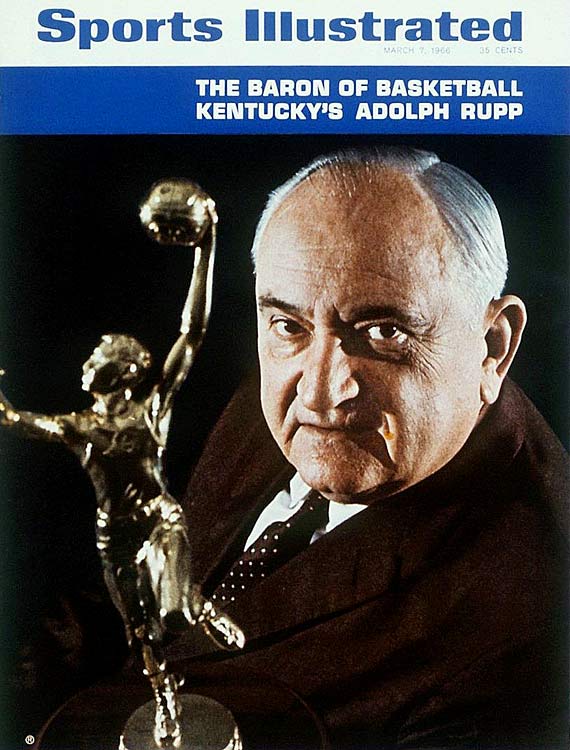

I’ve been dreading the arrival of 2016 because it’s the 50th anniversary of Texas Western’s historic 72-65 victory over Kentucky in the NCAA championship game. The Miners were the first team with five black starters to win the title, and the all-white Wildcats and their coach, the authoritarian Adolph Rupp, were the perfect foils in a game that writer David Israel later called “the Brown v. Board of Education” of college basketball.

Much as I appreciate Israel’s clever turn of phrase, I’ve always thought it a bit hyperbolic. Teams with two, three and four black starters already had won NCAA tittles. An all-black starting five was the next logical progression, and nobody at the time made a big deal of the racial angle, including writer Frank Deford in his Sports Illustrated cover story.

But in 1991, another of my former SI colleagues, Curry Kirkpatrick, observed the 25th anniversary of the game by turning it into a morality tale in which Rupp was cast as the Bull Connor of college hoops. Connor, of course, was the racist Birmingham police chief who ordered the use of clubs and fire hoses against black protestors during the civil rights protests of the 1960s.

I’ve never claimed to know what was in Rupp’s heart when it came to race. But I have collected a set of facts that prove he wasn’t nearly the vile racist that Kirkpatrick portrayed in his SI piece. Yet I’ve watched the Kirkpatrick version adopted as gospel by revisionist historians in the media and Hollywood. They have reduced a very complicated, nuanced story to a simple matter of black and white, literally, and that’s just not right.

I’ve laid out my facts in numerous columns over the years. I know what I’m talking about because, well, I was there. As a senior at Transylvania University in 1966, I already was assistant sports editor of The Lexington Herald. I knew the UK players as friends, which may be why my version of the story has been dismissed out of hand by those determined to believe there’s only one side to the story.

What they don’t know is that I would be the first to say so if I thought the facts proved conclusively that Rupp was a racist. I was the first white reporter to cover games at all-black Dunbar High in Lexington. I was one of the few to seek out Perry Wallace, the first black player in the Southeastern Conference, when he was a freshman at Vanderbilt. I’ve always stood up for black coaches and players.

Over the years, I’ve been interviewed by various networks that told me they wanted to do a documentary about the 1966 title game. I’ve always done those interviews, only to be disheartened to see that my arguments regarding Rupp never made the final cut. They weren’t interested in anything that deviated from the standard story line.

I figured I might get similar requests this year, and, sure enough, here came an e-mail on Dec. 16 from Adam Goldberg, who told me he ran a production company called South District Films that was producing a hour-long show for CBS about the 50th anniversary of the Kentucky-Texas Western game.

