By Mike Rutledge

NKyTribune reporter

Two and a half years after Irvin “Butch” Callery left the office of Covington’s mayor and moved to the leafy, suburban city of Villa Hills, news reporters had to ask him, if only in jest: Was he going to become involved in his new city’s politics?

No, Callery answered with a laugh. He had no interest in doing that.

That seemed a very wise decision. After all, he not only survived 29 years of the sometimes jarring politics in Northern Kentucky’s largest city, but also seemed to thrive on leading during his 21 years as a city commissioner and eight years after that as mayor. But he ultimately had been beaten down in a rugged 2008 mayoral campaign.

Unlike earlier campaigns, Callery in 2008 abandoned his proven method of extensive door-to-door campaigning. And when challenger Denny Bowman, himself a former Covington mayor, bombarded voters with arguments that Callery should be considered the lesser candidate, the incumbent barely fought back. Instead, Callery had remained stoic and civil. He lost 58-42 percent.

Why on earth would anyone – even Callery, or especially Callery – want to get involved in the even more volatile politics of Villa Hills, which at the time were regularly erupting with angry city arguments that were creating embarrassing headlines?

Only two days after Butch and Joyce Callery moved into their Villa Hills home from Covington’s Latonia neighborhood in August, 2011, he says, a lady from down the street asked him, “You’re the Butch Callery who was mayor of Covington?”

“I wanted to ask you,” she continued, “if you’d be interested in running for mayor in the next election.”

“No,” he told her, again with a laugh. “I’d have no interest at all’.”

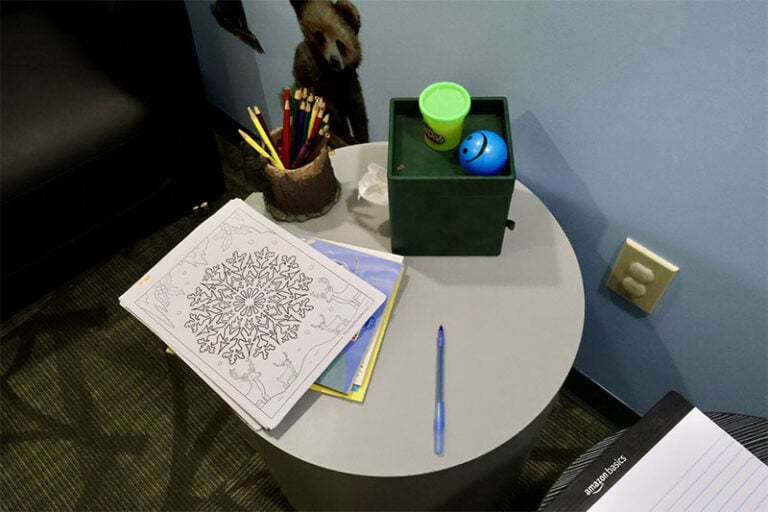

And yet, here he was just last Thursday, in January 2015, sitting in the nearly empty Villa Hills mayor’s office, about half the size of the Covington mayor’s suite he left six years and a few days earlier. And Joyce, who had wanted to be spirited away from Covington’s politics to a more peaceful place, had given her blessing to this political encore.

In the campaign that ended his Covington political career, “I didn’t do it like I used to,” Callery recalled during an interview last week. “I was getting burned out. You can imagine, after 29 years….”

Some of Bowman’s attacks during the Covington mayoral race were “completely untrue,” Callery said. “Like I fired all these people.” In reality, as Covington’s mayor, he says: “I couldn’t fire anybody.”

Villa Hills, a city of 7,300 residents, has seen more than its share of political controversy in recent years. Mayors have battled with the police department. The council that held office in 2011-12 attempted to impeach Mayor Mike Martin, and vice versa. Several lawsuits have been filed and legal fees have climbed.

Callery became more interested in running for mayor after serving on the city’s Civil Service Board. The board was preparing to hear the case of a former assistant police chief involved in lawsuits against the mayor. It was setting up procedures and met with attorneys when Mayor Martin decided the council should hear the case, rather than the civil service board.

“And then, the civil service board said, ‘Hey, wait a minute, we were appointed to do this, a fourth-class city, so we should hear the case,’” Callery said. “So it went to court, but it’s never been resolved.”

