By James D. Porter III

Special to NKyTribune

By August 1862, the United States was entrenched in the Civil War between the loyal Union states and rebelling Confederate states. Despite an early vote to secede by self-appointed revolutionaries, Kentucky remained faithful to the United States and by the end of the war an estimated 74,000 to 125,000 Kentuckians served as Union soldiers. Regardless, Kentucky officially declared neutrality in May 1861, prompting Confederate attacks in an attempt to take the state as their own (A. C. Quisenberry, “Kentucky Union Troops in the Civil War,” “Register of Kentucky State Historical Society,” vol. 18, no. 54, 1920, pp. 13-14).

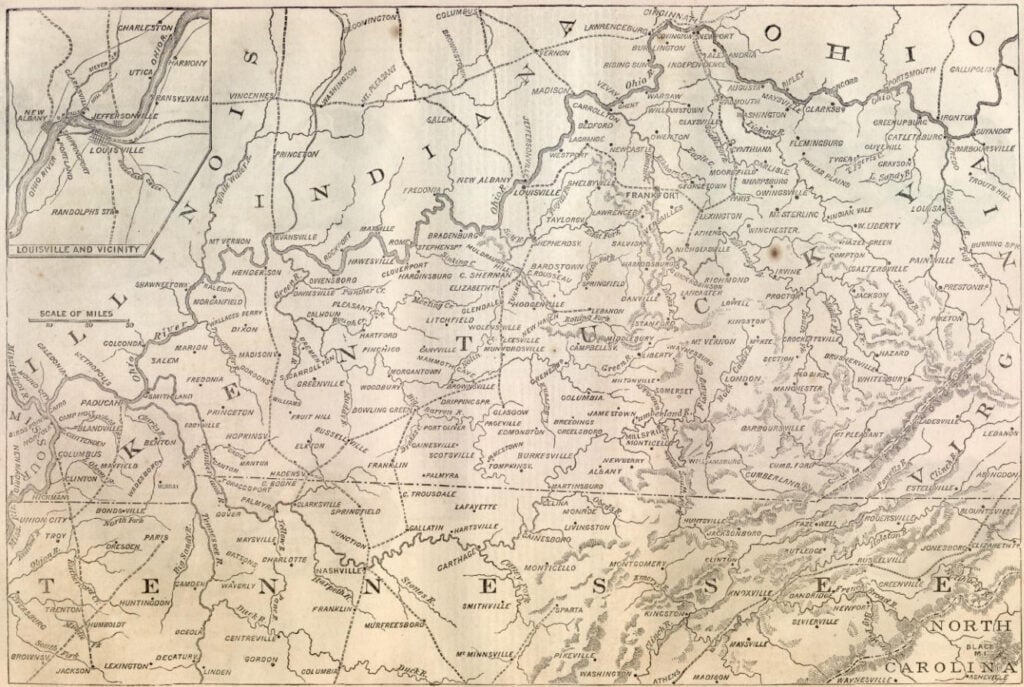

On August 14, 1862, the Confederates began a full-scale invasion of Kentucky when General Edmund Kirby Smith’s Confederate Army of Kentucky marched out of its headquarters in Knoxville, Tennessee. The original plan was for Kirby Smith’s army to drive out the Union forces near the Cumberland Gap, then march back to Chattanooga, Tennessee, to join forces with General Braxton Bragg’s Army of the Mississippi. However, General Smith had no intention of helping General Bragg against the Union forces in Tennessee, led by Major General Don Carlos Buell’s Army of the Ohio. Instead, he marched his army straight towards Lexington, Kentucky (D. Warren Lambert, “When the Ripe Pears Fell: The Battle of Richmond, Kentucky,” 1995, pp. 6-7).

Kirby Smith’s actions would lead him directly to the Union Army of Kentucky, commanded by Major General William “Bull” Nelson. On August 29, 1862, the Confederate forces first contacted Nelson’s army via a small skirmish, leading General Kirby Smith to decide on a full attack the next morning. Unfortunately for the Union forces, Nelson had gone away on business, leaving Brigadier General Mahlon D. Manson in charge. To make matters worse, Manson’s army was composed of inexperienced troops who were not prepared for battle (Lambert, “When the Ripe Pears Fell,” pp. 55-60, 24-25).

The Battle of Richmond was one of the most complete Confederate victories of the war, as General Smith’s forces collapsed Manson’s line. Key to this victory was Kirby Smith’s division of forces — Brigadier General Patrick R. Cleburne attacked the Union line head on, while Thomas J. Churchill utilized a hidden ridge to flank Manson’s right. In the afternoon, General Nelson found his forces in retreat and, despite an attempt to rally them, failed in turning the tide of the battle. Despite the Battle of Richmond being a major Confederate success, its place in history is often overlooked due to it taking place on the same day as the Second Battle of Bull Run (Lambert, “When the Ripe Pears Fell,” pp. 78-88, 180-181; “Gen. Nelson Writes the Following to the ‘Cincinnati Gazette’ in Reference to the Battle at Richmond on Saturday Last and it Strictures Thereon,” “Louisville Weekly Journal,” September 9, 1862, p. 1)

After Richmond, most of Nelson’s forces were taken prisoner by the Confederate army, a success of Colonel John S. Scott’s Confederate cavalry. As a result, General Smith and the Confederates were able to march into Lexington and head toward the state capital in Frankfort. This outcome placed the Union in a desperate defensive position that would cause panic in major cities (Lambert, “When the Ripe Pears Fell,” pp. 150-156, 179-184).

