ultimately leading to the now-standard 3¾-inch action figure.

But design alone didn’t guarantee success. Enter Bernie Loomis, Kenner’s president and a former Mattel executive. Loomis championed the licensing deal with Lucasfilm and gave Swearingen’s team the freedom to innovate. He famously insisted the figures be “this big,” gesturing with his fingers — a moment that helped define the scale of action figures for decades. Loomis also pushed for “Toyetic” qualities, emphasizing play value and imaginative engagement. His leadership, combined with Swearingen’s creativity, turned a risky movie tie-in into a multi-million-dollar franchise.

Swearingen’s early prototypes were crafted from Fisher-Price Adventure People, modified with body putty and an X-Acto knife. These mock-ups, along with blueprints and concept art from Lucasfilm, laid the foundation for a toy line that would dominate store shelves and childhood memories. “We were fighting uphill,” Swearingen admitted, noting skepticism in the industry. “Star Wars was [then] a one-movie gamble, and nothing like that had ever been done before” (Interview).

From Cincinnati conference rooms to Hollywood backlots, the collaboration between Kenner and Lucasfilm created more than toys — it built a universe kids could hold in their hands. Today, those original figures and ships remain treasured collectibles, reminders of a time when imagination and innovation launched a galaxy far, far away into living rooms across America.

Challenges and setbacks

Jim Swearingen, along with his boss Dave Okada and Kenner executive Bernie Loomis, encountered challenges and setbacks in the introduction of the iconic Star Wars toys at Kenner in Cincinnati. Kenner’s work on the first “Star Wars” toys moved at high speed under tight time constraints, and the biggest early challenge was simply getting information. Swearingen, the principal conceptual designer in preliminary design, served as Kenner’s day‑to‑day liaison with Lucasfilm, fielding every request for photos, character views, and visual references. As he recalls, “early on, the biggest setback was, or the thing that slowed things down the most was getting information … getting the details on things.” Lucasfilm remained cautious about revealing too much, especially later films, even though the toy team needed clear front‑and‑back views of every character to move quickly.

Once Lucasfilm turned over materials, the bottlenecks shifted to Kenner’s internal processes. Sculptors needed weeks to complete a single 3 ¾‑inch figure in wax before it could be molded, cast, and handed off to mold makers, and Swearingen found himself constantly trying to pull timelines forward to meet aggressive dates. He notes that “the toy designers … they’re at a year and a half [out] … already working on it before the movie comes out,” describing how development cycles had to start long before audiences ever saw a frame on screen. In 1977, Kenner was compressing what was normally an 18‑ to 24‑month development cycle while working on an unknown film that was about to become a cultural phenomenon.

Licensing and approvals added a further layer of complexity. Kenner president Bernie Loomis negotiated the initial deal with 20th Century Fox and Lucasfilm, at a time when movies were generally considered poor toy licenses, while Kenner’s in-house licensing attorney Jim Kipling worked with lawyers at Lucasfilm and 20th Century Fox to finalize contracts and rights. Swearingen emphasizes that Loomis was not involved in day‑to‑day processes but set the overall direction and pushed Kenner to move quickly once the potential of “Star Wars” became clear. At the same time, George Lucas retained final approval over the look of the toys, which meant delays and revisions were always a risk as artwork and models moved back and forth between Cincinnati and California.

The most visible “setback” was what Kenner had already expected. It simply could not get finished toys onto store shelves by Christmas 1977. Swearingen explains that “we knew we couldn’t get any hard product out,” so at best they were aiming for early spring 1978 for actual figures. Out of that timing failure came the now‑legendary “Early Bird” certificate package: instead of action figures, parents bought a colorful cardboard kit and a promise that their children would be among the first to receive figures in the mail the following year. Swearingen calls the promotion “a coup that no one would have imagined before that,” because the “outrageous” idea of selling toys that did not yet exist generated enormous free publicity and turned an internal scheduling crisis into a marketing breakthrough that reshaped expectations for movie‑based toy lines.

Celebrations and milestones

Jim Swearingen’s favorite milestones with the “Star Wars” toys came late in his career, when he began appearing as a guest at fan conventions, starting with an unboxing‑themed toy convention in Mexico City in 2014. There he saw firsthand how a new generation of collectors, many of them inspired by documentaries about the original Kenner line, treated his work with the same reverence as the movies themselves. He also vividly recalls the thrill when the first figures finally hit stores, with kids and adults rifling through freshly opened shipping cases on the floor before toys even made it onto the pegs, and collectors already obsessing over details like “unpunched” hanging tabs.

Over time, Swearingen has watched the line evolve into something often aimed more at adults than children, with many parents who grew up with the toys passing their enthusiasm on to their kids. He treasures convention images of multi‑generational cosplay, such as a grandmother and granddaughter both dressed as Princess Leia. He also remembers a fan in Chicago who built a Boba Fett costume to mimic the rigid stance and proportions of the original Kenner figure, moving and posing as if he were the toy itself, a moment that underscored how deeply those early designs have embedded themselves in popular culture.

The legacy of Jim Swearingen and Kenner Toys endures because their innovations transcended a single franchise. While Star Wars was the crown jewel, Swearingen also contributed to beloved Strawberry Shortcake toys through a groundbreaking licensing partnership between Kenner and American Greetings. This collaboration marked a new era in toy marketing, turning a greeting card character into a multimedia phenomenon supported by television specials, cross-category merchandise, and an enterprising advertising campaign. According to Funding Universe, this strategy generated over $500 million in retail sales combined for American Greetings and Kenner in its first year, demonstrating how licensing can amplify cultural reach beyond the toy aisle (“American Greetings Corporation History,” “Funding Universe,”).

Swearingen’s work confirms that toys can be more than products — they can be cultural touchstones. Today, collectors treasure Kenner originals as artifacts of a creative revolution, and Swearingen (now residing in Northern Kentucky) remains celebrated at conventions and panels for shaping not only the Star Wars galaxy but the entire toy industry. His story is a testament to how imagination, risk-taking, and design ingenuity can create phenomena that span generations.

John Schlipp is a Career Navigator Librarian at Kenton County Public Library specializing in business resources and intellectual property awareness. Whether you’re inspired by famous inventors or musicians from our region, it is a powerful reminder that every great idea or creative work starts with a bold idea—and the right support. Kenton County Public Library offers stories and solutions for entrepreneurs and small business start-ups. Contact John at john.schlipp@kentonlibrary.org.

Paul A. Tenkotte, PhD is Editor of the “Our Rich History” weekly series and Professor of History at Northern Kentucky University (NKU). To browse more than ten years of past columns, visit: nkytribune.com/our-rich-history. Tenkotte also serves as Director of the ORVILLE Project (Ohio River Valley Innovation Library and Learning Engagement). He can be contacted at tenkottep@nku.edu.