By Berry Craig

NKyTribune columnist

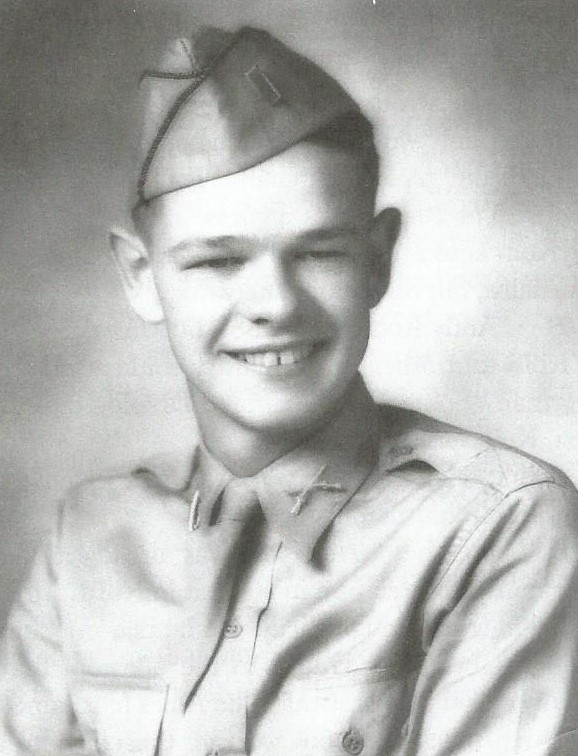

First Lieutenant Frank Kolb and his infantry company went down in history as the first U.S. troops “to set foot on German ground” in World War II.

The western Kentuckian never claimed credit for the feat. “It was a good day anyway,” he said in a 1999 interview. “I didn’t lose anybody.”

Kolb died in 2000 at age 77. He was retired from Kolb Brothers Drug Co. in Paducah, his family’s business.

A Paducah native who moved to Mayfield after the war, Kolb earned four Silver Stars, a Bronze Star and a Purple Heart in seven campaigns with the First Infantry Division. He might have been the youngest company commander ever in the storied “Big Red One.”

Kolb was 21 when he fought his way through the Siegfried Line, Adolf Hitler’s vaunted defense barrier, and trod German soil near Aachen. The date was Sept. 13, 1944.

Kolb made headlines in the Stars and Stripes, the GI newspaper. “The story also got in The New York Times and a lot of other papers,” he said.

Kolb got in a history book, too.

“Kolb’s men were the first American soldiers to set foot on German ground,” wrote Irving Werstein in The Battle of Aachen. “At least my name was spelled right in the book,” Kolb said, grinning. “It was wrong in all of the papers.”

When Kolb and his men breached the Siegfried Line, a Stars and Stripes reporter interviewed the young lieutenant. He got the story right, but not Kolb’s name.

“After ten years of talk about the Siegfried Line, 21-year-old 1/Lt. Bob Kalb, of Paducah, Ky., took his company through it without a casualty,” the reporter wrote. “Since Kalb and his men forced the first opening, the armored unit working with this crack infantry division has been pouring through the gap.”

Lt. “Kalb” told the reporter, “We knocked out about 15 or 20 pillboxes, I guess.”

Kolb kept a clipping of the Stars and Stripes story. The reporter was a famous journalist after the war, but on national network TV.

He was Andy Rooney of CBS’s “60 Minutes.”

Kolb said other First Infantry soldiers may have beaten his outfit into Germany. Some Third Armored Division tank crews claimed they were the first, he remembered.

“What does it matter who was first?” Kolb asked. “I didn’t think it was that important then. I still don’t.”

By September, 1944, Kolb was already a battle-hardened veteran. The Germans captured him in combat in North Africa, but he escaped.

He fought through Sicily. He landed on Omaha Beach on D-Day and then fought across France to the German border, guarded by what the enemy called the “Westwall.” The Allies nicknamed it the “Siegfried Line.”

