Editor’s Note: First in a four-part series on Kentucky’s Parole Board.

By R.G. Dunlop

Special to NKyTribune

Lance Conn was just 20 years old when he helped rob and murder an elderly Frankfort woman in July 1994.

The 77-year-old victim was found five days later stuffed in the trunk of her car at Blue Grass Airport in Lexington. She had been strangled. Conn and his two accomplices allegedly had conspired to steal silver, coins, and jewelry from her home.

Crystal Ware, one of the co-defendants, was convicted of robbery and criminal facilitation to commit murder and sentenced to 19 years in prison. She was granted parole in 2002 and released from parole seven years later.

Stephen Marshall, who according to court records was the primary perpetrator, was convicted of murder and robbery and sentenced to life without parole for 25 years. He will be eligible for release on July 1, 2029.

But Lance Conn likely will die in prison, despite a 2014 Kentucky Parole Board decision that he would never be released from custody based partly on the false premise that Conn had a prior felony conviction.

Even after the board granted Conn’s request to eliminate that incorrect information from his record, it refused to reconsider its decision that he would never be paroled. And when Conn asked the board a second time to take a fresh look at his case, its answer was the same: No.

Documents also show that while board member Caroline Mudd decided that the reference to “prior felonies will be removed, as there were none,” there was no admission of error by the board.

The documents further show that Mudd concluded that, notwithstanding the erroneous information, there was “no significant new evidence” to justify reconsideration of Conn’s case. Mudd, who is no longer on the parole board, refused to be interviewed by this reporter.

The state Justice and Public Safety Cabinet, of which the parole board is a part, did not respond to questions about Conn’s case, including why he was deemed by the board to be forever ineligible for parole, while Marshall — the principal defendant — could receive parole consideration in less than four years.

Now 51 years old, Conn remains locked up at the Eastern Kentucky Correctional Complex in Morgan County, serving his 30th year behind bars with little hope of ever regaining his freedom. Efforts to interview Conn were unsuccessful.

‘Board wields significant power’

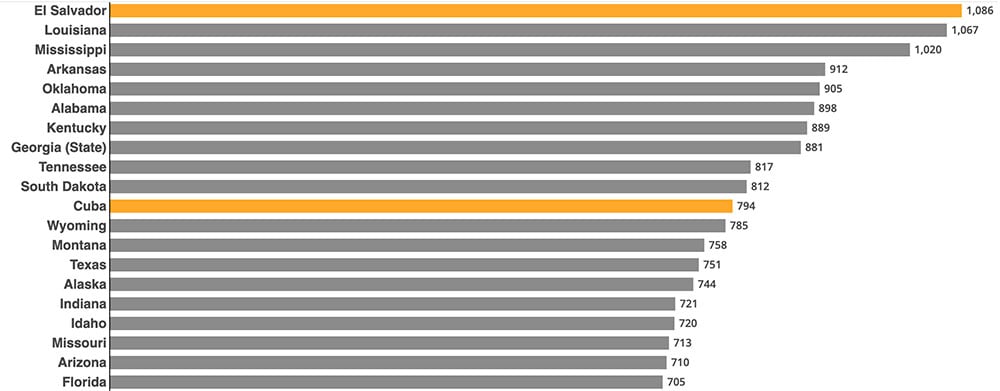

Kentucky has the sixth-highest incarceration rate of any state in the country, and one of the highest rates in the world. And since most Kentucky inmates eventually are eligible for release after sentencing, it’s not surprising that the parole board has a lot to do.

In 2023, the board handled a total of 15,720 cases, slightly fewer than the previous year. And in February 2024 alone, the board’s caseload totaled 1,003 hearings and reviews.

The statistics don’t specify the number of cases involving life without parole. But according to information provided by the state Department of Corrections in response to an open-records request, at least 84 inmates have been given that sentence since January 2014.

The parole board’s questionable handling of Conn’s case is hardly the only issue of interest and concern involving the board.

When the Kentucky Supreme Court ruled unanimously in April 2024 that the board has the legal right to impose sentences of life without parole, Justice Michelle Keller issued a detailed, critical 14-page opinion questioning the propriety of imposing serve-outs (requiring completed sentences) and other issues related to the parole board.

“The board wields significant power over the life and future of Kentucky inmates,” Keller wrote. “It is clear that the board’s internal policies lack any compulsory review processes to check against the board’s unfettered discretion to grant serve-outs of life sentences.

“Given the gravity of the interests at stake, I must express my concern that the parole process itself, along with the lack of checks on the power of the board, could result in said power being wielded in a manner inconsistent with our constitution.”

In a 2016 sworn statement, then-parole board Chair Lelia VanHoose said each of the nine board members may have spent an average of 25 minutes or less on the roughly 85 parole-related decisions they made each week.

