By Howard Whiteman

Murray State University

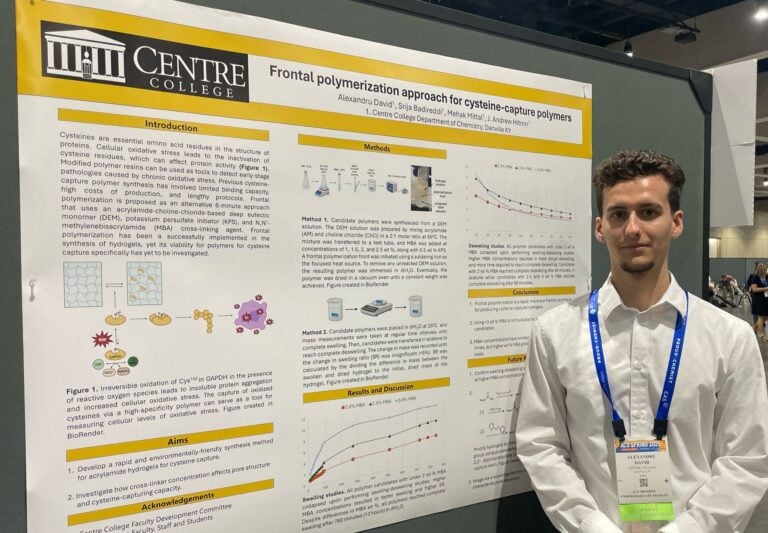

Last week my research students and I were carefully searching a beaver pond for Boreal Toads that we helped restore last year. A biologist had found some toads a few weeks back and we were eager to see them for ourselves, and confirm with our own eyes that they had indeed survived the harsh Colorado winter.

Eventually, we found one. And then another, and then a dozen. I am sure we could have found many more had we spent the time, but once we had admired them and taken a few photos, we backed out of the site. They are the beginning of a restoration that many people have worked years to make a reality, and here it was, happening before our eyes.

Toad restoration may not be as sexy and is certainly not as controversial as the reintroduction of wolves, but it is important nonetheless. Boreal Toads and other amphibians have been decimated by a fungal disease called chytrid. It affects their skin, and because the skin is such an important organ for amphibians, it negatively affects their health and often leads to death. Restoration is one of the few things we can do to try to help conserve Boreal Toads and other amphibian species affected by chytrid.

If a toad could speak, I am sure it would scream for a vaccine. Amphibians are not alone: many other species have been negatively affected by fungal diseases, often inadvertently spread by humans.

Dr. Suess’ Lorax proclaimed “We speak for the trees.” In today’s world, he might have said “We speak for the vaccines,” because many species besides humans are in dire straits because of disease. Scientists would love to have vaccines to make these problems go away, and perhaps if we put more effort and funding toward them, we would. Having vaccines is a game changer, and I am sure that if the diseased plants and animals of the world could, they would line up for them. This is particularly true of amphibians like Boreal Toads.

Amphibians are among the most important warning signs we have, and their decline suggests that we need to start paying more attention to fungal disease. Because they are so sensitive to environmental change, they are like a canary in a coal mine, and we can use them as a measure of the health of our planet. In this case, however, we can’t just run out of the mine to get fresh air. We have to find another way.

But here is the rub for toads and humans alike: we do not have a viable vaccine for any fungal disease.

I was reminded of this unnerving fact watching The Last of Us, an HBO series about post-apocalyptic survival. It’s not that I am concerned about the idea of fungal-controlled zombies, which is a wonderfully hideous but entertaining part of the plot, and also, to a small degree, completely plausible. Fungi really do control other species the way it is described in the show; a lot of parasites do.

The real problem is the first few minutes of the first episode, which are more accurate than I would like. In the clip, a scientist reveals that we don’t need to be concerned so much about viruses (like COVID) because we know how to make vaccines for them. What we do not know is how to create a vaccine for a fungus. As a biologist, this sent chills down my spine, because, as amphibians and other organisms have shown us, species have been dying off on our planet due to fungus for over a century, and we seem to be just watching it happen without making much progress on stopping it.

In reality, we are developing vaccines for fungus, but we are very much way behind, in part because fungal cells are not all that different from our own. As difficult as it is to create vaccines for viruses, it turns out it is a lot easier than creating one for a fungus.

It is estimated that a million people die each year because of fungal diseases. That is a lot less than many other diseases, but a second piece of that Last of Us clip turned out also to be true.

As the planet warms due to climate change, fungal diseases have become more prevalent, and they have the potential to adapt to infect mammals, including humans. For decades, amphibians have been showing us what very well might be coming our way. They may not be speaking, but they are telling us nonetheless.

History suggests that we can develop vaccines for fungal pathogens, because the science of vaccines stands on strong shoulders. Vaccine technology started in the 1600s, progressed in the late 1700s to produce the first smallpox vaccine, and has since led to the control or eradication of numerous diseases, including cholera, anthrax, tetanus, dipthera, and pertussis. If some of those diseases sound arcane and lost to history, they are. That is what an effective vaccine does.

Most recently, advances in molecular biology have allowed the development of hepatitis B, flu, and COVID vaccines. Vaccine development may also allow us to treat allergies, autoimmune diseases, addictions, and perhaps someday, fungus.

Like many other scientific discoveries, our ability to affect the spread and impact of disease is built upon hundreds of years of previous science. However, similar to previous diseases that affected humans, vaccines have to be widely deployed to stop the disease in its tracks. Every person with cold feet, or every person that listens to a misguided politician full of misinformation over scientists, is one more foothold for the disease to spread, and is one more opportunity for someone to get sick and die.

Now is the time to start thinking harder about building off of our previous success to combat fungal diseases, not because we are scared of being turned into zombies but rather because the species with whom we share the planet have been showing us that they are an eminent threat to human health.

Now is certainly not the time to jeopardize humans by cutting science funding and filling panels with vaccine skeptics. Adding vaccine skeptics to a previously scientific panel trying to make decisions about vaccine implementation, after all of the history we have with vaccine creation and implementation, is akin to an 18th century witch hunt. It’s not based in fact, and whether some politicians believe it or not, facts matter in the reality-based universe of disease transmission. If we continue down this path, we will all pay the price, and America will re-learn lessons that are centuries old, the hard way.

If they could, I am certain that the other organisms that share our planet, including the toads we are trying to conserve, would shake their collective heads at the idiocy of our self-proclaimed superior intelligence. There is nothing intelligent about ignoring science.

However, if we can take science seriously again, and apply this same science to fungal diseases, we could kill two birds with one stone. By learning how to vaccinate toads and other species against fungus, we would not only help restore their populations but also learn how to develop vaccines for humans as well.

Our fellow organisms are clearly telling us “We speak for vaccines.” The question is, will we listen?

Dr. Howard Whiteman is the Commonwealth Endowed Chair of Environmental Studies and professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at Murray State University.