“That’s what spurred me a little bit to run,” Callery said. “Because we would have done a very objective hearing on the case, and he took it over to the council. So that kind of upset me a little bit, and some of the council members. Because Gary Waugaman (who later would run for council and win a seat) was on with me, and we both ran. We wanted to hear the case.”

The civil service board later was abolished after state legislation allowed that. Meanwhile, Callery and the rest of the region kept seeing news about city controversies.

Then one day in about June, “about eight ladies in Villa Hills took Joyce to lunch,” he said, with a grin. They knew his wife of 47 years held a lot of sway. “And they said, ‘You’ve got to let your husband run for mayor.’”

After that lunch, “She said, ‘Do it,’ Callery said. “She was pretty supportive, because I was more relaxed” than in those final Covington days.

“I said, ‘Well, I think I’ll do it,’ Callery recalled. “I said, ‘When I do, I’m going to go all in.’ So I did. Did aggressive door-to-door, and I put out the things that I’d heard from people in my flyer, and it went over pretty well because I was concise and put a little bit of my record of my years in Covington.”

He worried some people would resent him running after only three years in the town. He heard some of that, but many said they respected his experience and decades of public service.

In November he won a four-way mayoral election, collecting 46 percent of the vote; compared to 26 percent by Ernie Brown; 20 percent by Martin; and almost 9 percent by Holly Menninger-Isenhour for the $2,400-per-year post.

Callery last week was clearing out old files and found his first Covington paycheck. In 1980, as a Covington city commissioner, he was paid $94 per week, after taxes, more than the $200-a-month he now will earn, “So I’m back to the future now,” he said. (He made about $26,000 a year as Covington’s mayor.)

On Dec. 16, swearing-in ceremonies were held for Callery and six members of the city council, most different from last year’s group. On the council that took office Jan. 1 were Gary Waugaman and Jennifer Vaden, both new to the council; Mary Koenig, the only member of this council who served the prior two years (she also was on council from 1990-2001); as well as Scott Ringo, Gregory W. Kilburn and George Bruns, who had served previously on the council but not the past two years. As mayor, Callery will vote on issues when the other six are tied.

Martin and Koenig both say they believe the prior regime left Villa Hills finances in strong condition.

“The last council, we did a lot of things to help the city financially, and I think the city is probably financially as strong as it’s ever been,” Koenig said. “We’ll just have to wait and see how it all shakes out, how everything works. But I think Mr. Callery is bringing a lot of experience, and he’ll be a good change.”

Moving forward

During his first week on the job, Callery, 73, said he undid executive orders by Martin.

“For example, the police chief wasn’t allowed to talk to the press,” Callery said. “Everything had to go through the mayor. So I thought, ‘that’s not a good thing.’ Because if (reporters) would call the chief on an incident, like a robbery or a murder, whatever, he’d have to check with the mayor,” Callery said. “So I thought, ‘Well, that’s not a way to handle things. When you hire a chief you should support him, and they’re not going to embarrass the city anyway, so this isn’t good.’”

“The public works director couldn’t talk to the city engineer, without permission,” Callery said. “So I’ve eliminated all of this so everybody can – you know, directors, not every employee – but that way, say the Enquirer called them about snow removal or something like that, the public works director can speak on it.”

Martin said the police chief recently has spoken to the media without restrictions. Martin said he had set a citywide policy that others in government could not comment after he saw a news release one employee was about to send out. It was filled with misspellings and grammatical errors that would have made the city look foolish, Martin said.

Martin said the public works spoke with the city’s contracted engineer many times, but was cautioned to be prudent with such talks because the city was being billed by the hour.

“Financial revenue we have has always been a struggle, because we’re such a residential community,” Martin said. “There’s little commercial base.”

Martin said while in office he examined every line item in the budget “to find ways to cut costs before we think about raising taxes, basically,” he said. “The mindset in the past had been ‘Just go buy stuff.’ My mindset is, ‘Before you buy stuff, is it a want or is it a need? And trying to change that mindset in some of the department heads’ and employees’ minds has been a little bit challenging. But that has slowly started to develop, where people are starting to ask the right questions before we just go out and spend money.”

