The riverboat captain is a storyteller, and Captain Don Sanders will be sharing the stories of his long association with the river — from discovery to a way of love and life. This a part of a long and continuing story. This column first appeared in October, 2018.

By Capt. Don Sanders

Special to NKyTribune

After we reassembled on deck, Captain John Beatty faced-up to the BIG JOHN steam-powered crane and an empty hopper barge and shoved the small tow upstream above the sunken wrecks. Skillfully, he turned around and began easing slowly downstream in the swift current to position the crane in close to one of the sinkers. Two other coal hoppers beneath the water lay close within the pile of wrecks. Captain John promised us that once the crane was in position, we crewmen could have the rest of the day off and go ashore if we wanted.

Gingerly, the veteran pilot maneuvered the elder steam crane, floating on a riveted hull, into an underwater maze of twisted steel, when suddenly, a faint almost imperceptible shutter shook the deck beneath my feet.

Captain Beatty immediately started cursing and screaming:

“WE HIT THE *%#@ WRECK! CHECK THE *%#@ BILGES! NOW!!”

The most experienced man on the crew, besides the captain, was Bernie Breeck of Madison, Indiana, who always handled matters aboard the rig in a calm, professional manner born out of many years on the river. So when the skipper began shouting out of the open pilothouse window, and everyone but Bernie started running around the deck like scared cats, I followed alongside Mr. Breeck to the closest hatch near where BIG JOHN kissed the sunken steel beneath the turbulent water. Opening the lid, I was amazed to see waterfalls of frigid river water cascading from sprained seams falling into the bottom of the deep, riveted hull.

“Help me find some pumps!” Bernie advised. “Lots of ’em!”

Soon we had four three-inch-hosed gasoline-driven pumps expelling over 200 gallons per minute, per pump, from the rapidly-filling cavernous hull. After another pump was found and put online, the water level began slowly ebbing until one of the engine’s sputtered and was about to run out of fuel and stop. Snatching a five gallon can of gasoline, Bernie started pouring the highly volatile fuel into the pump’s tank located very close to an arcing spark plug. How we weren’t all blow to the shores of the Styx, I still don’t know. But, the old pro filled tank after tank and kept the pumps going until the water level was low enough that another deckhand and I descended into the hulk and drove oakum and shingles into the open seams to stem the incoming tide.

By nearly midnight, Captain Beatty finally declared the emergency repairs complete, and BIG JOHN was spared an embarrassing watery grave next to the sinkers it intended to rescue when it became a victim, instead. With the crane, hopper barge, and the CLARE safely in place and the cascading flooding reduced to a tiny weep, the Captain excused his exhausted crew for the night. Not a man rowed the yawl ashore to find a bar for one last, late-night round before the real work began before the coming dawn. Instead, the crew crawled into their racks and slept like dead men until the smell of frying bacon and the shouts of the “Old Man” aroused them to another day on the salvage fleet.

Captain Beatty hired a wetsuit diver, versed in the ways of marine recovery, to descend into the cold, murky depths to attach shackles to the ends of the hulls of the sunken barges to connect them to the stout hook of the steam crane. Once rigged, BIG JOHN could lift either end of the sinker until it surfaced and made safely secure to the hopper we brought along. That way, one end of the barge was above water and as soon as its forward rake compartment was pumped out, that section, once more, had buoyancy.

The Ohio River was so bitterly frigid that a large cooler, filled with warm water brought from the kitchen to the where the diver sat on the edge of the crane barge, stood patiently waiting until the diver pulled the neck of his rubber suit open. Then, two men lifted the cooler and poured the tepid liquid into his suit to keep him as warm as possible once he plopped into the water and descended below to do his work.

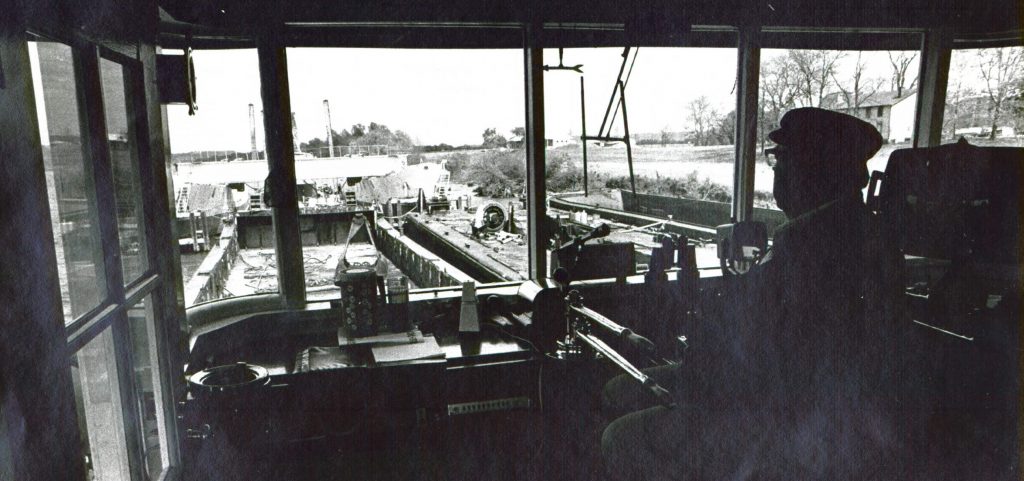

After several descents, the diver reported that all the hardware was in place on the deck of the first sunken coal boat. Satisfied with the conditions below, Captain John, who was at the levers and pedals of the vintage steam crane, began lifting. Greasy, black smoke spewed from the stack on the roof atop the boiler as BIG JOHN’s boom tilted towards its load while I was standing on the forward end of the crane deck, closest to the sinker, manning a capstan line that also pulled on the wreck.

