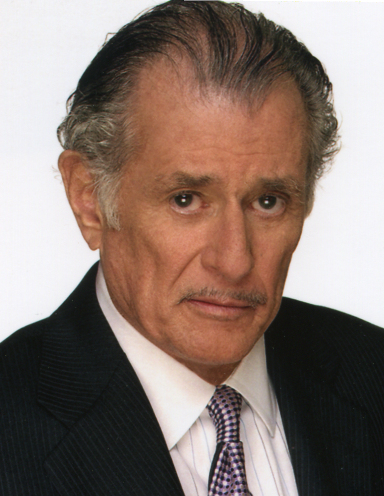

I worked with Frank Deford for several years at Sports Illustrated, and if you were to ask me to name his favorite sport, I’d have to say basketball, with tennis a close second. At least those were the two beats he covered before he was allowed to pretty much write about anything he damned well pleased, beginning in the late 1970s.

In the wake of his death last month at 78, various eulogists tried to name his most memorable pieces. Every list included at least a couple of basketball stories, most notably his insightful profiles of Bobby Knight and Bill Russell. His first piece for the magazine took him back to Princeton, his alma mater, where he introduced the nation to a young sophomore basketball player named Bill Bradley.

Since he came to SI right out of Princeton, Deford was known as “The Kid” during his early years at the magazine. He was so precocious that managing editor Andre Laguerre let him hang around with his Scotch-swilling, cigar-puffing entourage after hours. Frank took the inevitable teasing good-naturedly, and soaked up all the war stories the veterans could tell.

All of us wanted to be just like Frank, who would have been easy to hate had he not been such a decent guy. He was 6-4, with thick, wavy hair and a dimpled smile that made his a hit with the ladies, including the SI swimsuit models. He was married to a former fashion model, he was suave and sophisticated, and, mostly, he could write like an absolute dream.

He admired the wonderful prose of Red Smith, the legendary syndicated columnist based in New York, and it showed in the way he mixed humor with keen observation and a bit of cynical detachment. He wasn’t a stylist, in the matter of a Dan Jenkins or Jim Murray, but he was the best at getting his subjects to trust him enough to reveal their inner selves.

His detractors sometimes called him Defreud because of the way he got inside his subjects’ heads. But his profiles always were as honest as they were insightful. I knew Knight fairly well, but when I read Frank’s piece, my first reaction was, “Yes! He got him. Why didn’t I ever see that?”

That wasn’t Knight’s first reaction, however. He tracked me down in New Orleans, where I was covering a Super Bowl, and berated me for giving Frank an A-plus recommendation when Knight called to ask me if he should let Frank do the story. But I seem to recall that he calmed down somewhat when I pointed out that much as he might feel he exposed at that moment, it was a positive story that might lead some of his detractors to give him the benefit of the doubt.

Frank had a wonderfully curious mind, and, at that time, SI had both the leadership and the money to indulge his whims.

So Frank toured with the Harlem Globetrotters, even scoring eight points in the one game he suited up against them. He wrote about Victor, the wrestling bear, and the Roller Derby. One of his best pieces was about a tough-as-nails football coach who worked in the boondocks. And he loved the characters he discovered in the old American Basketball Association, which shook up the basketball establishment before being gobbled up by the NBA in 1976.

Much as I hated to admit it, I never caught many of Frank’s commentaries on National Public Radio or his interviews on “Real Sports With Bryant Gumbel.” It wasn’t that he wasn’t good at those things. To the contrary, he was excellent and built a huge following of listeners and viewers. It was just that, to me, Frank was first and foremost a writer who could read and explain people better than anyone ever has.

My most intimate memory of Frank goes back to the winter of 1971-72, when our wives were pregnant at the same time. Whenever we were off the road and crossed paths in the office, we’d spend a few minutes comparing notes, as young expectant fathers sometimes do.

Both our wives had daughters. Frank and Carol named theirs Alexandra, Alice and I named ours Amy. Shortly after that, I decided to move back to Kentucky so we could raise Amy around family. So it was awhile before I got the news that Alexandra had been born with cystic fibrosis, a disease that took her from Carol and Frank when she was eight.

Frank wrote a book titled, “Alex: The Story of a Child.” If you have never read it, I urge you to do so. He told his daughter’s story with love and humor, never getting maudlin. It was, perhaps, the best use that Frank ever made of his gifts.

As fate would have it, my friend Pee Wee Reese, captain of the Brooklyn Dodgers’ “Boys of Summer” teams, was involved with cystic fibrosis in Louisville. He recruited me to help him, and that gave me the excuse to bring Frank to Louisville for a fund-raiser. I can’t remember how much we raised, but I do recall that Frank charmed the crowd and got on famously with Pee Wee.

Of all the athletes Frank wrote about, I don’t think he was ever as close to a basketball player as he was to tennis star Arthur Ashe. They were kindred spirits, both intelligent, sensitive, and keenly interested in social justice. Sadly, Ashe died in 1993, at age 50, from AIDs, which he received from a contaminated transfusion while undergoing heart surgery.

I don’t recall anything special that Frank wrote about Ashe. However, his piece about the relationship between Jimmy Connors and his mother is one of his classics. Frank never was interested in easy subjects. The more complex they were, the more he was intrigued.

I’m not sure what the basketball writer in Frank would have said or written about Golden State’s tour de force in this year’s NBA playoffs. But maybe he gave us a hint when he defended the UConn women’s dynasty after the 2016 season:

“…sports fans have allegiances to their teams so that when somebody else’s team dominates, we get annoyed. By golly, it’s just not fair. Give somebody else a chance,” he said to his NPR audience. But then he ended his commentary with this: “Majesty is a thing of beauty to behold whatever the particular enterprise.”

Yes, indeed. Even if the enterprise is writing about basketball.

Billy Reed is a member of the U.S. Basketball Writers Hall of Fame, the Kentucky Journalism Hall of Fame, the Kentucky Athletic Hall of Fame and the Transylvania University Hall of Fame. He has been named Kentucky Sports Writer of the Year eight times and has won the Eclipse Award twice. Reed has written about a multitude of sports events for over four decades, but he is perhaps one of media’s most knowledgeable writers on the Kentucky Derby