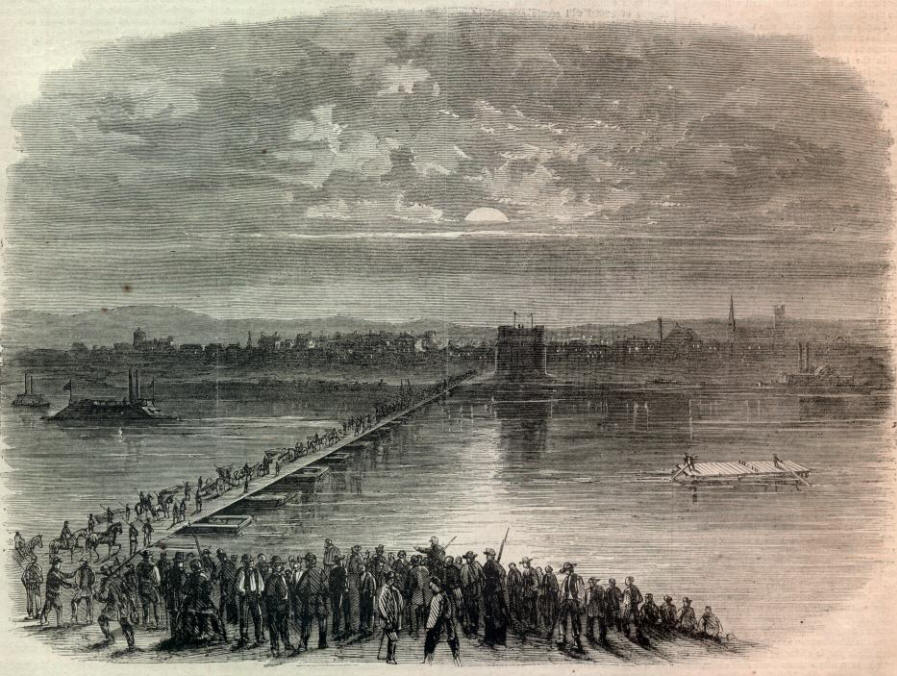

Just over one hundred miles north of Richmond, the major city of Cincinnati, Ohio, was bound to be a target of the dangerously close Confederate army. In addition to Cincinnati’s economic importance to the Union, its place at the midpoint along the Ohio River cemented the city as a probable location for a Confederate attack. With Covington and Newport situated across the river in Kentucky on hills three hundred feet tall, the city was also vulnerable to an approaching enemy’s batteries (Edgar A. Toppin, “Humbly They Served: The Brigade in the Defense of Cincinnati,” “The Journal of Negro History,” vol. 48, no. 2, 1963, pp. 76-77).