But, instead of lifting the submerged barge from the water, the floating hull of the crane sank deeper and deeper into the river. Within minutes, the deck beneath me was awash. Higher and higher the freezing water rose until I was holding onto the capstan line with the Ohio River swirling around my waist.

Unexpectedly, without warning, the downstream end of the sunken barge abruptly shot up from the bottom of the river and arose from its watery grave like a breaching whale!

While I was standing face to face with the sodden, gray ghost arisen from the depths as the crane barge resumed its proper level in the water, the Captain shouted:

“Hold on to everything! Keep that capstan line tight!”

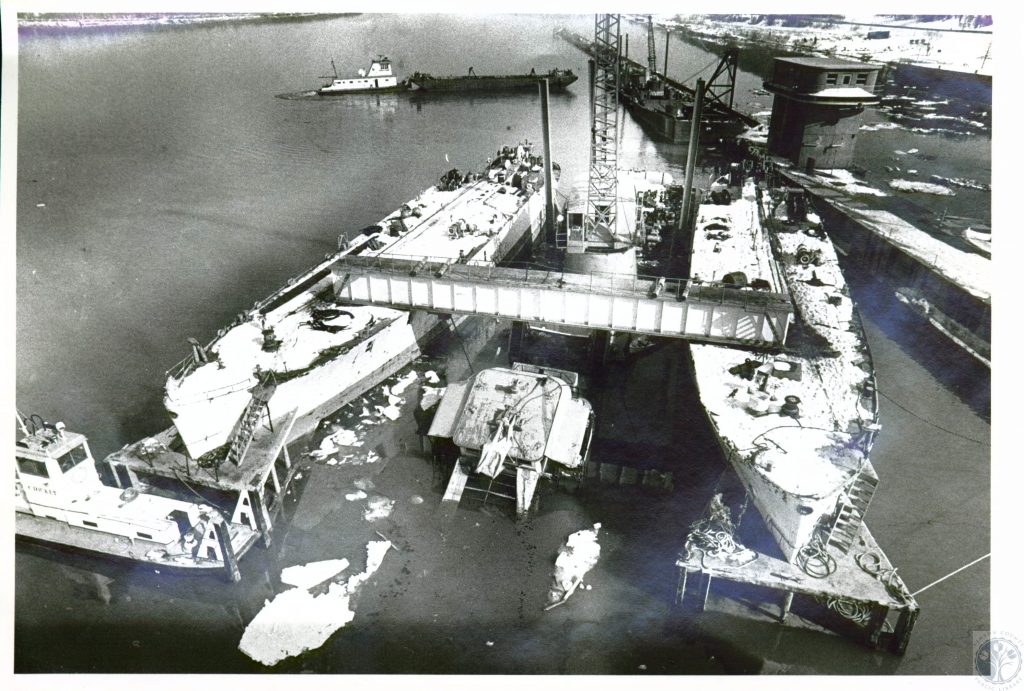

By then, no lines or cables secured our part of the salvage fleet to the sturdy ice piers. Only the minesweepers and other unneeded floating gear were attached. The only connection holding us in front of Gallipolis city was our attachment with the sunken barge. But upon its immediate rapture, the object to which we depended on for anchorage, suddenly became partially buoyant and unable to secure our fleet in place. The angry current ripped the entire conglomeration of two cranes, a floating barge, or two, and thankfully, the towboat CLARE E. BEATTY away from the wreck site and sent everything sailing down the Ohio River toward Gallipolis Lock & Dam, not that far away, heading downstream in such dire waters.

Captain Beatty, still at the controls of BIG JOHN, tore from the steam crane and raced toward the CLARE where both engines of the towboat were idling under the watchful eye of the long-time Chief Engineer of the former SEMET who was aboard for the trip to acquaint Captain John with the mechanicals of his new boat. By the time Cap was at the wheelhouse controls, the entire fleet was merrily cartwheeling down the swollen Ohio – end-around-end.

When Cap eventually regained control of the situation, the tow was more than a mile downstream from where it broke loose. Entirely unable for shove upstream against the might of the flood with the half-submerged barge hanging on, the captain shoved into the West Virginia shore where the small fleet remained there until the barge eventually refloated. Both of the crane flats were equipped with long, massive, pole-like appendages called “spuds” that could be lowered to hold onto the bottom of the river bed. The spuds securely the fleet into place once they were “set.” At the end of each day, while we operated at the temporary site below town, the spuds held the working equipment there while the CLARE was taken back upstream to where the minesweepers lay moored below the piers. The old ships required constant watching as they were “leakers,” and needed pumping each morning before breakfast.