The city has built surpluses, Martin said. When the current budget started July 1, “we started with a $150,000 surplus,” that it was hoped would go into reserves, before a police cruiser needed to be replaced, he said.

Martin, Callery and Koenig all praise current city employees, including Craig Bohman, himself a former Covington commissioner (2001-2003) who in 2013 became city clerk after years of vacancy in that position. Early last year Bohman became city administrator as well as the clerk.

Nowadays, “You don’t have employees submitting time sheets for unbelievable amounts of overtime,” Martin said. “Our police department budget is down $100,000 from a couple years ago, by restructuring and managing the employees.”

The city also cut taxes, in a fashion, Martin said. When the city’s traditional $40 vehicle-sticker program ended, with its revenues of $230,000 per year, it was replaced by 2 percent boost in the insurance-premium tax, which raised $175,000 yearly. Through other cost-cutting, the city increased spending on roads through increased payments from the general fund, he said.

“This year we have in the budget more money on roads in our general fund than we’ve ever had,” Martin said.

Eight full-time cops?

Callery has already increased the city’s number of full-time police officers to seven, with hopes of adding an eighth full-timer next budget year. Currently there are six full-time and three part-timers.

“In our city, for some reason, there’s a mindset that we should have eight full-time officers,” Martin said. “Eight full-time officers would be 320 hours a week” of coverage. “If you take the six full-time and three part-time, it comes to 315 hours, I think, a week. However, we’re saving tens if not hundreds of thousands of dollars by doing this.”

Part-timers help the city avoid paying larger health care, retirement and other overhead costs, he said.

One of Callery’s main campaign promises was eight full-time officers. Another pledge was a more peaceful city government.

“A lot of people say, ‘Ah, you don’t really need that many (police in Villa Hills),’” Callery said. “But you really do, because if you want 24-hour-a-day service, you really need that many.”

“We’ve talked about the seventh officer full-time, and I think he has the support to do that,” Koenig said. “I don’t see that to be an issue at all.”

On the other hand, an “eighth officer can be a little dicey,” she said. “Two part-time officers, if you have those, you actually get more patrol hours from two part-time than you do one full-time, just 40 hours a week.

“Again, with the city being the way it is, I think everybody knows and understands that we need money for roads,” Koenig said. “So the question is do you put that money you save from an eighth officer and have two part-times, instead of one full-time, and put that money toward roads? I think those are choices this council has to make.”

Martin said he hopes Callery will actually break his campaign pledge of eight full-time officers because Villa Hills can get more police coverage around the clock using part-timers, at lower cost.

“There’s always comments made, ‘Part-timers don’t care as much,’” Martin said. “If part-timers don’t care as much, why are so many other departments in the state going to part-timers?”

Callery said he is impressed by the vast experience of those now on the city’s police force, many who have served decades elsewhere, led by Police Chief Bryan Allen, who was a captain in Covington.

“I’ll bet there’s at least 200 years of experience among these guys, in Villa Hills,” Callery said. “Because they’ve retired from other departments, after 20 years in some cases.”

Callery, who was considered a consensus builder in Covington, also wants the city to explore ways to improve Villa Hills’ roadways, a big issue in the city.

“One of the things I proposed, and we’re actually going to get somebody in at our February meeting, was how to finance that,” Callery said. “Because there’s a lot of work that needs to be done on our roads. And I had suggested perhaps a bond issue, and using Kentucky municipal aid money we get, and maybe some other fund, to fund that.”

He hopes to have an expert on the process “to explain to council what that would involve. And then we could probably take a big chunk out of the road improvements,” he said.

Before Valentine’s Day in 2004, Callery created a whimsical program to take a tiny chip out of Covington’s gigantic pothole problem: Lovers could “adopt a pothole” and their honeys received photos of potholes surrounded by spray-painted pink hearts. The idea made international news and the mayor’s office regularly received calls from a rock disc jockey broadcasting in the United Kingdom.

“I hadn’t thought about that, but that was a fun thing,” Callery said. “At the time it was fun.” But: “Probably not in Villa Hills.”

If Callery follows his Covington trend, Villa Hills will add more historical markers. Covington added 26 during his time there.