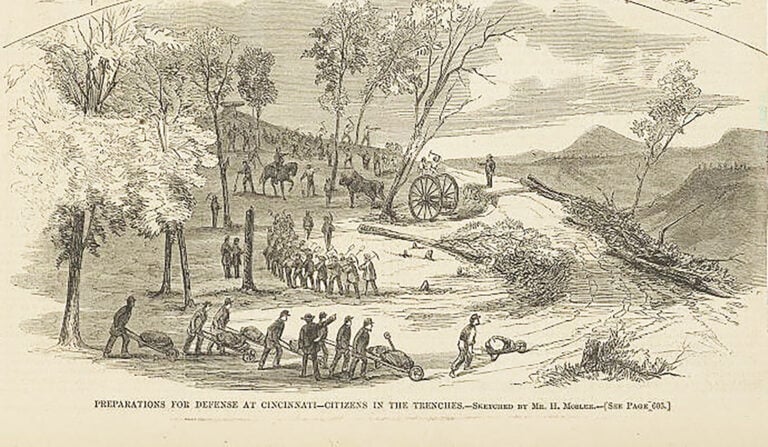

Three miles deep on average, the concrete and barbed-wire bulwark bristled with “hundreds of mutually-supporting pillboxes, troop shelters and command posts,” wrote Charles B. MacDonald in his book The Mighty Endeavor.

“Where no natural antitank obstacle existed, German engineers had constructed pyramidical concrete projections called ‘dragon’s teeth,’ draped in parallel rows across hills and valleys like some scaly-backed reptile.”

Similarly, Rooney described the wide defense belt as “a series of strategically-placed pillboxes. In the hilly country of the border, roads run through the valley, and the Germans placed the fortified concrete igloos in positions which commanded the only possible entry for vehicles. On both sides of the roads, concrete ‘dragon’s teeth’ extended for miles, preventing tanks from rolling over the open country between the road networks.”

When Kolb and his troops attacked on the morning of Sept. 13, they were out front in “a general offensive along every mile of the Westwall from Holland to Switzerland,” Werstein wrote. Kolb and his men ducked and dodged through the dragon’s teeth, meeting unexpectedly light enemy resistance.

“The line would have been tough to crack if the Germans had had enough men to man it the way it should have been,” Kolb suggested to Rooney.

Even so, Kolb knew he needed armor to knock out the German “igloos.” A platoon of tank destroyers — Sherman tank-like vehicles with open-top turrets and powerful guns — got the job done.

“Our… [tank destroyer] fired at some of them from about 20 yards and blasted them wide open,” Rooney quoted Kolb. “They’d roll right up and fire a 90-millimeter shell through the aperture,” Kolb recalled 55 years later. “The back door would fly open, and the Germans would come running out. They found a woman with one group, a good-looking blonde.”

Sometimes, Kolb said, the Germans surrendered as soon as a 31-ton tank destroyer pointed its long-barreled gun at their pillbox. “The ordinary German soldier had enough sense to give up when he knew he was beaten.”

After a while, the rest of Kolb’s battalion passed through his company. He remembered talking to Don Whitehead of the Associated Press, another famous war correspondent, in a break from battle. “I was just glad none of my men had been killed. I don’t think any of them had even been wounded.”

“Skippy” Skinner, Kolb’s buddy from Paducah, wasn’t so lucky. By chance, Kolb spotted him in another company that moved ahead of his outfit.

“I told Skippy, ‘Don’t forget to duck,’” Kolb said. A German tank shell killed Skinner hours later.

Werstein said that by punching through the Siegfried Line and capturing Aachen, the Americans won a great victory, “a harbinger of what was to befall the [German] nation whose people and leaders had dreamed of ruling the world.”

But an infantry soldier doesn’t always know when a battle is won, said Kolb, who made captain before he turned 22. He fought in the Huertgen Forest, the Battle of the Bulge and other bloody combat before the Allies officially celebrated the Nazi surrender on May 8, 1945.

“My little walkie-talkie could pick up the BBC [British Broadcasting Corp.] if I was up high enough,” he said. “I remember climbing up on this hill in Sicily and hearing all about ‘the victorious American army.’ We’d had the hell beaten out of us that day and hadn’t gained a thing.”

Berry Craig of Mayfield is a professor emeritus of history from West Kentucky Community and Technical College in Paducah and the author of five books on Kentucky history, including True Tales of Old-Time Kentucky Politics: Bombast, Bourbon and Burgoo and Kentucky Confederates: Secession, Civil War, and the Jackson Purchase. Reach him at bcraig8960@gmail.com