We’re celebrating ten years of Our Rich History. You can browse and read any of the past columns, from the present all the way back to our start on May 6, 2015, at our newly updated database: nkytribune.com/our-rich-history

By Paul A. Tenkotte, PhD

Special to NKyTribune

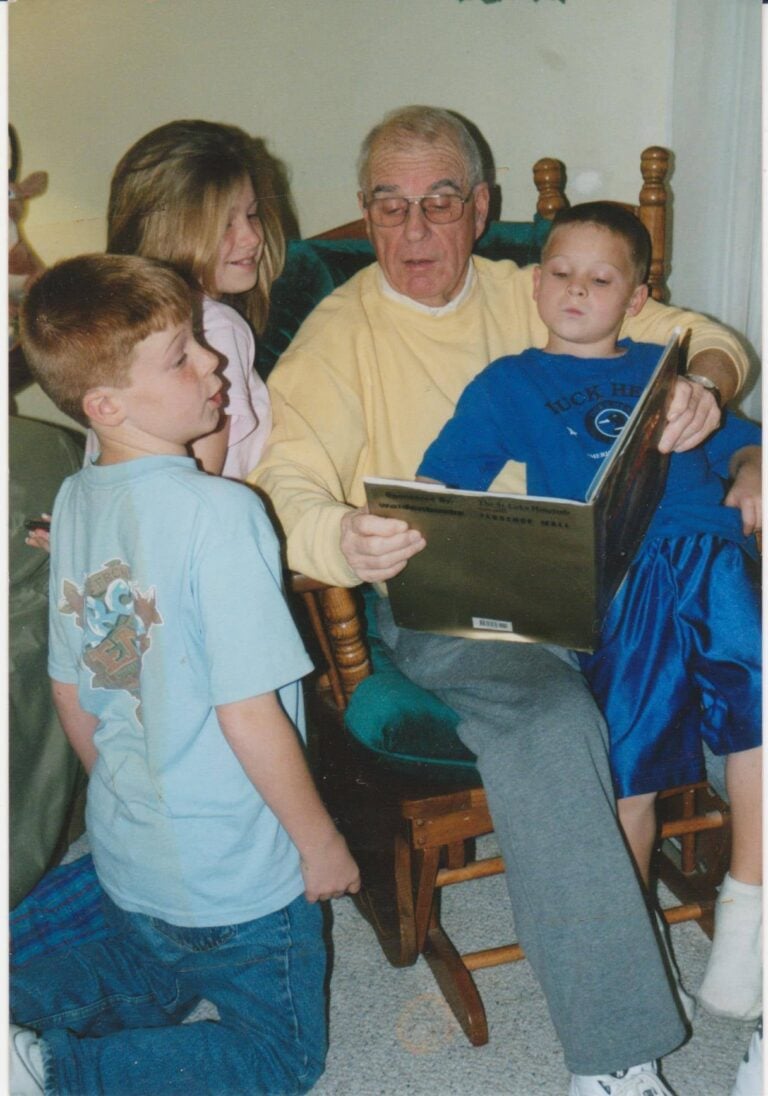

Several weeks ago, a longtime friend, Pamela Mullins, shared with me a Thanksgiving 1997 interview that she had videotaped of her great uncle, John Franklin Pennington, and had posted on YouTube.

I watched the entire 56 minutes in one sitting and found it thoroughly riveting. So often, the story of Covington’s Black community has been forgotten. Through the eyes of John Franklin Pennington, it comes alive, as well as that of segregated postwar America.

John Franklin Pennington was born on October 12, 1918, in Maywood, Kentucky, just south of Stanford in Lincoln County. His parents, Claiborne Allen “Bud” (1861–1956) and Margaret Hanna Higgins (1871–1946), owned an 80-acre farm. John was the youngest of 12 children (7 boys and 5 girls). His father raised produce to feed his large family, as well as tobacco to sell. As the children grew older, they moved away. John was the last to leave the family farm after graduating from a segregated high school in Stanford in 1939 (ancestry.com).

John’s brother-in-law, MacArthur Hayes, worked at a steel mill in Covington, Kentucky, and helped him to secure a job there in 1939 “chipping steel.” John’s White boss befriended him, placing him in charge of what John called “an all-Black gang” of workers when the boss was away. Later, when an inspector position became available at the plant, John applied and much to the surprise of his brother-in-law who scoffed at his application, he got it. There were only two other Black inspectors at the mill, both of whom had been employees there much longer. Stated John, “If you don’t ask for something, you’re never going to get it.”

