By Raymond G. Hebert, PhD

Special to NKyTribune

The Encyclopedia of Northern Kentucky relates that Bobby Mackey’s Music World had a storied building on 44 Licking Pike in Wilder that “was preceded by one constructed about 1850, which served as a slaughterhouse and meatpacking plant in what was called Finchtown.” The entry then details several nineteenth-century tales that eventually played into the building’s reputation as one of Northern Kentucky’s haunted sites: a place that collected animal blood (as a slaughterhouse), and where occult groups used what became abandoned buildings for its rituals in the later 1800s. In 1896, the infamous murder of Pearl Bryan occurred in Campbell County, her head having been decapitated. Rumors abounded as to the “whereabouts of Bryan’s head.” One bit of speculation, according to several sources, was that “the head was used in an occult ritual and disposed of in the well of the old slaughterhouse” (Robin Caraway, “Bobby Mackey’s Music World,” in Paul A. Tenkotte and James C. Claypool, The Encyclopedia of Northern Kentucky; Robin Caraway, “Wilder Nightclub Site Has Storied Past” Cincinnati Post, July 17, 2006, p. 14

The building was abandoned for many years, was torn down, and was eventually rebuilt as a “roadhouse,” as a speakeasy gambling establishment in the 1920s, and as a popular nightclub called “The Primrose” in the 1930s. Taken over by the Cleveland Syndicate who pressured the previous owners, it was called “The Latin Quarter,” soon becoming “one of the mob’s hot spots in Northern Kentucky.” With many questionable and illegal activities, and related stories in its wake, the Latin Quarter continued to be successful, especially symbolically, until the 1960s. As efforts were made throughout the county against organized crime, the name was changed to “The Hard Rock Café.” It was noted, though, that “after several fatal shootings on the premises, the club was closed by the police in 1977” (Caraway, Encyclopedia of Northern Kentucky).

In 1978 a young well-known local country singer named Bobby Mackey purchased the building and renovated it so he could have a music venue and country-western bar. Many sources highlight his mechanical bucking bull, supposedly the most challenging in Northern Kentucky, and his stage for live musical performances, but they also note the simultaneous claim that the club’s site was “haunted” or “spooked.” These claims attracted national attention, with segments about the club appearing over time on television shows such as Hard Copy, Geraldo, Sightings, Jerry Springer, and A Current Affair, as well as on the Lifetime Channel.

Looking back on its success over the years, there seems to be no doubt that some of it can be linked to the reputation it developed as “the Most Haunted Nightclub in America.” In one famous example, the television show Paranormal Lockdown arrived in 2018 with two paranormal investigators “confining themselves inside the nightclub for 72 hours, while they searched for any evidence of paranormal activity.” The episode aired on December 11, 2018. One of their discoveries was what they called a potential “Portal to Hell” (Sarah Horne, “40 Years of Bobby Mackey’s – Come for the Ghosts, Stay for the Music,” Cincinnati Enquirer, January 10, 2019, p. B4). Interestingly, while Mackey had said repeatedly that, for him, “it was always about the music” amidst the concerns that the paranormal stories would harm the reputation of the club, he soon realized, that instead, it could likely bring more interested people to the club and, in his words, they might have come for the ghosts but stayed for the music. Horne opined, “Mackey still enjoys writing music (in 2019) and he continues to record songs” (Horne).

The syndicated series Hard Copy also came to Bobby Mackey’s to “report on the strange occurrences at the club that have led some to believe it’s haunted.” That was later reported to have been a turning point for the club as a haunted venue (“Hard Copy Seeks Ghosts at Bobby Mackey’s,” Cincinnati Post, June 6, 1991, p. 22). One month later, David Wecker, a popular Cincinnati Post columnist for the newspaper’s “Living” section, echoed the topic of the validity (or not) of the establishment’s “demon story.” Wecker mentioned Doug Hensley’s book, Terror at Music World, stating that “Bobby Mackey had no idea that the Latin Quarter in Wilder, KY was demon possessed when he turned it into a country music emporium in 1978.” Hensley “buttresses his story with the ‘sworn affidavits’ of 25 individuals who have had other-worldly experiences at Mackey’s Music World.” Wecker concluded that there would still be skeptics who would continue to believe that “Bobby Mackey cooked up the whole story to get people to come to his nightclub” (David Wecker, “Bobby Mackey Demon Story: Truth or Bull,” Cincinnati Post, July 9, 1991, p. 11). From that time on though, the legend was established and has persisted to the present day.

