LOUISVILLE – Whenever I appeared on Milton Metz’s radio talk show, I checked out the United States map that dominated one of the walls in the famed “Metz Studio” at WHAS radio, the 50,000-watt station that still may be found at 840 on your AM dial.

The map was sprinkled liberally with pins stuck in every city from which Metz had received at least one call. Naturally, most of the pins were concentrated in Kentucky, Indiana and Ohio. But there were some stuck in places like Los Angeles, Las Vegas, Denver, and New York City.

That might not seem impressive in a day where just about any local radio show can be accessed from an app on a cell phone. But back then it was impressive, even awesome, because it showed the reach of a 50,000-watt station. When you went on “Metz Here,” you never could tell who might be listening.

I saw Metz’s map for probably the last time yesterday. It was among the photos and artifacts on display in front of the altar at The Temple, where maybe 100 or so gathered to honor the radio-TV icon who was 95 when he died on Jan. 12 of this year.

One of his former co-workers, Doug Proffitt of WHAS-TV, said Metz guarded his age so jealously that it long was a topic of speculation around the office. He remembered the day when Metz’s age – then he was in his late 80s or early 90s – suddenly appeared in a Courier-Journal story.

Immediately Proffitt called Metz.

“Milton,” he said. “I saw your age in the paper. What happened?”

“Sometimes, Doug,” said Metz, “you just have a bad day.”

Hired only because he responded to a newspaper ad, Metz rose to become a pillar of what was known as “The Bingham Media Empire.” Home-owned by Barry Bingham Sr. and his family, the empire included two newspapers (Courier-Journal and Louisville Times); a 50,000-watt radio station (WHAS 840), a TV station (WHAS-11), and a money-making machine that printed Sunday magazine sections for papers around the South (Standard Gravure).

When I was growing up in Louisville in the early 1950s, both WHAS-11 and rival WAVE-3 were heavy on local programming. It was a time when TV sets were becoming affordable for middle-class families.

So the stars of local TV became local celebrities. Along with Metz, WHAS had the likes of Ray Shelton, Phyllis Knight, Randy Atcher, Cactus Tom Brooks, and Pee Wee King; WAVE countered with luminaries such as Uncle Ed Kallay, Ryan Halloran, and Livingston Gilbert.

It was the era of black and white, both on the screen and in the studio. It wasn’t until somewhere in the 1970s, in fact, when the stations began hiring African-American reporters. At the newspapers and radio stations, it was much the same.

Like his colleagues, Metz did a little bit of everything – news, weather, sports, commercials. He first made an impression on the young men as a mustachioed villain – his name was McSnarly, or something like that – on the afternoon “T-Bar-V” show starring Randy and Cactus. Years later, he always seemed delighted whenever I’d bring up that role.

Although he did both radio and TV throughout his career, Metz found his niche in 1959, when Metz started doing a radio talk show called “Juniper 5-2385,” which later became “Metz Here.” His wit, intelligence, sense of humor, and inquisitive mind made him the perfect host.

Well, at least he was perfect for his day. Unlike the right-wingers who monopolize today’s talk-show market, Metz always was civil, respectful, and open-minded. He was a good listener and a good interviewer. And under no circumstances would he allow either his guests or his callers to become rude, crude, or demeaning.

At yesterday’s service, his son Perry talked about the time Metz did a show with a noted expert on sexual behavior.

“My husband and I have a good sexual relationship,” said one caller, “but there’s one thing that bothers me; he gets tired after three or four hours.”

Nobody remembers the sex therapist’s answer. But everyone who heard the show remembers the laughter that Metz literally couldn’t control.

When I joined the C-J fresh out of college in 1966, all the Bingham media properties were located in the building at 6th and Broadway. The newspapers were on the fourth floor, the radio station on the fifth, and the TV station on the sixth.

One night the news came over the Associated Press teletype machines that the Green Bay Packers had given up Louisville’s Paul Hornung to the New Orleans Saints in the NFL expansion draft. We were trying to get in touch with Hornung when it was learned he was in our building, doing the Metz radio show.

