Nearly eight months after state lawmakers passed legislation to attack heroin use, three local health departments have embraced one of the more debated elements of the omnibus bill by opening needle-exchange programs for addicts.

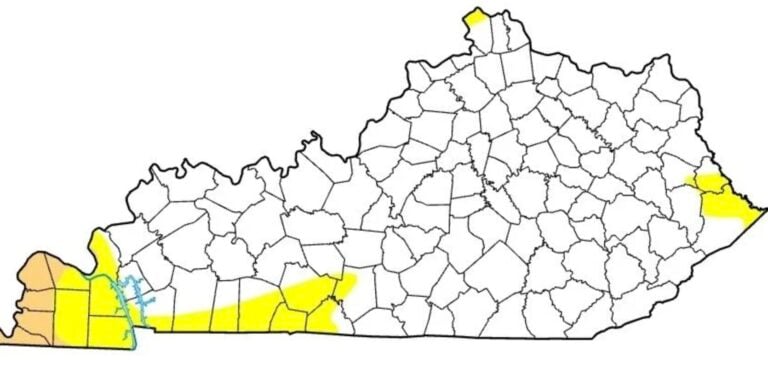

The exchanges are in the state’s two largest urban centers, Louisville and Lexington, and one of its most rural communities, Pendleton County, according to a presentation given on Monday to a legislative panel, known as the Senate Bill 192 Implementation Oversight Committee. Members heard how the approaches taken by health officials running the exchanges have varied about as widely as the geographical, economical and social differences of each of those communities.

“It is working slowly. Those with gray hair will remember the flight path of a D.C. 3 – slow but gradual takeoff.”

— Lexington-Fayette County Health Department Director Dr. Rice Leach

Lexington-Fayette County Health Department Director Dr. Rice Leach said his exchange only gives out a clean needle if a dirty needle is turned in. That exchange has collected 2,104 dirty needles and handed out 1,976 clean needles since opening on Sept. 4.

“In a word, we are doing pretty much what you said,” Leach said in reference to a debate on whether the legislation intended one-to-one needle exchange or just encouraged it. “If you don’t bring needles in, you don’t get needles back.”

Critics of Lexington’s approach said health officials wouldn’t be able to get enough dirty needles off the streets to effectively curb the spread of diseases since addicts often share one needle among themselves.

“It is working slowly,” Leach said on Monday in response to that qualm. “Those with gray hair will remember the flight path of a D.C. 3 – slow but gradual takeoff.”

Lexington’s exchange has served 104 people with 52 returning for at least a second visit, Leach said. Five people have been screened for HIV. Nine people have been referred for treatment for sexually transmitted diseases such as hepatitis.

Leach said none of the people who have visited the exchange have followed up with a drug abuse consultation. He said the major challenge that remains is convincing the intravenous drug users to get treatment for their addiction.

Louisville Metro Department of Public Health and Wellness Interim Director Dr. Sarah Moyer said her city adopted a need-based needle distribution program where exchanging dirty needles is allowed but not required.

When the exchange in Louisville opened in June, Moyer said health workers were giving out nearly nine clean needles for every one dirty needle collected. The ratio of syringes distributed to syringes returned has steadily decreased since then to a little more than two needles for every one needle collected.

“We have had a little different experience … than other counties,” Moyer said.

Critics of Louisville’s approach said that it amounted to a tacit endorsement of drug use while undermining one goal of the law – reducing the number of needles on the street. A goal of the anti-heroin legislation had been to decrease the risk of people getting stuck by improperly discarded needles – a particularly acute problem among police officers.

Moyer said there have been 1,102 participants in the exchange with 42 percent returning. Health workers have referred 64 people for drug treatment.

Pendleton County’s needle exchange hasn’t had one participant, said Three Rivers District Health Department Public Health Director Georgia Heise, adding that wasn’t because of a lack of need.

“It is everywhere,” she said in reference to heroin. “There is nobody in our area that hasn’t been effected in some way or another. It is not like something that is happening to somebody else.”

When panel co-chair Rep. Denver Butler, D-Louisville, asked why no one has used the needle exchange, Heise attributed the lack of participation to erroneous posting on social media that the exchange was an elaborate sting by police.

“I think we are overcoming that a little bit,” she said.

Northern Kentucky Independent Health District Director Dr. Lynne Sadler would like to set up a needle exchange, but she hasn’t received all the necessary approvals in her district’s region – Boone, Campbell, Kenton and Grant counties. She said Williamstown may be the closest to opening an exchange but Grant County Fiscal Court hasn’t granted the required approval.

“As you well know, this is a controversial issue and so our elected officials really want to delve into it and really understand the program, the depth and breadth of what the program is, and what the program is trying to accomplish,” Sadler said.

She said you can’t run an effective program without community support.

“A tremendous amount of time has been spent in trying to educate the community, as well as the elected officials, about what the program is and trying to garner formal support from a number of sectors of the community,” Sadler said.

Butler said he looks forward to seeing legislation to address the challenges of getting addicts treatment.

“We are doing a fantastic job of identifying addicts … and we are not doing such a good job getting them the care they need to them,” he said. “I wish there was an easy fix.”

It was the last meeting of the anti-heroin bill implementation oversight committee.

From Legislative Research Commission