Two years later, after a brief foray on the talk-show circuit about his haunted venue, Bobby Mackey hoped to expand by constructing a new, larger club but “was crippled by a 200-foot-long crack in the ground … right up through where the new building was supposed to be.” The alternative was to build in phases on the same site but “he couldn’t close for construction (and) the building that houses the club is 75 to 100 years old.” The article also alluded to conversations with the city about alternatives but with no resolution (Brenda J. Breaux, “Crack in the Earth Breaking This Ol’ Country Boy’s Heart,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 16, 1993, p. 16).

Not to be stymied, Mackey continued to write and play his music, and, in 1994, he returned to Nashville with an untitled album but a potential “hit song” called “What’s He Got That I Ain’t Got.” Cliff Radel, in his column, praised Mackey for his 16 years of persistence as “a throwback to country before it got hot (and that) his club was also a throwback … with the ambiance of a well-used honky-tonk … [and] not a club where you just come in, sit down, and look at the stage” (Cliff Radel, “Country Boy” in “Where to Go Club Crawling,” Cincinnati Enquirer, February 11, 1994, p. 83).

A fire at Bobby Mackey’s in 1997 caused $3,000 in damage and it set the club back briefly, but it continued to plug along. It was suspected arson started by an unhappy customer who had been ejected and said, upon leaving, “I’ll never come back here, and you’ll be sorry” (Frank Main, “Fire at Bobby Mackey’s Proved,” Cincinnati Post, March 3, 1997, p.7).

Later articles echoed the same theme of how the nightspot “a honky-tonk in the classic tradition… had weathered country music’s booms and busts from the ‘Urban Cowboy’ craze of the early ‘80s to Garth Brooks in the ‘90s to today’s country pop.” In Mackey’s words, “I’ve been through all the styles and stayed the same” (Larry Nager, “Haunted Honky-Tonk,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 24, 2001, p. 104). Four days later, the Enquirer again included Bobby Mackey’s as an example of a site having “ghosts,” noting that, on its website, it describes itself as “the most haunted bar in the nation.” A psychic is even quoted as having said that “Bobby Mackey’s was one of the scariest ghost-busting jobs I’ve ever been on” (“Ghosts: Tristate’s Own Apparitions,” Cincinnati Enquirer, October 28, 2001, p. 26).

Happily, for Mackey, the focus shifted to the quality and lasting power of the music. One article opened by saying: “First-time visitors to Bobby Mackey’s Music World often come for El Toro, the mechanical bull, or perhaps the rumors of paranormal activity, but they quickly learn the music is the main attraction” (Stephanie Romine, “Old Haunt for Country Fans,” Cincinnati Enquirer, January 19, 2007, p. 45).

In 2008 the emphasis shifted to the 30 th anniversary of Bobby Mackey’s and a historical look at how the building went from a slaughterhouse in the 1880s to a casino in the 1930s, and, into the 21st Century was now “the longest-running country venue in the Cincinnati area … set apart even more because people believe it’s haunted.” Again, Mackey denied believing in ghosts, adding this time: “When I say I don’t believe in it, I think they’re a little disappointed. They want to hear a ghost story” (Gil Kaufman, “Bobby Mackey’s: 30 Years of Country and Creep Show,” Cincinnati Enquirer, September 5, 2008, p.47).

