Editor’s note: This is the second of a two-part series profiling the eleven Kentuckians who have served as U.S. Supreme Court justices. Read the first part here.

By Steve Flairty

Kentucky by Heart

Horace Harman Lurton (1910-1914)

Born in Newport in 1844, young Lurton became a Confederate soldier in the Civil War and was promoted to sergeant major at age 18. He would become a prisoner of war but escaped and joined John Hunt Morgan’s 7th Kentucky Cavalry USA. Ironically, Lurton was taken prisoner again when Morgan surrendered in 1863 during the invasion of Ironton. In captivity, he became seriously ill and his mother persuaded President Lincoln to allow him to come home.

Regaining his health, Lurton attained his law degree and set up private practice in Clarksville, Tennessee, in 1867. He was elected to the state’s Supreme Court in 1886 and became Chief Justice in Tennessee in 1893. In 1909, President Taft nominated him to the U.S. Supreme Court and his performance was considered outstanding. However, he became ill and died in 1914, having served a relatively short stint on America’s highest court.

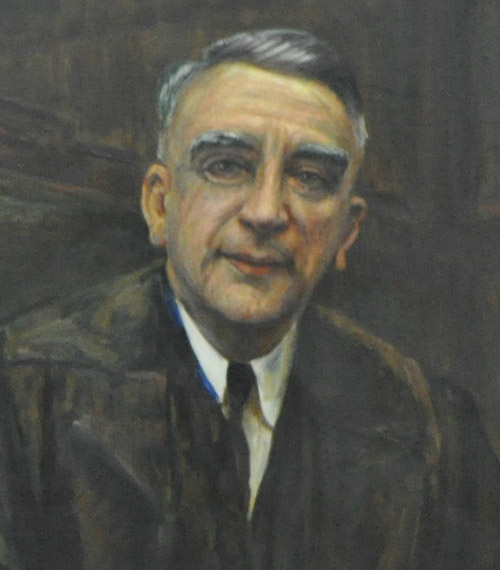

James Clark McReynolds (1914-1941)

An Elkton, Kentucky, native, McReynolds ran unsuccessfully as a Tennessean for Congress in 1896. He taught at the Vanderbilt Law School for several years and later was appointed U.S. attorney general by President Woodrow Wilson. The next year, Wilson put him on the U.S. Supreme Court.

During his tenure of twenty-seven years, he wrote 503 majority opinions, but also dealt 310 dissents. Though originally noted as liberal, the last ten years of his time saw him act more conservatively, with those decisions aimed at slowing FDR’s New Deal policies.

An interesting tidbit about Judge McReynolds, a bachelor, is that during his retirement, he adopted thirty-three refugee children from the war in Europe. He died in 1946 and is buried in Elkton, where he was born.

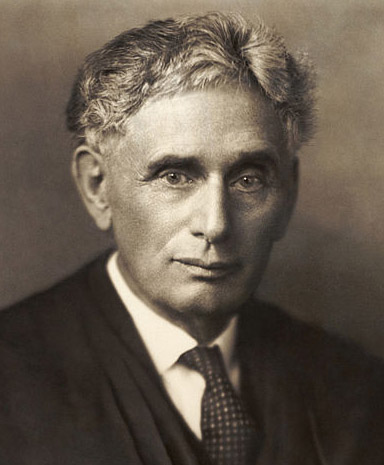

Louis Brandeis (1916-1939)

Louisville native Louis Brandeis traveled America (and even the world) in his work career, but he never forgot his home. As a sixteen-year-old, he left Louisville in 1856 to study abroad in Germany. He came back to America and graduated from Harvard Law School in 1875. He practiced law in St. Louis, then in Boston. Brandeis effectively argued the 1908 case of Muller vs. Oregon before the U.S. Supreme Court, and the Court affirmed a state legislature’s right to regulate the number of hours to be worked by women per day.

President Woodrow Wilson nominated him for the Court in 1916, but Brandies incurred a difficult confirmation hearing. He was confirmed, however, and in his twenty-three years on the bench, his most noted cases were Whitney vs. California (1927), Olmstead vs. United States (1928), and Erie Railroad Co. vs. Tompkins (1938).