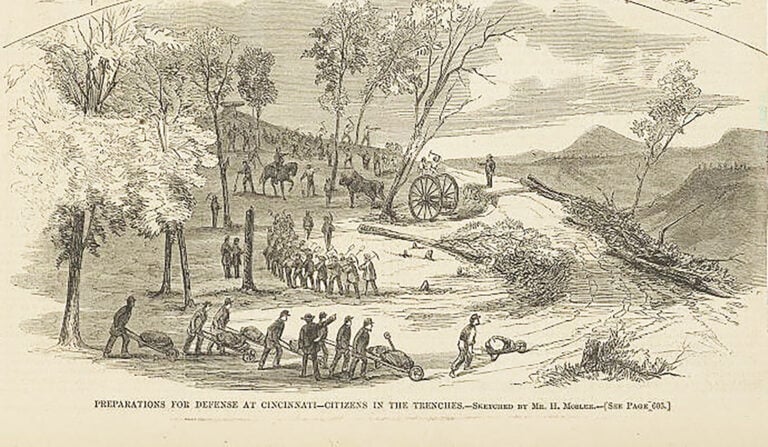

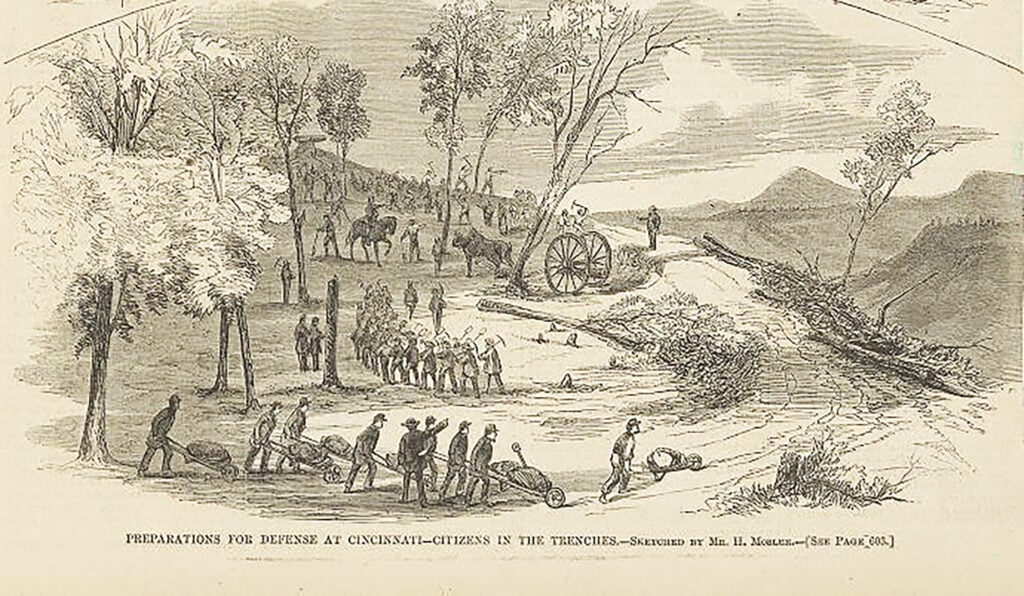

On September 1, 1862, Union Major General Lew Wallace, who commanded the Union Army of Kentucky before it was taken over by General Nelson, arrived in Cincinnati, Ohio. He had been assigned to protect the city from an approaching Confederate force led by Brigadier General Henry Heth. General Wallace immediately declared martial law in the cities of Cincinnati as well as Covington and Newport, calling for civilian laborers. As many as 72,000 residents and volunteers responded to his call (Vernon L. Volpe, “‘Dispute Every Inch of Ground’: Major General Lew Wallace Commands Cincinnati, September, 1862,” “Indiana Magazine of History,” vol. 85, no. 2, 1989, p. 139).

Among the respondents was a group of patriotic African Americans who, after attempting to first volunteer and being rebuffed, were then forcibly conscripted, then subsequently released to return home due to public outrage, and then—in one of the ironies of history—were finally allowed to volunteer. Comprised of over seven hundred men, they were known as the “Black Brigade.” Other volunteers, nicknamed “Squirrel Hunters” due to their lack of experience, were utilized to build fortifications along with a trained military force. Although the citizens of Cincinnati expected a Confederate attack by September 11th, General Heth’s forces were dissuaded by General Wallace’s intense fortifications of the city and withdrew from the area before an attack could be made (Toppin, “Humbly They Served,” p. 76-77, 83-88; Volpe, “ ‘Dispute Every Inch of Ground,’ ” pp. 143-148).

By September 17th, the Union had managed to station three major forces to surround the invading Confederates — one in Cincinnati, another in Louisville, and General Buell’s army in Tennessee. Meanwhile, the division between Kirby Smith’s and General Braxton Bragg’s armies came back to haunt the Confederate armies. Entering Kentucky pursued by General Buell’s forces, General Bragg’s Army of the Mississippi fought the Battle of Munfordville near Louisville from September 14th through 17th. After the Confederate victory, rather than stay in Munfordville, Bragg decided to march toward Bardstown, Kentucky. This opportunity empowered General Buell to make it to Louisville before Bragg (“The Situation in Kentucky,” “Maysville Tribune,” September 17, 1862, p. 2; James Barnett, “Munfordville in the Civil War” “The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society,” vol. 69, no. 4, 1971, pp. 355–359).

After these two armies fought at the Battle of Perryville on October 8th, General Buell routed the Confederate forces back to Tennessee. Sensing lack of support for the occupation from the local population, the Confederates would not launch a full-scale invasion in Kentucky for the rest of the war. Thus, the spoils gained by General Kirby Smith’s resounding victory at Richmond were negated by poor planning from the two Confederate generals. Nonetheless, it was the efforts of Kentucky and Ohio citizens pulling together to defend Cincinnati, along with the subsequent successes of the Union armies, which prevented the 1862 Confederate Invasion of Kentucky from being a total disaster (Lambert, “When the Ripe Pears Fell,” p. 185-187).

James D. Porter III is a graduate student at Northern Kentucky University (NKU). He has a B.A. in History and is currently working toward an M.A. in Public History. Porter can be contacted at jamesdporteriii20@gmail.com.

Paul A. Tenkotte, PhD is editor of the “Our Rich History” weekly series and Professor of History at Northern Kentucky University (NKU). To browse more than ten years of past columns, see https://nkytribune.com/category/living/our-rich-history/. Tenkotte also serves as Director of the ORVILLE Project (Ohio River Valley Innovation Library and Learning Engagement). For more information see https://orvillelearning.org/. He can be contacted at tenkottep@nku.edu.