By Steve Flairty

NKyTribune contributor

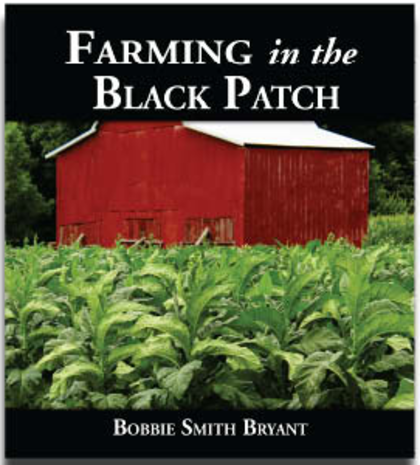

I reflected on my youth around the family tobacco farm recently while reading Farming in the Black Patch (Acclaim Press, 2015), by author Bobbie Smith Bryant. The book is a well-done account of Bryant’s family (Smiths and a few others) raising dark-fired tobacco in the westernmost part of Kentucky, called the “Black Patch” area. It is a follow-up to the Michael Breeding produced PBS documentary of the same name, of which Bryant served as the associate producer.

There’s an assortment of ways to respond to the experience of tobacco culture resembling what Bryant and I encountered living in different parts of the state. I wrote about my thoughts in a previous Kentucky by Heart column, sharing memories of setting the crop, taking care of it as the plants grew to maturity, harvesting, and stripping the tobacco in my community of Claryville, in Campbell County.

My brother, Mike, a born farmer, enjoyed much of the seasonal process, especially when it involved tractor driving. But except for a few things that resembled fun, I didn’t much care about the hours of hard work and focus involved.

That said, I now see some valuable life lessons from being a part of the tobacco culture, most importantly the work ethic developed. And though I realize the health dangers of tobacco use, the burley culture of my youth works well for me as an adult. The overall message of Bryant’s book helps to articulate ways that are so.

In the beautifully illustrated and easy-to-read book, Bryant highlights her western Kentucky farm roots to bring alive a summative picture about the raising of dark-leaf tobacco. She focuses on looking carefully at the crop working processes of several families who know their craft well, and who obviously care passionately.

There are differences in raising the lighter leafed burley tobacco found east of there (the crop I worked in). Bryant’s stories nevertheless connect to my past in many ways — and powerfully so.

I am amazed at the technological advances in tobacco farming that Bryant shares in text and in pictures. I enjoyed the burning of tobacco beds as a kid. We burned brush from downed trees near our creek to kill off weed seed, then sewed packets of tiny tobacco seeds on long, narrow soil “beds.”

Today, said Bryant, “plant beds and tobacco plants are 99 percent commercially grown and purchased by the local farms.” The tobacco setter implements are far more elaborate, and in the “stripping” process (taking the cured leaves off the stalk), the leaves today are placed loosely into a container box, and are more often mixed in grades. As a kid, I tied many a “hand” of tobacco and there were many grades for which to separate by color. That hand was then moved to a tobacco press that my father and built, which left the leaves taking less room for storage.

A major difference in the burley of my youth in Northern Kentucky and Bryant’s dark tobacco are in the curing methods. We simply hung the stalks on wooden sticks in barn rails and waited for nature to gradually turn the leaves a somewhat golden brown color. In the dark-fired curing process of Western Kentucky, an actual smoking event happens over an extended time inside the barn, using wooden boards and sawdust in a slow burn. As Bryant demonstrates, it bears keeping a watchful eye, both for safety and optimal leaf coloring.

In describing the highly nuanced art of controlling the environment of the barn and doing the “burn” effectively, farmer Billy Dale Smith said: “All barns have a personality, just like each one of us do. And after you deal with them, you learn their personalities.” To do so takes close, intentional focus.

The book has an informative section on the history of tobacco dating back to 6000 BC, when experts think the plant was growing in the Americas. Most fascinating, to me, is reading about the infamous Black Patch War, dealing with the monopolistic American Tobacco Company and the resulting strike among the tobacco growers, who had formed a cooperative. Violence ensued when some farmers broke the strike and sold their crops to the company.

Bryant shares an extensive interview with author and Kentucky Supreme Court Judge Bill Cunningham about the conflict. The story, through Cunningham, is riveting—and a sad chapter in the state’s history.

According to the author, Black Patch tobacco farmers rely heavily on the teamwork afforded by their family efforts. Statewide, the number of farms are dwindling, but the average size of acreage has increased tremendously. Consequently, those farms are relying on foreign workers having H-2A visas to work the crops. The relationship has been good, stated Billy Dale Smith. “Most of my H-2A workers have been helping me for a really long time. I’ve got four who have been helping me for ten years or longer.”

One migrant worker on the Smith farm talked about the good work atmosphere he enjoys: “I’ve done a few small things that didn’t turn out right at work, and they tell me things like what I have to do, what I don’t have to do, but not in a chastising way, just a point of view to do things better.”

There’s a plethora of tobacco-raising terms that Bryant defines in context or in a helpful glossary. Examples are: cooperatives, the Fair and Equitable Tobacco reform Act, hogsheads, hanging tobacco, price support, side dressing, and many others. The book is a wonderful primer for those who have little background on the subject, or a nice review for those who have been away from it a while, like me.

Farming in the Black Patch portrays well a way of life in Kentucky that may be losing some steam as tobacco growing diminishes because of health concerns, yet is still making its mark in positive ways. Family, hard work, and a sense of teamwork will always be welcome somewhere.

Bobbie Bryant currently is a community development advisor for the Kentucky League of Cities, has written two other books, and is a featured speaker of the Kentucky Humanities Council. She lives in Louisville with her husband, Bill Bryant.

Steve Flairty is a teacher, public speaker and an author of six books: a biography of Kentucky Afield host Tim Farmer and five in the Kentucky’s Everyday Heroes series, including a kids’ version. Steve’s “Kentucky’s Everyday Heroes #4,” was released in 2015. Steve is a senior correspondent for Kentucky Monthly, a weekly NKyTribune columnist and a member of the Kentucky Humanities Council Speakers Bureau. Contact him at sflairty2001@yahoo.com or visit his Facebook page, “Kentucky in Common: Word Sketches in Tribute.” (Steve’s photo by Connie McDonald)