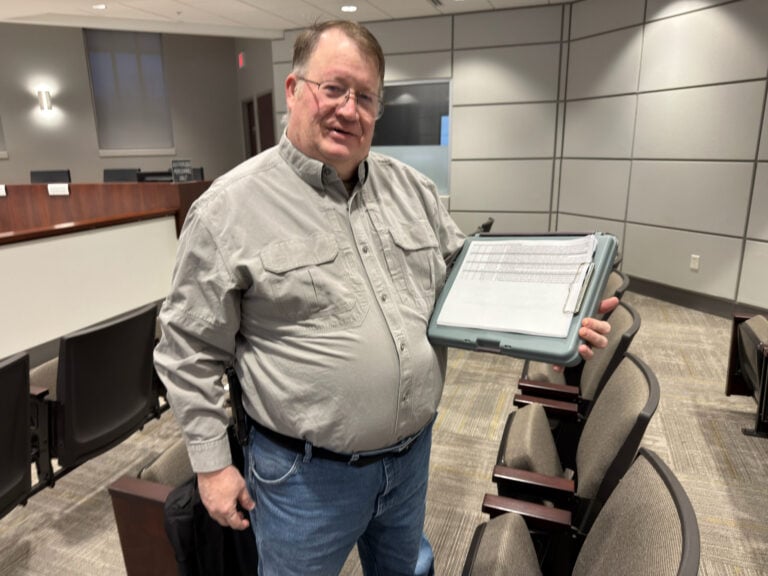

Bobby Mackey was frequently involved and supportive of programs and projects that benefitted the community. In 2011, for example, he hosted the kickoff for the Northern Kentucky Youth Foundation’s capital campaign. In his words, “I am so proud to be a part of this organization … I’ll do whatever I can to help them out.” He was quite enthusiastic about his support for their mission of “helping youth ages 12 to 18 reach their potential through social, educational and recreational activities” (Deborah Kohl Kremer, “Musician Helps Youth Foundation,” Cincinnati Enquirer, January 1, 2011, p. 26).

In 2014 Travel Channel show Ghost Adventures: Aftershocks, hosted by Zak Bagans and other paranormal investigators, included significant interview time with Bobby Mackey that Bagans described as “intense” (“Bobby Mackey Will be on New Travel Channel Show,” Cincinnati Enquirer, April 5, 2014, p. A24). Bobby Mackey’s began “incorporating a haunted tour as part of the business” (“Mackey’s, Cincinnati Enquirer, January 10, 2019, p. A2).

The ongoing saga of the ghosts and, more importantly, of the success of Bobby Mackey’s Musical World as a country western music venue for 46 years reached a turning point with the decision and announcement by Mackey that he was looking for a “fresh start.” In her article about this new twist, Haadiza Ogwude opens by saying that “the bar dubbed America’s most haunted nightclub is being demolished” by the end of 2024. Her article repeats key items of the history and controversies but ends significantly with Mackey’s reflections. The first one is his desire to “make what he has better” in a “suitable venue for his band and fans.” He talked of “still having some career life left (at 75)” (Haadiza Ogwude, “Demolition of Haunted Nightclub Is ‘Going to be Bittersweet,’” Cincinnati Enquirer, March 24, 2024, p. B1).

After demolition in 2024, Bobby Mackey’s temporarily continued operations at the former location of Mugbee’s Biker Bar and Restaurant on 8405 US Highway 42 in Boone County. Hopes are that a new bar can be built on the site of the demolished original building, ideally by 2026.

On October 26, 2024, Bobby Mackey was inducted into the Kentucky Music Hall of Fame. It is a fitting tribute to a man whose music has entertained thousands over a decades-long career.

Dr. Raymond G. Hebert is Professor of History and Executive Director of the William T. Robinson III Institute for Religious Liberty at Thomas More University. He is the leading author of Thomas More University at 100: Purpose, People, and Pathways to Student Success (2023). The book can be purchased by contacting the Thomas More University Bookstore at 859-344-3335. Dr. Hebert can be contacted at hebertr@thomasmore.edu

Paul A. Tenkotte, PhD is Editor of the “Our Rich History” weekly series and Professor of History at Northern Kentucky University (NKU). He can be contacted at tenkottep@nku.edu. Tenkotte also serves as Director of the ORVILLE Project (Ohio River Valley Innovation Library and Learning Engagement).