First of a two-part series on white-tailed deer in Kentucky — pre-settlement, remnant deer herds, deer hunting prohibited and early restoration efforts.

These are arguably the “good old days” of deer hunting in Kentucky.

The 2015-16 season ended Monday with an all-time record harvest of more than 155,295 deer.

Thanks to decades of wise and careful management by the Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources, and generations of sportsmen who paid for the cost of restoration, Kentucky has a deer herd that is the envy of the region. Kentucky deer are healthy and robust, and the bounty of record-book antlered bucks produced has attracted the attention of hunters, and wildlife managers, from all over the country.

This past season was the third overall harvest record in the past four years, with hunters checking in a record 131,395 deer in 2012-13 and 144,409 deer in 2013-14. Every season since the 2000-01 season hunters have checked in more than 100,000 deer.

Hunters under the age of 35 may not recall a time in their lives that white-tailed deer weren’t a part of Kentucky’s rural landscape. But ask any older family member or friend that hunted deer in the early years of restoration, and you’ll get a much different story.

Hunters from the Baby Boomer generation, who started hunting deer in Kentucky as teenagers or young adults during the 1960s and 1970s, had to travel great distances just to see a deer. It was a time when this important native species was still absent from many counties in the state.

Pre-Settlement

The first long hunters, explorers and land speculators who ventured west of the Appalachians in the 18th century found a land that was rich in natural resources.

The land that would become Kentucky was bounded on three sides by major rivers, with five distinct physiographic regions, and more than 13,000 miles of rivers and streams teeming with fish and mussels. Old-growth forests covered 90 percent of the 40,395 square miles.

There were vast tall grass prairies, licks where salt water bubbled out of the ground, and an estimated 1.5 million acres of wetlands. In the rolling land of the interior, park-like savannas stretched for miles, with clusters of burr oaks and blue ash trees interspersed by grasslands, and vast stands of river cane.

There were thundering herds of bison, black bears, wolves, majestic woodland elk, and white-tailed deer in seemingly every forest opening. Frontier hunters harvested deer for their skins to make clothing, and relished venison backstraps and hams cooked over open fires.

Remnant Deer Herds

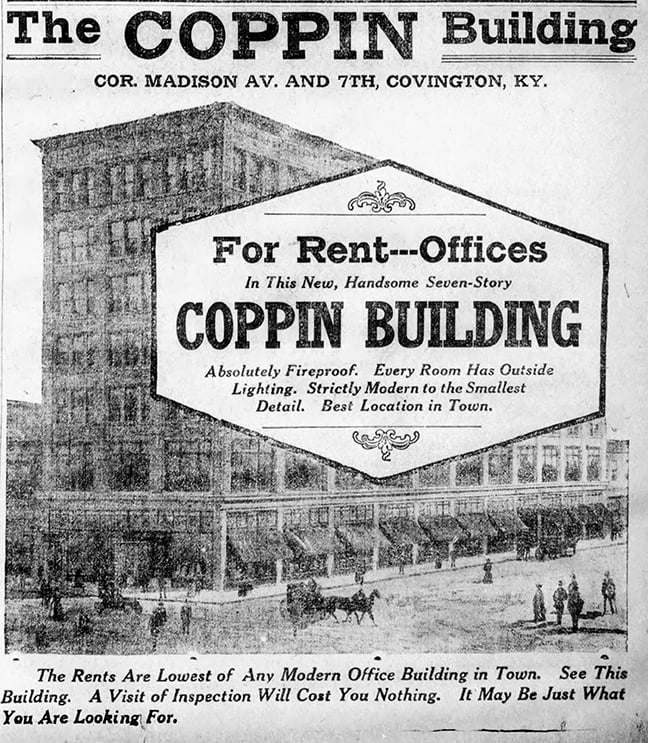

But more than a century of habitat destruction and subsistence hunting by 19th century settlers took its toll on local herds. Deer numbers crashed. By 1915 deer were absent from most of Kentucky, except for remnant herds in a handful of counties in western Kentucky.

It would be 84 years before deer restoration efforts would be complete in all 120 Kentucky counties.

Upon recommendation of the Division of Game and Fish, the Kentucky General Assembly prohibited deer hunting in 1916. Deer hunting in Kentucky would not resume until 1946.

Early Restoration Efforts

In his biennial report, dated Oct. 1, 1917, Executive Agent J. Quincy Ward, of the Kentucky Game and Fish Commission, reported that “deer imported from Michigan and New Jersey were liberated in an enclosure on Pine Mountain in Bell County and at the State Fair Grounds in Louisville. Pine Mountain deer increased to 48 and will be distributed and liberated during the late winter months.