In an interesting turn of events, John’s Black workers were jealous of his promotion, so began to slack off in their work. As the tonnage numbers of his employees began to drop under his supervision, John worried that he would lose his job. Surprisingly, his boss understood the jealousy that was occurring and assigned him as inspector of an all-White gang, whom John stated, respected him.

John Pennington worked at the Covington steel mill until June 25, 1943, when he joined the US Army during World War II. He would spend more than 2.5 years in the military, six months in statewide training and two years in Italy. A corporal for the 189th Engineers Aviation Battalion, he earned an honorable discharge in February 1946 (ancestry.com).

The US armed forces were segregated at the time of World War II. John took his military training in St. Louis, Missouri, where he earned the respect of his commander, who placed him in charge of leading 17 fellow Black soldiers to Eglin Field of the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) in Florida’s panhandle, three miles south of Valparaiso. The trip there, through the segregated South, proved especially disheartening and dehumanizing.

In Alabama, railroad officials forced them to ride in a segregated car. Upon arrival in Florida, not far from Eglin, they awaited an army truck to ride them to the base. Tired and hungry, the soldiers went to a local sandwich shop. Realizing that they would not be able to dine in the segregated restaurant, they did what Blacks in segregated America always deferred to in such instances—they assumed that they could at very least order take-out. However, this restaurant refused even that, and when John entered the sandwich shop hoping to convince the cook that they were army soldiers protecting him and other Americans, they were sternly told to leave.

In an amusing story, when John and his Black convoy were leaving Eglin for Virginia, they passed through the same small town where the segregated sandwich shop had refused to serve them carryout. The townspeople met them with racist jeers of “goodbye ni**ers!” In a show of solidarity, the Black soldiers rained their rifles into the air, succeeding in scaring but not harming the bigots.

In Virginia, John boarded one of the liberty ships in the center of a large convoy headed for Italy. At one point, another ship came close to hitting their ship accidentally, at which point their ship’s commanding officer literally suffered a heart attack. They soon discovered the reason for his great distress—their ship was filled with dynamite, a fact the enlisted soldiers had not realized.

Arriving in Italy, where the American troops remained racially segregated, they nevertheless experienced the openness of the Italian people. Italian clubs and restaurants were integrated. On one occasion, John was sitting alone in a restaurant when tears began to fill his eyes. An Italian lady asked him what was wrong, and he replied in Italian “nothing.” In truth, however, he was saddened by being ill-treated in America because of his race, the exact opposite of Italy. Not surprisingly, some Black soldiers stayed in Italy after the war, rather than return to the segregation of their homeland.

In Italy, John and other Black soldiers were charged with building landing strips for American planes. Later, earning the respect of his commanding officer, he became the entrusted soldier to secure supplies for his unit at headquarters in Naples, two hundred miles away.

When World War II ended in Europe, John and others were scheduled to be shipped to the Pacific Theater. Before they could get underway, however, the war ended. Although his company commander offered him a promotion to warrant officer if he remained in the service, John refused, knowing that his mother was ill and aging in Kentucky. She died in 1946, shortly after his return to the US.

Eventually, John joined army friends in Lansing, Michigan, where he secured a job and met and married his wife Ruby Price (1922–2015). He took flying lessons and earned his pilot’s license, a rare feat for Blacks during that time period. He worked his way up from a maintenance man in a used car lot to car sales. For 17 years, he was employed by Buick dealerships, and then in sales for a Cadillac dealership in Detroit (1970–1985).

While working as a salesman for Carson Buick in Detroit, John’s boss sent him to the General Motors Building in Detroit to represent the dealer at the company’s showcase. There, John discovered that he was the first Black salesman to market Buicks in the company’s display room. He even earned a story in a Detroit newspaper.

In 1985 Pennington, or “Penny” as he was called by his friends, retired with Ruby to metropolitan Albuquerque, New Mexico. There, his wife died in 2015. At age 97, John Franklin Pennington passed away on February 6, 2017, after relocating to Kentucky. Ninth Street Baptist Church in Covington held a funeral service, as did his church in New Mexico, where he was buried.

The story of John Franklin Pennington is one of hope, patriotism courage and success during a time when racism and segregation slammed many doors in the faces of Black Americans. It is an inspiration to all—no matter what your background or circumstances are in life—that love and hope reign supreme against hate and darkness.

Paul A. Tenkotte, PhD is Editor of the “Our Rich History” weekly series and Professor of History at Northern Kentucky University (NKU). To browse ten years of past columns, see: nkytribune.com/our-rich-history. Tenkotte also serves as Director of the ORVILLE Project (Ohio River Valley Innovation Library and Learning Engagement). He can be contacted at tenkottep@nku.edu.