By Steve Flairty

NKyTribune Columnist

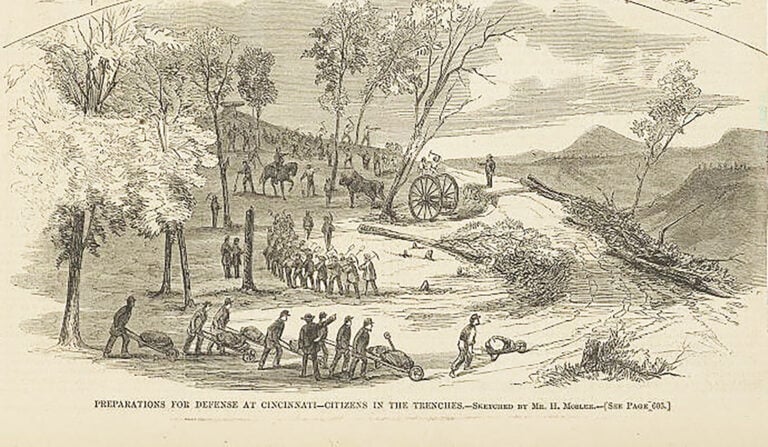

It was 1937, the year of the Great Flood that imposed itself on the Ohio River and its banks, causing immeasurable destruction. Near Ross, Kentucky, Bellevue-born Harlan Hubbard worked methodically by the river in front of his art studio, carefully gathering an abundance of driftwood gifted him by nature’s proceedings. Musing for a moment, he paused to scribble into his notebook, “Into my bare front yard, the last place one would expect to find firewood, the river brought enough to keep me warm all winter.”

Adding to those words later, his worldview might well have been summarized by another Hubbard offering: “What we need is at hand.”

And simply, what was at hand for Hubbard lurked later at his and his spouse’s home at Payne Hollow, in Trimble County, on the good earth with the whole of nature that adorns it, where one takes a long break from a manufactured world of conventionality and sets one’s own rules.

Hubbard, many say, reigned there as “Kentucky’s Thoreau.” With that, his story needed to be told with (forgive me) “thoreau-ness.”

Jessica Whitehead, in Driftwood: The Life of Harlan Hubbard, perhaps goes further than all before in uncovering the writer, artist, and naturalist’s family background, his education, and his significant relationships, especially those with his mother, Rose, and his soulmate, wife Anna, who added polish to Harlan’s simple and otherworldly lifestyle, offering the perfect partner for it.

In 306 pages of well-researched material, punctuated by her close reading of Hubbard’s voluminous journal writings, the author offers numerous photos and a generous sampling of Hubbard’s paintings. Whitehead presents her subject with passion and care, perhaps hoping, like Hubbard aspired, to create in her readers a “flood in my soul, to carry off all the old drift and the flimsy habits that have extended down to the water’s edge.”

Whitehead, who first learned of Hubbard while a student at Hanover College, works as a writer and curator of collections at the Kentucky Derby Museum and has co-authored and contributed to two other books. She has most to say and admire about the subject of Driftwood, however, emphasizing that Hubbard was truly different, and that his legacy demonstrates one who truly followed his heart.

Whitehead notes that his philosophical ethos, “alongside the deep joy and satisfaction of a life well-lived, there existed significant sacrifice. Harlan’s worldview cultivated in opposition to the greed, exceptionalism, and exploitation he saw in most examples of modern American culture, (and) required the deliberate, often lonely, and always laborious work of challenging modes of convention.” For that, she explained, he was “never traditionally successful within the confines of capitalistic society.”

He COULD have been successful in that way, as he possessed amazing talent.

Hubbard, to his credit, spent much time attending to the needs of his aging mother, taking over for his older brothers who supported her earlier. Much of his striving personality came from Rose, though the two reached for different things—hers being more toward success in the eyes of the community, his self-realization.

And in his emerging relationship with future wife, Anna, there would be some equilibrium Harlan would seek to counter his busy responsibilities. Whitehead explained it this way: “While Harlan was trying to juggle all of these pieces of his life—his mother’s care, keeping up with the rising expenses by doing construction work, keeping up with the house and the garden, maintaining correspondence with his mother’s doctors, and his painting—he was also trying to work out where things were going with Anna.”

Harlan’s relationship with Anna became a positive distraction from his burdens, and the two enjoyed playing music together, dating, and they were “growing closer and spending extended periods of time in each other’s company.” They went on short canoeing and camping trips together, she noted, “when Harlan managed to find a nurse Rose would tolerate.”

It was a time for Harlan “to see how adaptable Anna was to whatever circumstance she faced,” wrote Whitehead. The testing period demonstrated accurately that Anna was up for both hardship and deep joy in her long partnering with Harlan.

In April 1943, the two married in an old courthouse in Maysville in a simple ceremony. It was a windy and chilly day, but after the ceremony, they took a walk about four miles east along a railroad track to a tiny community called Springdale, along the Ohio River. They felt, Whitehead said, “the mutual warmth of shared company spent in a beloved landscape.” It was a fitting prologue to what came in their over four-decade marriage.

Rose died on November 16, 1943. Late in life, Harlan commented: “The first forty-three years of my life were spent under my mother’s domination and the next forty-three years of my life were spent under my wife’s, Anna.” The difference was that he chose Anna for himself.

In actuality, the book’s narrative of their marriage demonstrated a collaborative effort, and it had to be. They took long hikes together, sometimes walking twenty miles a day in bad weather. After building a shantyboat in 1944, they began their “drift” in 1946 downriver to New Orleans and the Bayous, arriving in 1951. There, they sold the boat and left by car to the West and came back to Kentucky in May of 1952. Harlan would chronicle the journey in a well-received book published in 1952, called Shantyboat: A River Way of Life.

But they were just getting started. Life at Payne Hollow was not easy, but it was satisfying for the couple’s tastes. They basically lived off the land (but also ate meat), had no electricity, and used cistern water. Their house was made of wood and stone, and in time, a shed, workshop, and an art studio, where Harlan created a prolific number of art pieces, some of which were sold to the outside world. Anna had her Steinway piano moved to their home, a very challenging task to get it there, and the two played—and made—music together. Their art also consisted of reading classical books to each other and sometimes acting out scenes.

Harlan Hubbard never drifted far from his dreams, and he created his own kind of thoreau-ness.

Books authored by Harlan or about him include the aforementioned Shantyboat; Payne Hollow: Life on the Fringe of Society; Shantyboat on the Bayous; and Shantyboat Journal. Noted author Wendell Berry, a friend of Harlan, shared similar views and wrote Harlan Hubbard: Life and Work.

Former Kentucky Poet Laureate Richard Taylor said of Whitehead and Driftwood, “In a feat of research and revelation that avoids hagiography, Whitehead has made this icon fully human, examining the mythos of a legendary Kentuckian to reveal the essential Hubbard, a man we would have to invent if he had not existed.”

Harlan died in 1988, two years after Anna.

Visit driftwoodharlanhubbard.com for plenty more information on the book, including exhibits and events currently in progress. An effort by citizens, including Whitehead, to preserve Payne Hollow and inform the legacy of the Hubbard couple was formed in 2022. Visit www.paynehollowontheohio.org for details.

Yet another outstanding column from Steve! I loved it!