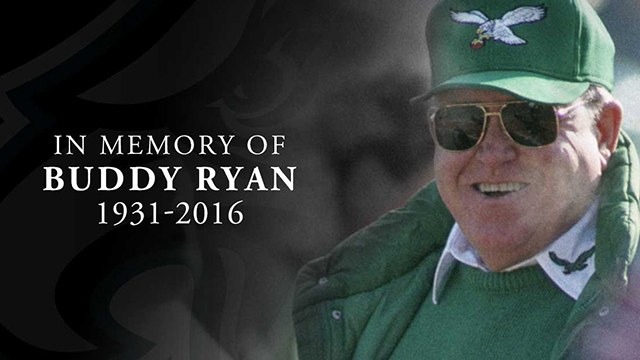

As various former players and fellow coaches lamented the recent deaths of Pat Summitt and Buddy Ryan, the narratives began to sound much alike. Their sports were different – college basketball for Summitt, pro football for Ryan – but both were remembered as “old-school” coaches who were tough but fair. They had leadership qualities that brought out the best in their players.

Neither seemed to be motivated by money, the force that drives today’s most successful coaches. They were more about teaching and reaching for the stars. They knew perfection is impossible, but that didn’t keep them from pursuing it. They lived to win, but never cut corners. They believed that success was possible only through hard work and sacrifice.

Of all Summitt’s records and achievements, her most impressive, at least in my opinion, is that she graduated every scholarship athlete who completed their eligibility at Tennessee. That’s right – every single one. Obviously, she was doing more than just winning championships and developing WNBA stars. She was teaching girls to be women. She was developing the national, state, and community leaders of tomorrow.

That’s what the greatest college coaches have always done.

Like Ryan, Summitt could be tough, grumpy, and demanding. She liked to say that she was a basketball coach, not a women’s basketball coach. She did not treat her players as if they were dainty little things. She treated them as what they were – world-class athletes who needed to be mentally and physically tough.

Summitt probably got along with the media better than Ryan. When she wanted, she could be charming, funny, and polished. With Ryan, though, what you saw was what you got. He was a football coach’s football coach. Ask Mike Ditka, the Chicago Bears head coach in the 1980s who clashed frequently with Ryan, his defensive coordinator.

But Ditka finally backed off and let Ryan run the Bears’ defense the way he wanted, and that turned out to be one of the smartest things he ever did. Although Ryan was egotistical enough that he wanted everyone to know that he, not Ditka, was responsible for the Bears’ defense, the head coach swallowed his pride and let Buddy have his own little personal kingdom.

Today, when NFL junkies begin to discuss the league’s greatest defenses, the 1985 Bears are mentioned early and often. Led by middle linebacker Mike Singletary, an extension of Ryan, the Bears overwhelmed opponents with their talent and schemes. After shutting down the New England Patriots in the 1986 Super Bowl, the defense carried Ryan off the field.

Even so, as accomplished as Ryan was, he never reached the iconic status that Summitt achieved long before he retirement in 2012 due to the onset of Alzheimer’s.

One national commentator said that only Billie Jean King belong in Summitt’s class when it comes to promoting the growth of women’s sports. She became the head coach at Tennessee in 1974, only two years after the federal government had mandated equality for women’s sports through Title IX, and she single-handedly built the Lady Vols into the first women’s program that was taken as seriously as the men’s program.

As a young coach making $250 a month, she washed the team uniforms and drove the bus on road trips. That’s a work ethic that a coach like Buddy Ryan could appreciate. She never asked for special treatment – only for the tools necessary to build champions.

In many ways, Summitt was to women’s basketball in the Southeastern Conference what Kentucky’s Adolph Rupp was to the men’s game. She won so much that the league’s other members had to upgrade their programs in the interests of being respectable and competitive. (Rupp, by the way, also graduated a high percentage of his players.)

She won eight national titles at Tennessee, twice as many as Rupp, and she coached the U.S. Olympic team to the gold medal in the 1984 Olympics. The men’s Olympic coach that year was Bob Knight of Indiana. Like Ryan, Knight also shared many personal and professional traits with Summitt. But she did a better job of smoothing the rough edges.

Interestingly, just as Knight followed Rupp’s teams while growing up in Orrville, Ohio, Summitt did the same as a farm girl in East Tennessee. Even as kids, they knew excellence when they saw it and they wanted to have it for themselves.

Years after the magic 1985 season, Ryan bought a horse farm near Lawrenceburg and was a Kentucky resident in his latter years. One of his last public appearances came last fall, when he and Muhammad Ali both attended a U of L football game as guests of Athletics Director Tom Jurich.

Summitt also had a U of L connection. She and the Lady Vols were the visitors in the very first athletics event held in the KFC Yum! Center in downtown Louisville.

“We wanted to play that first game against somebody really special,” said Cardinal head coach Jeff Walz. “Nobody was more special than Pat Summitt and Tennessee, and they were only four hours away. I’ll never forget her walking into the arena wearing that orange suit.”

Both Summitt and Ryan coached players with Louisville connections. U of L’s Otis Wilson was a starting linebacker on the Bears’ 1985 defense, and Louisville native Lisa Harrison was one of Summitt’s many All-Americans at Tennessee. (Harrison played for the Lady Vols from 1989-’93.)

Said Lisa’s dad, Cobby, a former star and manager of the Kentucky Bourbons professional softball team:

“They lost a game one time and I remember the girls coming out of the locker room and walking straight to the bus,” Cobby said. “No hugs, nothing. When they got home, they found their locker room had been locked up. ‘You don’t deserve to dress in there,’ Pat told them. So they went several days without a locker room. Lisa told me she changed clothes in a janitor’s closet. That was how tough she could be.”

If that story had ever been told to Buddy Ryan, he would have laughed in approval. That was “old school” at its best. Of course, today’s coaches couldn’t get away with stuff like that. Social media would explode, committees would be formed, lawsuits would be filed, policies made.

So what’s an aspiring young coach to do if he or she wants to be the next Pat Summitt or Buddy Ryan? Don’t kids still need discipline as much as they ever have, maybe more? Where’s the line between what’s socially acceptable and politically correct and what’s not? And doesn’t that line keep moving and shifting, almost daily?

Go back to the fundamentals. That’s the only answer. Be a teacher first and foremost. Be honest and have integrity in everything you do. Set boundaries and stick to them. Never make promises you can’t keep. Don’t coddle athletes, but treat them with respect. Emphasize brain power as much as muscle power.

At bottom, that’s the way Pat Summitt and Buddy Ryan both did it. You might say it worked out rather well for both.

Billy Reed is a member of the U.S. Basketball Writers Hall of Fame, the Kentucky Journalism Hall of Fame, the Kentucky Athletic Hall of Fame and the Transylvania University Hall of Fame. He has been named Kentucky Sports Writer of the Year eight times and has won the Eclipse Award twice. Reed has written about a multitude of sports events for over four decades, but he is perhaps one of media’s most knowledgeable writers on the Kentucky Derby