Earl Cox, who was in charge that night, told me to grab a notebook and go up to WHAS to get some quotes. Although Metz was getting a “scoop,” he graciously agreed to let me eavesdrop. That may have been the first time I met both Metz and Hornung, and I’m not sure which impressed me more.

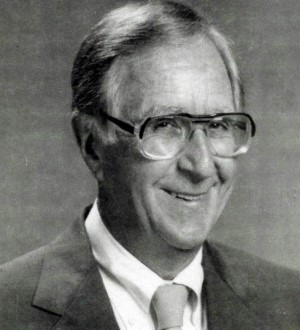

A gentleman has been defined as “a man who is at home in any company.” If that’s so, it fit Metz as his trademark glasses. He was urbane, witty, sophisticated, funny, and well-informed – the perfect dinner-party guest. But he was not a snob. Never. He enjoyed an earthy story as much as anybody, and he loved jokes, even if they were at his expense.

When Terry Meiners joined the WHAS840 team in the mid-1980s, he did a shtick about Metz’s image as a bon vivant. Instead of getting ruffled, Metz loved it to the point that he became one of Terry’s mentors and a regular guest on his afternoon drive-time show. Truthfully, from the first, Terry was in awe of Metz’s professionalism and presence.

He wasn’t a sports fan except for tennis, a game he played regularly with the late Courier-Journal general columnist Joe Creason at the park that bears Joe’s name. If I’m not mistaken, I think his beloved wife Mimi also shared his love of tennis. Heck, they shared everything. I can envision Milton telling her about his show with the sex therapist.

Although sports were not high on his list of interest, he kept up with what was going on in the sports world in order to relate to his listeners. I was honored to be one of his “go-to” guys whenever he felt the need to talk about a sports issue.

On Kentucky Derby Day, Metz’s assignment was patrolling ‘Millionaire’s Row” in the hopes of getting a few words with whatever celebrities happened to be attending the “Run for the Roses.” Since many of them already had been on his talk show at one time or another, they treated him like an old friend.

Once again, Proffitt:

“One year Walter Cronkite was coming and we needed to get in touch with him. I called Metz on the off-chance that he might know somebody who could help me. ‘Just a moment, Doug,’ he said. He came back and gave me Cronkite’s numbers in Manhattan and at his vacation home. ‘Wow,’ I said, ‘I had no idea you had the numbers.’ After a chuckle, Metz said, ‘Doesn’t everyone?’ That was Milton for you.”

Upon retiring in 1993, Metz turned over his radio show to Joe Elliott, who carried on in the Metz tradition for a number of years. But then the station fired Doug and replaced him with a high-decibel syndicated right-wing host who, sadly, is everything that Metz was not.

The Metz show was an important forum where community and state leaders were invited to explain their decisions and talk directly to the public in an atmosphere of civility. I have mourned its loss for years, because its absence has diminished our community dialogue and public discourse.

Now I also mourn the loss of the unique man who entertained us, informed us, and calmed us in times of crisis, such as the 1974 tornado. He also was a pillar of the “Crusade for Children” from its beginning in 1954 until he reached the age of…well, that was none of our business, was it?

About a year ago, I had breakfast with Metz, former WHAS radio morning host Wayne Perkey, and Ed Shadburne, who was one of their bosses. It was such a wonderful hour of laughing and reminiscing that it gave Metz an idea.

“I think I’ll see if I can get somebody to let us do a weekly radio show called ‘The Old Guys’ or something like that,” he said. “You (me) can be the youngest of the old guys. We’ll talk about whatever’s on our mind and give these young people today something to think about.”

Alas, the show never got off the ground. I would have loved being one of Metz’s sidekicks, and I’m sure I would have gotten him to reprise his villain’s role on T-Bar-V Ranch.

Billy Reed is a member of the U.S. Basketball Writers Hall of Fame, the Kentucky Journalism Hall of Fame, the Kentucky Athletic Hall of Fame and the Transylvania University Hall of Fame. He has been named Kentucky Sports Writer of the Year eight times and has won the Eclipse Award twice. Reed has written about a multitude of sports events for over four decades, but he is perhaps one of media’s most knowledgeable writers on the Kentucky Derby