By Paul A. Tenkotte

Special to the NKyTribune

If you’re like me, as the Christmas season approaches each year, my mind turns towards those less fortunate. Perhaps it is the approach of colder weather that makes us think of the poor and homeless, and the deprivations that they suffer on cold and lonely streets. And perhaps for some, it is something else entirely.

As a young child, I was fascinated by anything old. Our family had a beautiful antique nativity set, made in Germany of papier mâché and hand-painted. It bore the test of time. The set of cotton sheep with wooden matchstick legs, also made in Germany, was largely missing their tails. My father, as a child, had played with them. The damage and the repairs made to many of the nativity figures were all the more special to me, as there was a story behind each and every blemish.

As a college student at Thomas More, I took the opportunity to enroll in Old and New Testament classes. Those courses, and further reading and study since, have connected several dots for me: Christmas and the nativity, poverty, and homelessness.

In today’s technical parlance, Joseph and Mary were homeless (that is, “precariously housed”) on their visit to Bethlehem to enroll in the Roman census. Perhaps Joseph’s extended family in Bethlehem had no room for them to “double up,” or perhaps he had no extended family remaining there. The nativity story itself is an account of the divine touching the lives of the poor. Angels announced Jesus’ birth to shepherds, who were—during that time period—regarded as the poorest of the poor, often ritually unclean, and, as nomads, virtually homeless. Further, as an infant, Jesus and his parents became homeless refugees, fleeing to Egypt.

Living in a large metropolitan area of 2.1 million people, all of us in Northern Kentucky and Cincinnati encounter poverty and the homeless on a regular basis. However, if you’re like me, we often tend to cast our eyes away from the poor, not caring to connect with them — treating them as nameless and anonymous faces passing us on city streets.

Fortunately, concerned people and organizations in our community are working to tackle poverty and homelessness.

On Thursday, December 10th, I attended the Northern Kentucky Forum at the Kenton County Public Library in Covington. The topic was “Homelessness: Examining Causes, Finding Solutions.” Guest speakers included: Kevin Finn, president and CEO of Strategies to End Homelessness; Kim Webb, executive director of the Emergency Shelter of NKy; Linda Young, executive director of Welcome House; and Kelly Blevins, court liaison and homeless education coordinator of the Kenton County School District.

Throughout our regional history, our ancestors tried to tackle the problems of poverty and homelessness. When our communities were young, and nearly everyone knew one another, it wasn’t possible to merely ignore the poor. First and foremost, family members and friends were called upon to care for the indigent, the ill, and the aged.

But what if someone had no family? Then, following the lead of the old English Poor Laws, counties in Kentucky provided “outdoor relief” for the poor in the early 19th century. “Outdoor relief” does not mean that they left people outdoors! Quite the contrary, “outdoor relief” meant that the counties did everything in their power to keep people in their homes. In other words, they would provide food, fuel and small amounts of cash so that the needy would not starve, freeze, or have to move from their places of residence.

As the 19th century continued, and population increased, the provision of “outdoor relief” began to be replaced by large institutional buildings called “poorhouses.” There, the indigent poor and the very sick—all of whom had no one else to care for them—were forced to live together in dormitory-style arrangements. Very often, poorhouses were located in rural areas, and the able-bodied inmates worked on the poorhouse farm.

By the mid-to-late 19th century, poorhouses nationwide began to gain a very bad reputation. Often, they were poorly managed, dirty, and of course, they mixed women with men, young with old, and the healthy with the sick. It was a failed recipe from the start.

Kenton County operated a poorhouse in Independence, and the City of Covington had a so-called pesthouse, sometimes called the Branch Hospital or Lazarus Hospital, on Kyles Lane. Operated by the city’s board of health, the pesthouse cared for the sick poor. Containing nine acres, it was sold to the county in 1903.

By the early 20th century, enlightened Kenton County officials knew that poorhouses and pesthouses didn’t work. So, in May 1907, they opened a state-of-the-art infirmary. Later called Rosedale Manor, the four-story brick building was a vast improvement over the poorhouses of the past.

Of course, the late 19th century saw the development of a number of other specialized institutions to help the poor and children. Some of those children were orphans. Others were neglected or abused. Still others had only a single parent, who needed to work fulltime. And finally, some families simply needed an institution to care for their children in the short-term, while they got back on their feet after an illness or unemployment wrecked the family’s finances.

The St. John’s Orphan Society of Kenton County was founded in 1848. For a number of years, it did not operate an orphanage, but instead placed orphans with worthwhile families. Later, it opened an orphanage in Covington, and still later, in 1868, purchased the 55-acre St. Aloysius Seminary property on the outskirts of Covington (today’s Diocesan Catholic Children’s Home on Orphanage Road in Ft. Mitchell).