“Deer at Louisville, 26, have increased splendidly and as the enclosure is small it will be necessary to liberate at least two-thirds of them from that enclosure.”

The remnant deer herds in western Kentucky got some new blood in 1919 when the Hillman Land Company acquired 30 white-tailed deer and 20 fallow deer from Wisconsin and released them on its land holdings between the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers, in modern-day Lyon and Trigg counties.

By the early 1940s, the deer herds scattered throughout Caldwell, Christian, Lyon, and Trigg counties, in western Kentucky, had increased to about 2,000 animals.

But the first legal deer hunt in 30 years was not held in western Kentucky.

The controlled hunt was held near Bardstown, on Bernheim Foundation property and surrounding counties, on Jan. 2-14, 1946. Successful hunters were required to buy a $15 tag.

In 1946, state wildlife managers initiated a three-pronged restoration plan to restore white-tailed deer in Kentucky.

First, a series of refuges would be established, then deer would be live trapped from existing populations and transported to WMAs for stocking, and thirdly, habitat improvement work would be done on lands where deer were to be stocked. This included the creation of wildlife woods openings, water holes, and food plots.

Thirteen refuges were set-up across the state, 11 on federal or state-owned properties, and two on private lands.

Deer Trapping and Relocation

Deer trapping and relocation began in 1947, and the 77 deer were captured at Kentucky Woodlands National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) and Jones-Keeney Wildlife Management Area (WMA), were released on Beaver Creek WMA, in McCreary and Pulaski counties; Kentucky Ridge State Forest, in Bell county; Mammoth Cave National Park, in Edmonson and Hart counties, and Pennyrile State Forest, in Caldwell and Christian counties.

By the mid-1950s, deer restoration efforts shifted to establishing herds on a statewide basis, including privately-owned lands wherever suitable habitat was present.

It would take decades to translocate deer to all 120 counties.

Just seven years into restoration efforts, deer numbers had increased sufficiently on Mammoth Cave National Park, and Pennyrile State Forest, to allow live trapping. Deer are relocated to Estill, Jackson, Lee, and Menifee counties.

In 1955, bottomlands along the lower Ohio River in Ballard County were purchased to establish a wintering area for migratory Canada geese. A total of 8,373 acres were bought for $433,000, using department and matching federal funds.

But over time, the new Ballard WMA would prove to be just as important to Kentucky’s deer restoration efforts as to migratory waterfowl. Deer live-trapped at Kentucky Woodlands NWR are released on Ballard WMA beginning in the late 1950s.

Herd Growth and Expanded Hunting Opportunities

The number of Kentucky counties open to deer hunting continued to increase, with the growth of the state’s deer herd.

By the 1962 season, 43 counties were being hunted, and nearly 14,000 hunters took part. About 5,000 deer were harvested.

For more outdoors news and information, see Art Lander’s Outdoors on KyForward.

Deer trapping and translocation continued, with counties stocked with a minimum of 50 to 75 animals. Additional deer, usually 50, were transported to counties when initial stockings appeared unsuccessful.

In order to give the newly released animals time to become established and populations to increase to huntable levels, deer hunting was closed in these newly-stocked counties for at least five years.

In 1964 Kentucky Woodlands NWR is incorporated into the newly-created Land Between The Lakes National Recreation Area (LBL), managed by the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA).

By the early 1970s, LBL’s deer herd was huge, offering some of the best hunting in the state. Archery season is particularly popular because it was an open hunt, and archers from all over Kentucky crowded the area’s many campgrounds for the opening of bow season each fall.

After 1965, Mammoth Cave National Park and Ballard WMA become the two main sources of animals for Kentucky’s deer restoration efforts.

The best hunting was often on public hunting areas. In 1965, 51 percent of the statewide deer harvest occurred on Ft. Knox. By 1968, it had dropped to 46 percent, as the deer statewide herd continued to grow.

Next week: statewide archery season, mandatory hunter orange and deer check stations, high-density stockings, deer population models, large herds and record-book antlered bucks, and today’s era of record harvests.

Art Lander Jr. is outdoors editor for NKyTribune and KyForward. He is a native Kentuckian, a graduate of Western Kentucky University and a life-long hunter, angler, gardener and nature enthusiast. He has worked as a newspaper columnist, magazine journalist and author and is a former staff writer for Kentucky Afield Magazine, editor of the annual Kentucky Hunting & Trapping Guide and Kentucky Spring Hunting Guide, and co-writer of the Kentucky Afield Outdoors newspaper column.