Before we left to return to the city front for the night, lights were required on both fleets. Captain Beatty still preferred the use of kerosene lamps over battery-powered light. The task of keeping the oil-fueled lamps cleaned and refueled was the duty of Captain John’s nearly ninety-some-year-old father, Captain Clem Beatty, a renowned riverman in his own right. The elder Captain Beatty was usually called, “Cappy Beatty,” or just plain, “Cappy.” At dusk, Bernie and I collected the cleaned and refueled lamps and gathered them into the wooden Weaver Skiff. While Bernie rowed, I sat in the bow and secured each kerosene lantern in place on the vessels and protruding wrecks as required by the regulations of the U. S. Coast Guard. Once we set the lamps in place, we eagerly returned to the CLARE for dinner.

As Bernie and I left the galley after eating our share of the evening meal, he noticed that the lamps were dark instead of burning brightly. Again, we climbed into the Weaver Skiff, and when the first lamp was alongside, I raised the clear glass lens, relight the flame, and closed the lens. The bright-white light burned merrily for several seconds while we watched, but then it blazed into an intense flare for an instant before extinguishing itself with a loud, “POOF!” Again, I relit the lamp, but the process repeated itself.

“Check and see if it’s got any oil,” Bernie suggested.

After unscrewing the cap on the fuel tank, I put my finger over the hole and shook the lantern to soak my fingertip with the contents and brought my wet finger to my nose, sniffed, and turned toward my partner and said in a puzzled tone:

“It’s Gas! The lantern is full of gasoline!”

All the lamps proved to have the same disorder, and they were collected, refueled, and reset. Sometime after I left Cap’n Beatty’s employment, a mutual acquaintance informed me that my former captain often repeated:

“That Don Sanders… he doesn’t even know how to light a kerosene lantern!’

On one of the nights after the CLARE returned to the city front, the cook and his deckhand buddy rowed the yawl ashore. After they returned to the CLARE once the last saloon in town closed, the racket would have raised Lazarus. The boys roused the Captain, and once they had his undivided attention, they unloaded on some issues that had been festering between them about the conditions of their employment since they came on the CLARE soon after Cap’n Beatty bought the boat. Whatever transpired among the three was enough, that by morning, no fried eggs and bacon or sausage and gravy were waiting for the hungry crew in the galley at breakfast time. Captain John, though, had a large pot of oatmeal steaming on the galley range and a pot of strong steamboat coffee brewing. Cap promised to hire a cook as soon as he could find one in town.

Just before noon, a skinny bedraggled lad who looked like he could stand a good meal, himself, was introduced as the “new cook.” So at lunch, instead of the hearty grub, the former cook always served, a boiling pot of canned navy beans and white bread were the crew’s fare. By dinner, the menu repeated itself. As each of us looked glumly at our plates, Captain John wore a broad smile on his face as he cheerfully masticated a mouthful of cheap, canned beans. For all us seated around the table to understand that this meal was a precursor of what was to be, he loudly proclaimed:

“Best cook I ever had… Yes, Sir… This boy’s the best cook I ever had!”

Captain Don Sanders is a river man. He has been a riverboat captain with the Delta Queen Steamboat Company and with Rising Star Casino. He learned to fly an airplane before he learned to drive a “machine” and became a captain in the USAF. He is an adventurer, a historian, and a storyteller. Now, he is a columnist for the NKyTribune and will share his stories of growing up in Covington and his stories of the river. Hang on for the ride — the river never looked so good.

Captain Don Sanders is a river man. He has been a riverboat captain with the Delta Queen Steamboat Company and with Rising Star Casino. He learned to fly an airplane before he learned to drive a “machine” and became a captain in the USAF. He is an adventurer, a historian, and a storyteller. Now, he is a columnist for the NKyTribune and will share his stories of growing up in Covington and his stories of the river. Hang on for the ride — the river never looked so good.

Cap’n Beatty was rough and challenging, but under his hard exterior, beat the heart of an honest, fair-and-square gentleman worthy of the highest praise. Mrs. Clare Beatty was the “brains of the outfit,” as she was often called. Cap’n John’s most demeaning flaw was failing to treat his crew respectably — a trait ingrained in him growing up. “If I want a deckhand,” he often said he was taught as a youngster, “I’ll go out on the riverbank, find me a hunk of driftwood, and whittle one.” I would have stayed with Captain Beatty if he had treated me differently. Otherwise, it’s a brag saying I worked for him.

An engaging story continues to unfold on multiple fronts. Murphy’s Law surely has a subsidiary dedicated for riverboating!

I have Sailed with the Engine Equivalent of Capt Beatty, but in most cases if you did and Knew Your Job, things went fairly well. OTOH It takes a Tough Guy like Capt Beatty to DO the tough jobs like Capt. Don. describes.