Because the couple kept their home number from Latonia, they still get questions about who to call at Covington City Hall for a certain problem. Even department heads call to search his memory about things like an early-1980s access-road easement that helped ambulances reach residents on 33rd Street.

And even as a Villa Hills resident, he makes his weekly Saturday trip to the Kroger in Latonia.

“Still do that,” he says, with a laugh. “I know a lot of people who work there and I see a lot of my old friends there. So Joyce kids me about it, going down to Krogers. But that’s just remembering old times.”

Better moods possible

After talking with his new council colleagues, Callery expects good relations.

“We might disagree on some things, but I think we’ll do it in a civil manner. There is always going to be disagreements on different issues. I mean, the only one you never read about is Fort Thomas.”

And Fort Thomas, “they don’t really have any big issues – just deer,” he said, chuckling.

There will be at least some lingering news from past years, because, “There’s still some lawsuits that are out there, in the courts,” he said. “We have no idea when they’ll be resolved.”

There hasn’t been a council meeting yet. The first, a caucus session, will happen 6:30 p.m. Wednesday at 719 Rogers Road. Regular meetings likely will be scheduled for the same place and time after that on the third Wednesday of each month.

“I think (Callery) is a calming factor,” Koenig said. “He’s got a very low-key personalty, from what I can tell, and I think that showed in Covington. I think it’ll be nice for the city to see what he can do. He’s coming from a very big city to a very small city.”

She and Callery both are very complimentary of the city’s staff. As for the political mix, “I think all will be good,” Koenig said. “It’ll just be different. It’ll take us a while to all get to know each other and figure out what makes us all tick.”

“Hopefully,” she said, “we’ll have some fun along the way, and all is good.”

“Our public works is only three people,” Callery noted. He’s impressed with Public Works Director Buck Yelton: “Just on snow removal, they’re absolutely tremendous. They go out and they get your streets cleared. It’s fantastic. I mean, for a three-man force, they do a mountain of work.”

Callery appoints members to the fire authority that oversees the Crescent Springs/Villa Hills Fire Department. This year he has picked two council members, Scott Ringo and George Bruns (Bruns has done volunteer work for the emergency squad); as well as former council members Jim Cahill and Rod Baehner.

The city recently requested proposals for legal services and nine lawyers or firms applied. While Callery gets to select the firm, he will give council information about each firm and its experience, hoping to get strong consensus before he chooses. “I’ll be really open, so they have a good idea what’s going on.”

He has appointed four certified public accountants to the city’s finance committee, which will review Villa Hills’ budget and make recommendations to him and council. New council member Gary Waugaman will be chairman while former council members Jim Cahill and Amy Balson also will serve.

The city also will add more information to its web site to keep residents informed, Callery said.

Quick facts:

‣ Villa Hills has a total budget of $3.09 million.

‣ Villa Hills was incorporated as a sixth-class city in 1962. It now ranks among Kentucky’s fourth-class cities, with 7,300 residents. Covington, which this year is celebrating its bicentennial – an event Callery, a Northern Kentucky history enthusiast, had hoped to lead. Covington is a second-class city, with 40,500 citizens.

‣ Villa Hills’ 1 percent payroll tax brings in about $225,000, mostly from people working in schools there, or about 8 percent of the total budget. Half the budget comes from property taxes.

‣ Villa Hills has probably a dozen small stores within its 3.65 square miles. Covington has many times that number within its 13.2 square miles.

I am in complete agreement with Mary Lyons. How nice to see Mr. Rutledge covering the local landscape again, as well as Butch Callery’s smiling face in local government. Can’t wait to see what’s next.

It was good to see Mayor Callery in Latonia Krogers today. He was enjoying himself greeting “old friends”.

It made my day to read a story about Mayor Butch Callery written by Mike Rutledge. It was an honor to work with Mayor Callery in Covington. I was totally impressed by him as a Mayor, leader, friend, and all around very nice man. I was also a pleasure to know Mike Rutledge during those years. He too is a wonderful, honest, great man, and a fabulous writer. It is such a pleasure to see both Butch and Mike doing what the do best. Carry on, guys. As always, you are ahead of your game.