Though spending most of his life away from Louisville, he donated much money, books, and personal papers, over 250,000 items, to the University of Louisville Law School. In 1997, the law school became known as the Louis D. Brandeis School of Law, a wonderful tribute to his service to the school and the country.

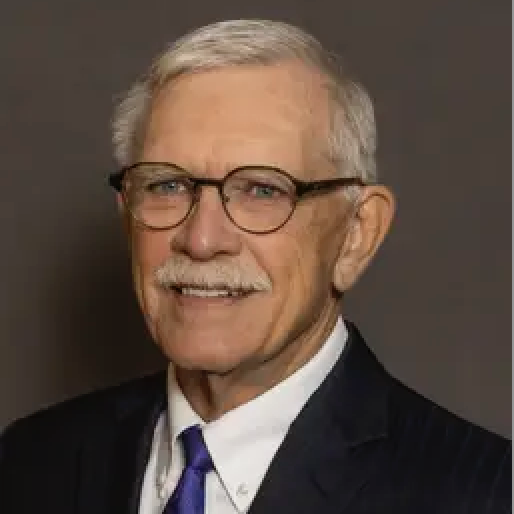

Stanley F. Reed (1938-1957)

From a little town in Mason County, called Minerva, Stanley Reed rose to become the seventy-seventh justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. He set his sights first to gain a college education. It started at Kentucky Wesleyan, then located in Winchester, where he gained an A.B. degree, followed by another A.B. from a faraway place, Yale. He returned to Mason County to read law and was admitted to the Kentucky bar in 1910. Desiring to be publicly involved in service, he ran and was elected to two consecutive terms in the Kentucky General Assembly starting in 1912. He also served as an army lieutenant in World War I.

In the 1930s, Reed held several federal administrative positions in both the Hoover and FDR presidency terms. In 1938, he was nominated for the Supreme Court by FDR and soon confirmed, though he didn’t possess a law degree. He retired in 1957 after participating in more than three hundred opinions, and he was known not to be an idealogue, ruling on each case as being the best outcome. In the iconic Brown vs. Board of Education (1954) case, he voted with the unanimous decision to desegregate.

During his career, Reed maintained a home, farm, and his business interests in Mason County while performing his government duties mostly in Washington, D.C. He died in 1980 in New York but is buried in the Maysville Cemetery.

Wiley Rutledge (1943-1949)

After his 1894 birth in the Ohio River town of Cloverport, Kentucky, Rutledge became pretty much a stranger to Kentucky. He received basic education in Tennessee, an A.B degree from the University of Wisconsin, and his law degree from the University of Colorado. He later would be the dean of the law school at Washington University and later at the University of Iowa. He was placed on the U.S. Supreme Court by FDR and served six years. On the Court, Rutledge gained a reputation as a proponent of civil liberties and a strong supporter of organized labor.

Chief Justice Vinson, another Kentuckian, called Rutledge “true to his ideals and, in all, a great American.” He died in 1949 at age 55, and is buried in Suitland, Maryland.

Fred M. Vinson (1946-1953)

Frederick Moore Vinson became the thirteenth chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court in 1946 after being nominated by President Harry Truman. Vinson was born in 1890, in Louisa. He received his basic education in Louisa, then moved on to Danville where he received a law degree from the Centre law school. During his time at Centre, he played baseball and taught math at the local prep school. He was elected Danville’s city attorney and served until he entered the army in 1918 during the last year of World War I.

Vinson then served multiple terms as a Kentucky representative in Congress and was known as an effective compromiser who got things done. In 1937, FDR appointed him as a judge in the U.S. circuit court for the District of Columbia. The same president then named Vinson to head up his administration’s economic stabilization program. President Truman named him the head of the U.S. treasury in 1945, and he served until Truman appointed him the U.S. chief justice in 1946, where he served until his death of a heart attack in 1953.

The court he presided over is known for dealing with significant cases in racial segregation, labor unions, communism, and loyalty oaths.

Sources: The Encyclopedia of Northern Kentucky; The Kentucky Encyclopedia; Kentuckyoralhistory.org; uspresidentialhistory.com