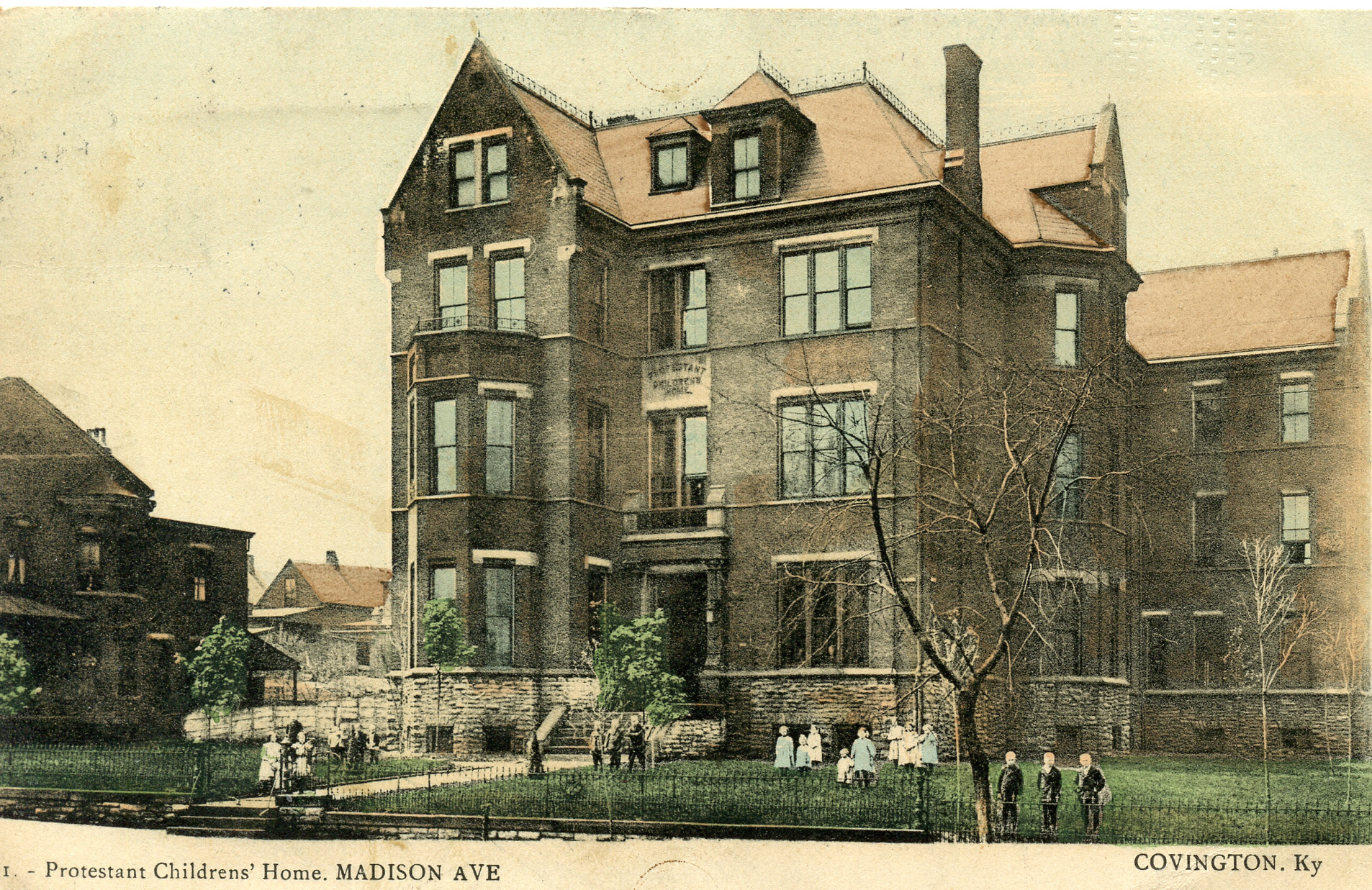

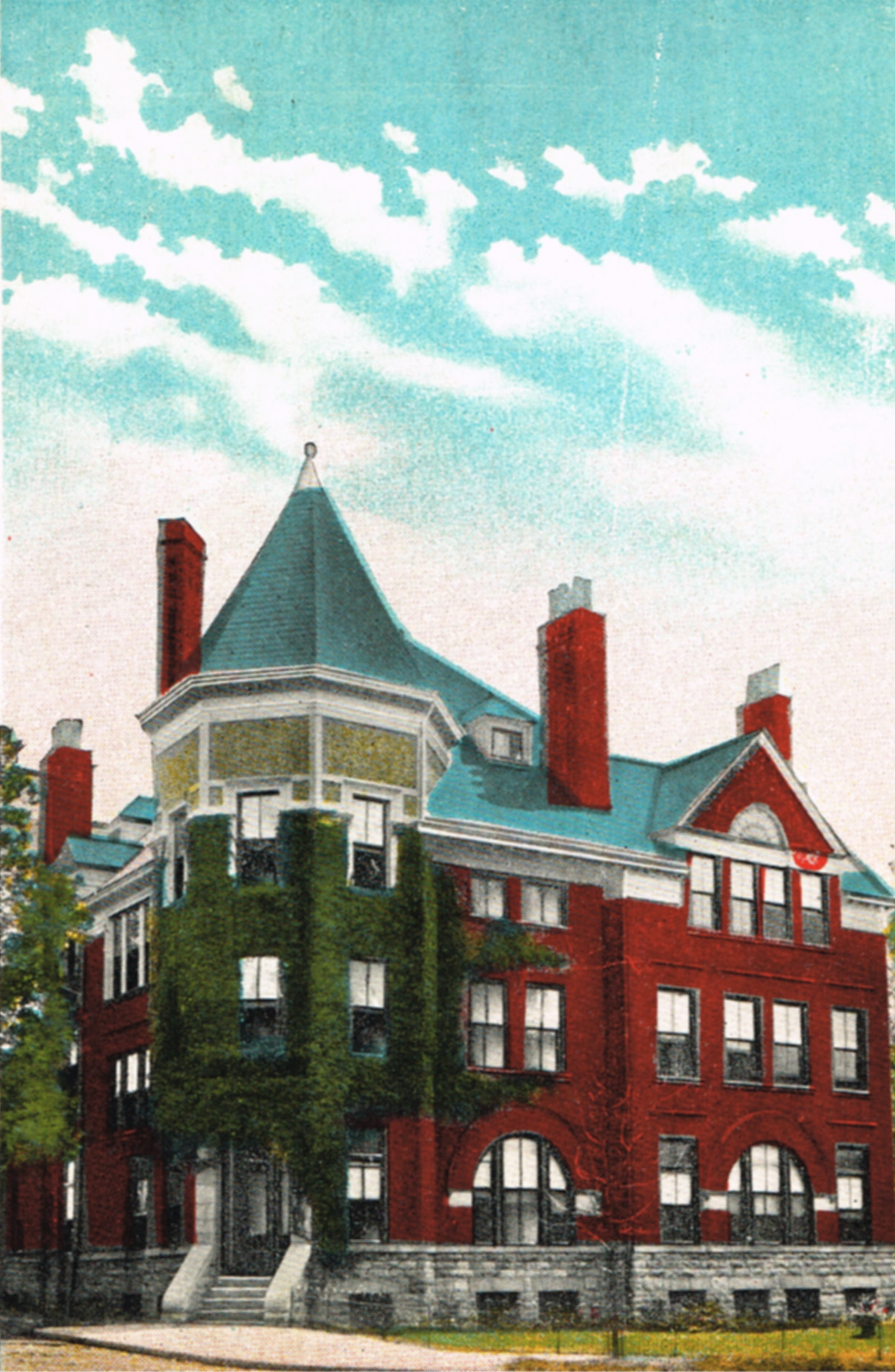

Businessmen and philanthropist Amos Shinkle (1818-92) was concerned for poor Protestant children. In 1880, he and others chartered the Covington Protestant Children’s Home to care for “the friendless, homeless, unprotected children or orphans.” An impressive orphanage, designed by the talented architect, Samuel Hannaford, was opened in 1882 at 14th and Madison in Covington. In the mid-1920s, the home moved to Devou Park in Covington, where it remains today as the Children’s Home of Northern Kentucky.

In 1886, concerned citizens established the Home for Aged Women and Indigent Women in Covington. Later renamed the Covington Ladies Home, it opened a stately building capable of housing 50 women in 1894 at 7th and Garrard Streets. It still operates today.

The face of poverty and homelessness today, unlike a century or more ago, tends to be more anonymous than ever before. Too often, we forget the interconnectedness of our communities and of our individual lives. But like that beautiful antique nativity set of my youth, there is a story to tell behind each and every blemish of all of us. And those stories are what make human history interesting and worth recounting.

Paul A. Tenkotte (tenkottep@nku.edu) is Professor of History and Director of the Center for Public History at NKU. With other well-known regional historians, James C. Claypool and David E. Schroeder, he is a co-editor of the new 450-page Gateway City: Covington, Kentucky, 1815-2015, now available at your local booksellers, the City of Covington, and online sellers.