“Is there a way to go back?” was the first question posed by a member of the audience after a recent one-time screening at Paducah’s Maiden Alley Cinema of “Look & See: A Portrait of Wendell Berry.” The provocative documentary featuring the renowned Kentucky writer, poet, teacher, farmer, and outspoken citizen of a lost landscape, begins with Berry’s lyrical narration of lines from his poem, “A Timbered Choir.”

“I saw the last known landscape destroyed for the sake of the objective, the soil bludgeoned, the rock blasted…”

Accompanying those lines is an aerial view of green treetops that glides into a devastating scene of mountaintop removal. The dreadful metamorphosis coincides with another stark line from Berry’s poem: “Those who wanted to go home would never get there now.”

“Look & See” takes viewers through each season with sounds and images that tell stories about the land, the people who have worked the land over generations, and the “unsettling of America” when farming was transformed from art to industry.

A clip from a 1972 press conference with Earl Butz, then Secretary of Agriculture, captures a turning point as Butz regales the use of technology and chemistry to enhance profits. The consolidation of U.S. farms followed, with the emphasis on farming as an industry, not a way of life.

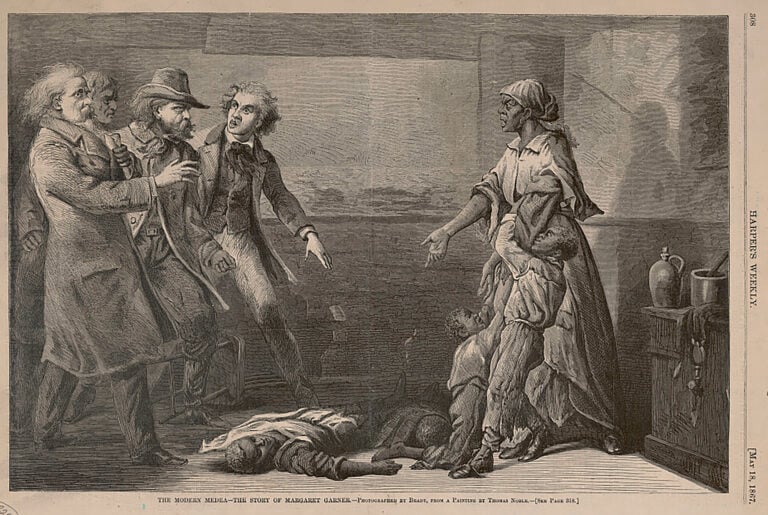

Quantity over value was the equation. The result, according to Wendell Berry and other Kentucky farmers featured in the film, makes slaves of people in subtle ways. The drive toward mechanization, the grinding effort to trim thin margins, the difficulties associated with hiring seasonal workers, all add up to a decline of rural America.

Wendell Berry sees this trend as a sign of lack of imagination, leading to a false economy. “It works against nature,” he declares.

“Look & See” leaves viewers with a vision of years far into the future, as hope hovers on the horizon with the local food movement and organic growing methods. The film’s epilogue challenges audiences “to stand like slow growing trees,/ on a ruined place, renewing, enriching it…”

The promise is that, long after we are gone, the river will run clear. Veins of forgotten springs will open. The film ends with a vision described in Berry’s poem “Work Song Part II.”

“Families will be singing in the fields…/ This is no paradisal dream./ Its hardship is its reality.”

Still on my mind at the end of “Look & See” is the question posed at the beginning of this column: “Is there a way to go back?”

The chances seem slim to none, unless some natural or man-made catastrophe forces a 180-degree turn. Yes, there is nascent movement toward food sovereignty, which is defined as the right to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through sustainable means. The concept is timely and relevant, but the reality of food sovereignty means retreating from conveniences we have depended on for generations.

“Look & See” is a film beautifully made and thoughtfully constructed, leaving audiences with much to ponder. One image that stays with me is that of an old clothesline outside a farm house. The clothes pins are still there, wanting use, but likely worn-out from years of disuse and careless exposure to the elements.

More about the film, and information about arranging screenings is available at lookandseefilm.com.

Constance Alexander is a columnist, award-winning poet and playwright, and President of INTEXCommunications in Murray, Ky. She can be reached at Calexander9@murraystate.edu. Or visit her website.