As a result of that brevity, Keller wrote in her opinion, “some information is inevitably going to be overlooked. This is especially concerning in any decision to serve out a life sentence, given the incredibly high interests at stake in those decisions.

“Board members have access to an abundance of information about an inmate, but are provided no guidance on how to weigh that information in making their parole decisions. Even if board members wanted to review all of the information provided to them and carefully weigh it, they likely would not have enough time to do so, given their burdensome workload.”

Franklin Circuit Judge Phillip Shepherd raised a similar concern in an October 2020 ruling.

“The board’s practices in processing the enormous volume of parole reviews raise questions in terms of whether the board’s policies and procedures are governed by objective criteria, and whether they provide for fair consideration of the issues,” Shepherd wrote.

While state law requires the Department of Corrections to provide certain information to the parole board, the law “does not place a similar duty on the board members to consider that information,” according to Keller’s opinion. “Nor does it instruct the board on the weight to be given each piece of information.”

The law and the parole board’s own regulations “provide no guidance as to when a serve-out of a life sentence is appropriate or what information the board should consider in making that life-altering decision,” Keller wrote.

Those regulations require the board to apply one or more of 16 factors to an inmate’s case before recommending or denying parole, including the inmate’s current offense, prior record, history of substance abuse, and past education and employment.

But Keller’s opinion concluded that because only one of the 16 factors must actually be considered by the board, an inmate’s “life could forever be altered in a nearly irrevocable way based solely on, for example, his lack of employment history, or lack of education, or drug use which could date back decades.”

Keller added: “He could even be denied any further opportunity at parole based solely on the seriousness of his offense, which, I must emphasize, was already taken into consideration when the judicial branch chose to sentence him to life in prison while still allowing the possibility of parole.”

Justice Keller said in an interview with this reporter that while she doesn’t think the state should ban sentences of life without parole, “the ball is back in the legislative arena. Are the interests of the Commonwealth being met by this system the way it is?”

Part of the answer, she said, might lie in a larger board “where individual parole board members are not so completely overworked. It’s always all about money. I guess you’d need more funding.”

Keller is by no means the only critic of the state’s parole process. Attorneys for Conn and other inmates who unsuccessfully contested sentences of life without parole have raised many of the same concerns. Betsy Matthews, an associate professor in the School of Justice Studies at Eastern Kentucky University, also reviewed Keller’s opinion at this reporter’s request, said, “I agree with all of Judge Keller’s comments.”

In addition, critical assessments of Kentucky’s parole process were echoed in a 2019 study by the nonprofit Prison Policy Initiative, which reviewed parole systems in all 50 states and gave Kentucky’s a grade of “F”.

Kentucky had plenty of company. According to PPI’s analysis, Wyoming received the highest grade, a B-. Five states got Cs, eight received Ds, and the rest got either an F or an F-. Kentucky received 59 points out of a possible 100 in the survey. Wyoming got 83.

Among the areas where Kentucky’s process got marked down: The parole board allows input from prosecutors and victims, which PPI argues should be prohibited.

Prosecutors’ “voices belong in the courtroom when the original offense is litigated,” the PPI study contended. And while the parole process “should be about judging transformation, survivors (victims) have little evidence as to whether an individual has changed, having not seen them for years.”

The state parole board also lost points in the PPI study for not having a policy of “presumptive parole,” which essentially guarantees parole for inmates who meet certain criteria.

Wandra Bertram of PPI said after reviewing Keller’s opinion at this reporter’s request that she basically agreed with “all of the points Judge Keller makes about the parole board’s decision-making process and the harsh, counterproductive nature of life without parole.”

In particular, Bertram noted Keller’s concern that an inmate can be denied parole solely due to the seriousness of his offense.

“The Board is giving itself a blank check to deny release based on something the applicant (inmate) has absolutely no control over,” Bertram said.

The state Justice and Public Safety Cabinet, of which the parole board is a part, denied this reporter’s request to interview parole board Chair Ladeidra Jones and board Director Angela Tolley pertaining to issues raised by Keller’s opinion and other sources about parole-related matters. Instead, the cabinet suggested that written questions be submitted.

But the cabinet’s response addressed none of the more than 40 questions provided, including those pertaining to the parole board’s problematic handling of Lance Conn’s case. Instead, the cabinet provided a one-paragraph email reply stating in part that the parole board “adheres to statutes, regulations, and policies in issuing parole decisions.”

Attempts to interview seven current or former parole board members in addition to Jones were unsuccessful. All either declined to be interviewed or else did not respond to numerous messages seeking comment.

Eight of the nine current parole board members were appointed to their four-year terms by Gov. Andy Beshear. The ninth member, Jones, a former probation and parole officer, was named to the board in December 2019 by then-Gov. Matt Bevin, and was designated by Beshear as the board chair in July 2021.

Next: Life-sentences pose financial challenges for prisons facing aging inmate population