By Berry Craig

NKyTribune columnist

Generations of Kentucky politicians knew that the true path to voters’ hearts ran through their stomachs. Servants of the people plied the body politic with burgoo.

“A ‘burgoo’ is a cross between a soup and a stew, and into the big iron cooking kettles go, as we sometimes say in Kentucky, a ‘numerosity’ of things – meat, chicken, vegetables, and lots of seasonings,” recalled Vice President Alben Barkley of Paducah in That Reminds Me, his 1954 memoirs.

The concoction became so synonymous with politics in Kentucky that a political rally which featured the stew was called a “burgoo.” Barkley described himself as a frequent partaker when he “toured the political hustings in certain parts of the Blue Grass State.”

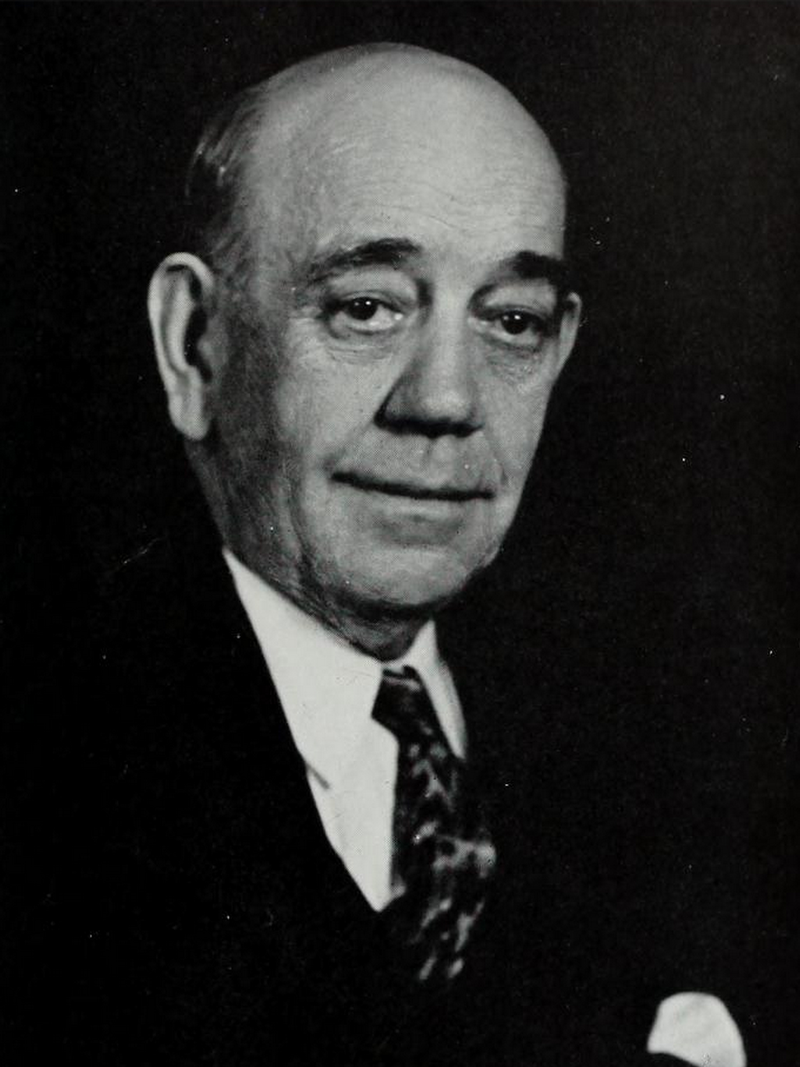

There were big burgoos everywhere. One of the largest was at Mayfield on Oct. 17, 1931. The occasion was a visit by Judge Ruby Laffoon of Madisonville, the Democratic gubernatorial hopeful that grim Depression year.

More than eight hundred gallons of burgoo were brewed in 52 iron kettles over smoky blazes that made the Mayfield Messenger mindful of “Chicago after a certain historic cow had kicked over a lantern and set fire to two thousand acres of property.”

Dr. Bow Reynolds was the “master of affairs and chief cook,” according to the paper. Twenty volunteers helped, tending kettle fires and preparing the ingredients for the burgoo blowout: a ton-and-a-half of beef, a half-ton of pork, forty bushels of potatoes, forty bushels of onions, 480 cans of tomatoes, forty bushels of carrots, 1,200 roasting ears [of corn], forty gallons of peas, a bushel of red peppers and a gallon of garlic.

Approximately 7,000 people, evidently from the 13-county First Congressional District showed up to hear Laffoon and Albert B. “Happy” Chandler, the Democrat running for lieutenant governor, give speeches and sample the free burgoo at the old Mayfield High School football field, now Mayfield Middle School’s back campus.

Reynolds and his aides began brewing the burgoo the Thursday night before the Saturday rally. Burgoo central was the Jackson Purchase stockyards west of town.

“Down through the middle of a large covered stock pen is a long alley extending from one end to the other,” a Messenger writer described the scene. “On either side are stalls, formerly occupied by livestock but now inhabited by peelers of potatoes, carrots, onions and various other vegetables. In the alley is a row of forty old-fashioned iron kettles. Some are as large as a barrel in circumference, and others are larger.”

The paper’s scribe found the “pots boiling…and they had just sent for a dozen more.” The Messenger suggested that “no one person probably will ever know how many different things are in a batch of burgoo.” But the paper assured its readers that the burgoo contained nothing metallic because “all cans have been removed from around the tomatoes before they were dunked.” The Messenger described the stew as “a six-course dinner all boiled in one…With proper seasoning burgoo can’t be anything but good and nutritious.”

The burgoo was served in pasteboard cartons with slaw and bread for sides. It took three hours to feed the multitude, the Messenger reported.

“There was plenty to eat,” the paper also said. “Scores of gallons” went unconsumed because Reynolds and his helpers made enough burgoo for 10,000. Reportedly, the leftover burgoo was given to a local charity for feeding the hungry.

While Reynolds’ recipe called for beef and pork, earlier burgooists used wild game.

Berry Craig of Mayfield is a professor emeritus of history from West Kentucky Community and Technical College in Paducah and the author of six books on Kentucky history, including True Tales of Old-Time Kentucky Politics: Bombast, Bourbon and Burgoo, Kentucky Confederates: Secession, Civil War, and the Jackson Purchase, and, with Dieter Ullrich, Unconditional Unionist: The Hazardous Life of Lucian Anderson, Kentucky Congressman. Reach him at bcraig8960@gmail.com