“In honor of the anniversary,” said Goldberg, “UTEP is hosting a panel discussion on Feb. 5 in El Paso…I know you have an extensive knowledge on this subject, so we would very much like to see if you might be able to attend and be a part of the event. We think your participation is key to both a successful panel discussion and the subsequent CBS show. UTEP is providing transportation and accommodations for the event…”

I responded immediately.

“I would most definitely be interested provided that all parties understand that my views of the story are markedly different from those as adopted as fact by Hollywood and revisionist historians.”

This led to a subsequent phone conversation with Goldberg. He had read some of my columns about the game and he assured me that, as a documentarian, he wanted my voice involved. But just to make sure everyone was on the same page, he said he wanted to mention my position to UTEP and CBS.

On Jan. 4, I got his response.

“Hey, Billy,” he said, “I wanted to get back to you and thank you for wanting to be part of the show. Unfortunately, the network feels this isn’t the best fit. Thanks again for offering to help.”

I’m fine with that. I had no desire to go to El Paso and participate in yet another dog-and-pony show. But I can’t help but wonder why CBS decided that I’m not a good fit instead of being what the producer called “a key” to the program. If CBS has found somebody more qualified to give the Kentucky side of the story, that’s fine. But I fear the network is just going to perpetuate the myths and misperceptions that have grown around the game.

A few quick facts about Rupp:

• He had a black player on his team when he was a high school coach in Freeport, Ill., before coming to UK in 1930.

• He was assistant coach on the 1948 U.S. Olympic team that won the gold medal in London with the help of Don Barksdale, a black player from UCLA. Barksdale has said some nice things about Rupp.

• As early as 1951, when an African-American named Solly Walker led St. John’s into Lexington, Rupp was scheduling non-conference games against teams with blacks. Nobody else in the SEC or Atlantic Coast Conference was doing that.

• In 1959, he offered Felix Thruston of Owensboro, Ky., High the opportunity to become UK’s first black player. Thruston turned him down because of the violence that was building in the Deep South. His brother Jerry, also a standout basketball player, told me his family had a good experience with Rupp.

• In 1964, when both the SEC and ACC were still lily-white, Rupp offered a scholarship to Wes Unseld of Louisville’s Seneca High. But Unseld didn’t have the temperament of be a pioneer in the Deep South, where blacks were being routinely kidnapped and hung.

• In 1965, black star Butch Beard of Breckenridge County told Rupp he was coming to UK. But Beard changed his mind and joined Unseld at Louisville when a stranger came to his family’s home and said he would be killed if he went to UK.

When it looked as if Beard were going to UK, Sports Illustrated sent Deford to Lexington, and he wrote a story that praised Rupp for leading the integration of southern basketball.

“For 12 decades, the 12 schools in the SEC have had a gentleman’s agreement not to field Negro athletes,” Deford wrote. “Kentucky’s pursuit of Beard means that the SEC has a new gentleman’s agreement to forget the old one, and thus the last major conference color barrier has quietly fallen.”

Rupp, who earned a master’s degree from Columbia, was no dummy. He saw how blacks were changing the game and he valued winning above all. But so what if his motives were more pragmatic than pure? He was, in fact, the first coach in either the SEC or ACC to recruit blacks.

This is the point of view I wanted to bring to the CBS program. In the interest of fairness, which has taken a horrible beating in this case, I hope they find somebody else who was around at the time, who actually knew Rupp, to give the rest of the story.

But excuse me for saying that I’m not holding my breath.

Billy Reed is a member of the U.S. Basketball Writers Hall of Fame, the Kentucky Journalism Hall of Fame, the Kentucky Athletic Hall of Fame and the Transylvania University Hall of Fame. He has been named Kentucky Sports Writer of the Year eight times and has won the Eclipse Award twice. Reed has written about a multitude of sports events for over four decades, but he is perhaps one of media’s most knowledgeable writers on the Kentucky Derby.