Whenever my Aunt Marge ventured an opinion on parenting, Uncle Jim shot her a withering glance and quipped, “There’s nothing like advice from a childless wife.” Instead of snapping back at him, she held back a retort by pursing her lips, swallowing whatever defense she might have mustered.

Marge was a trained nurse, after all, with a unique combination of restraint, common sense and compassion. My sisters and I loved when she came to visit, but for all we cared, she could have left the old man home. We thought she would have been a wonderful mother, but the problem parent in their pairing would have been crabby Uncle Jim.

As Mother’s Day approaches, many childless wives – myself included – steel themselves for an unwitting onslaught of thoughtless comments. We are told how lucky we are to have escaped two o’clock feedings, teething, and teenagers. We are reminded how much busier mothers are than the rest of us barren beauties.

Never to be soccer moms, we are ignored as a demographic, and lately some have even suggested that our marriages are a sham, since no offspring were produced from the union.

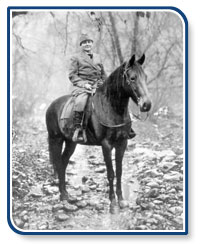

As far as I’m concerned, it is time to sing the praises of non-mothers, and pay tribute to the women who never held the title, “Mother,” (or were unable to claim it for very long). A case in point is Mary Breckinridge, an inspiration and über Mom, who founded the Frontier Nursing Service in 1939 when the first two students enrolled in her school of midwifery in rural Hyden, Kentucky.

Born into a wealthy and well-connected family, Mary Breckinridge grew up in Russia, where her father served as ambassador in the mid-1890s. She learned about midwives there, when her younger brother was born. Two fancy doctors hovered at her mother’s side, but it was the midwife who did all the work.

“Afterward,” Mary Breckinridge wrote, “my mother told me that when the baby was born the two doctors stood by in their white coats while Madame Kouchnova did the delivery. It was a normal delivery and there was no reason why they should interfere. I recalled this often,” she concluded.

Her mother’s experience stayed with Mary, even during her fine, classical education. She attended a Swiss boarding school where the girls were required to speak French only from Monday through Saturday, and completed her preparation to become a genteel, wealthy wife at a finishing school in Connecticut.

Mary Breckinridge did marry at 23, to Henry Ruffner Morrison, a lawyer from Hot Springs, Arkansas, but he died a year later from appendicitis. Instead of surrendering to grief, she began classes at St. Luke’s Hospital School of Nursing in New York and graduated in 1910. Although her dream was to apply her skills to the suffering of children, she felt compelled to return to Arkansas to care for her ailing mother. During this time, she met her second husband, Richard Thompson, and married him in 1912.

The marriage was not a happy one, but the couple had a little boy in 1914. Two years later, Mary had a baby girl, Polly, who was born prematurely and died six hours later. Another tragedy occurred in January 1918, when her son fell ill and died of a massive abdominal infection.

Thirty-seven, childless and eventually divorced, Mary traveled to France to assist the thousands of mothers and children affected by the war. She was appalled by conditions there, including starvation, ill health and mothers too weak to care for their children. As a result of this experience, she set herself on a course to devote her life to the care of mothers and babies.

Training as a nurse-midwife in England and Scotland prepared her to come back home and start the Frontier Nursing Service in Hyden. She recruited trained midwives from England to serve the needs of mountain families, but that became unsustainable in the 1930s, with Britain already at war and English nurse-midwives returning home. The focus of FNS shifted to recruiting American nurses to train as midwives.

There is much more to this story and Mary Breckinridge’s heroic and visionary role. Frontier Nursing University continues to play a crucial role in extending its outreach while cleaving to its core values of caring for women and families.

All this, thanks to Mary Breckinridge, a “childless wife.”

For more information, log on to www.frontier.edu. In addition, there is a riveting chronicle of the school, Mary Breckinridge and the nurses “whose journeys of discovery are recounted within its pages.” The title of the book is “Rooted in the Mountains, Reaching to the World: Stories of Nursing and Midwifery at Kentucky’s Frontier Nursing School, 1939-1989.”

Constance Alexander is a faculty scholar in the Teacher Quality Institute at Murray State University. She is also a freelance writer.