By Steve Flairty

NKyTribune columnist

The first time I recall hearing much about Kentucky’s infamous Day Law was in 2007 when I interviewed Bettie L. Johnson for my Kentucky’s Everyday Heroes book series. Bettie, an acclaimed African American educator, Civil Rights advocate and nursing home director from Louisville, shared with me that she was not allowed admittance to the University of Louisville (U of L) in the 1940s because of the color of her skin.

Fortunately, Bettie found other colleges to attend, performed well, and gained much success. With great irony, she became a great benefactor of the later integrated U of L, and amazingly, had a campus dormitory named for her.

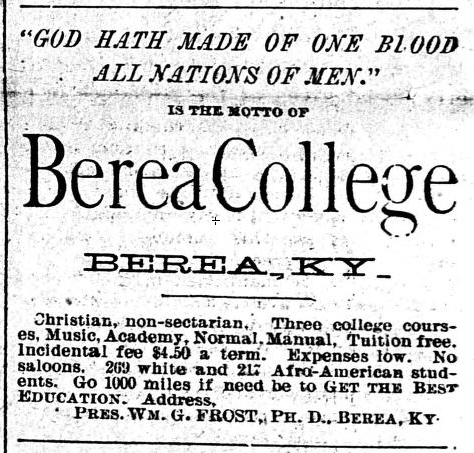

Before Bettie was born, a sad part of Kentucky’s history took place in 1904 at the passage of the Day Law, which happened the same year it was introduced in the Kentucky legislature by Representative Carl Day. Day had visited Berea College, at the time the only integrated college in Kentucky. While there, he saw and didn’t like the mixing of Whites and Blacks in the classrooms.

Angry, Day proposed the law which, according to the Kentucky African American Encyclopedia, made it “illegal for any college or school in the state to be integrated, or for any private institution to establish an integrated branch within 25 miles of the mother institution. The law was a manifestation of Kentucky’s continual de jure and de facto racial discrimination against African Americans in the late nineteenth century.”

I asked Emeritus Professor of Kentucky History at EKU, Dr. Thomas Appleton, if the Day Law reflected the wide wishes of Kentuckians at the time. “Scientific polling was still some 30 years in the future, so we have no hard data on what percentage of white Kentuckians favored the Day Law. My feeling is that once Carl Day introduced the bill, the legislation took on a life of its own,” said Appleton. “Most white legislators, I imagine, chose to go along with the passage out of fear that an opponent might use a nay vote against him in the election. I don’t think there was any popular groundswell of support for the legislation.”

The then president of Berea, William Goodell, opposed the Day Law, though he admitted that during his presidency, the ratio of the races sitting in classes had gone from 50-50 to about 7 to one. The Kentucky Court of Appeals ruled against Berea College and changing the Day Law. In a subsequent appeal, the Supreme Court agreed with the lower court ruling. Justice John Marshall Harlan, who I previously wrote about in this column, wrote a strong dissent against the Supreme Court decision.

Berea College had been integrated since 1866. After the Day Law passage and losing of the appeal cases, Berea College founded a new school for Blacks near Simpsonville, in Shelby County, named the Lincoln Institute (LI). About 444 acres were purchased, and one newspaper editor called LI the “new Berea” for Blacks. It was, however, different from Berea College. It presented itself as a private secondary boarding school for those who couldn’t receive an education in their home districts.

The Great Depression came in the 1930s, and the Lincoln Institute’s endowment, not surprisingly, was throttled. To help, the school partnered with the public Shelby County school system to educate black students, and the Kentucky Board of Education worked with the school to establish a student teacher-training center for what was then the Kentucky State College. In 1946, the state of Kentucky was deeded the Lincoln Institute property and Kentucky State College was chosen to direct it.

The Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 disallowed legally segregated schools. The school’s name was changed to the Lincoln School, but by 1970, it had closed because of criticisms of its management.

Today, the fully integrated Berea College is thriving, and in 2025, Washington Monthly named it #1 in the United States for its tuition value.

And when Bettie L. Johnson was kept out of her college of choice, along with many others like her, it turned out to be the colleges’ loss. Black History Month focuses on many such stories, and I hope you’ll look for them for your inspirational reading during this month.