By Judy Clabes

NKyTribune editor

Tonya Jones will be the first to say she never really had a father, but she had hope — and she hadn’t given up trying.

Now, that hope is gone. Replaced by the anguish of certain knowledge of her father’s brutal death in a Kenton County jail cell on May 14 when he was murdered by a lone cellmate placed with him just hours before.

Johnathan Maskiell, 32, was arrested in Northern Kentucky by Covington police on an outstanding Ohio fugitive warrant on May 13. He had a history of violence and exhibited behavior that suggested a mental imbalance. His visible appearance shows his body covered with tatoos exhibiting Nazi swastika images and violent messages. The message tatooed on his knuckles was: FEAR LESS.

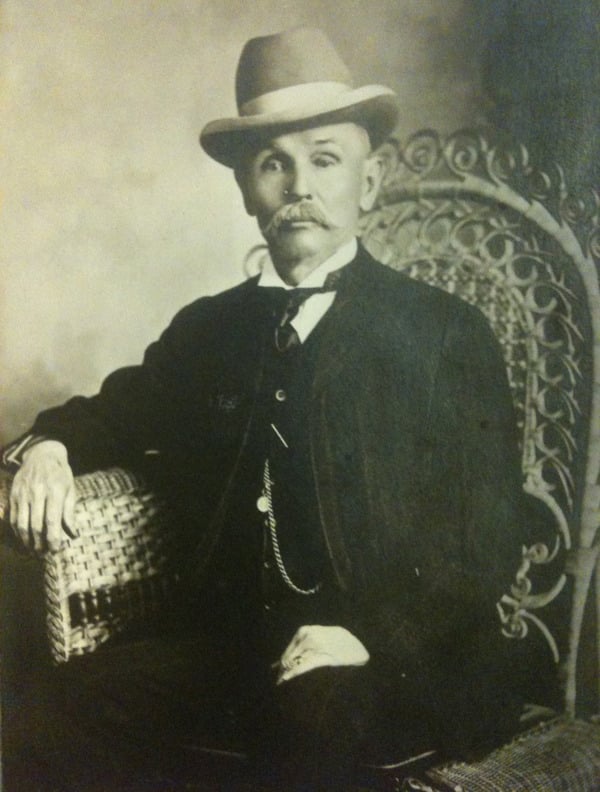

Johnny Daulton, 61, was a chronic offender with no record of violent behavior. In and out of prison all his adult life, he was waiting in a jail cell after being picked up by Covington police for erratic public behavior. He was on a public street wearing one shoe, delirious, and incoherent. He was taken to the hospital for treatment and was released. He went to a relative’s home in Latonia where he was picked up on probation violation charges and taken to the jail. His daughter spoke to him that night and was prepared to pick him up from jail and return him to his halfway house — with the strong admonishment that he had to follow the rules or he was going to go back to prison for his probation violations.

She is haunted by the memory of her last words to him being “mean.”

Daulton was booked in at 8:10 p.m. that fateful Saturday night. Johnathan Maskiell was put into the cell with Johnny Daulton at 4:47 a.m. Sunday morning. The isolated cell had no video surveillance cameras. At about 2:55 p.m., Johnny Daulton was violently assaulted and brain dead. He died a week later without regaining consciousness.

Maskiell told jail employees that “voices” told him to kill Daulton.

No one claims Johnny Daulton was even remotely a candidate for father of the year. In fact, Tonya Jones fought to hold onto the shredded strings of a tenuous relationship. From her earliest days, she remembers a father who floated in and out of her young life, going to jail for theft — and eventually for drug abuse. It was a vicious cycle that in her productive adulthood she hoped she could break.

Jones said, “I loved him in spite of his weaknesses and the wrong he did. I loved him unconditionally.” She clung to a tough love — “because he was my dad.”

Her own story is a checkered one but is the story of a strong survivor whose own parents ultimately became the poster children for how she did not want to live her life. At 14, living with her divorced mom and an atheist stepdad in abject poverty in Newport, she rebelled. Not a pretty rebellion. She left her mother’s home to stay with relatives and ended up pregnant at 16 with a baby boy soon lost to SIDS, then was pregnant again with a daughter at 18 and a son at 19. She was not married but the responsibility of motherhood sent her on a different and better path. She fiercely fought Child Services and the 21-year-old father of her babies for sole custody and won. She found her way through prayer, modeling a faith she saw only briefly in her relationship with her maternal grandmother.

She was determined to be a good mother to her children — and her babies became an inspiration.

“Right is right and wrong is wrong,” she said. “I found my own way to religion and I prayed and prayed to be a good mother to my children — and to love them. I never had that. I learned everything not to do from my parents.”

Jones was also determined to have a relationship with her dad — and naively thought she could help him see his way to a better life. She tried. Yet, he was in and out of jail for theft, drugs, and receiving stolen property over many years.

“The only time he got help was when he was in prison,” she said, “and when he got out he would go back to the same crowd. Prison was his second home. He did better when he was forced to do what he should do.”

Jones today has been married to her husband, Kevin, for 22 years. They live in Pendleton County with their twin boys who still live at home. Her two older children are now grown and are productive citizens — with children of their own. She has drilled into them all the danger of drugs. Jones is a happy grandmother. She is also a registered nurse, having gone back to college, with the full support of her family, when her daughter was 14, her son 11, and her twins 7.

“It was the hardest thing I’ve ever done,” she said, “and it wouldn’t have been possible without the support and love of my family.”

She now works 4-5 days in 12 hour shifts at University of Cincinnati Hospital — and loves her work.

“I wanted to be a good mother and a good provider and lead a productive life.”

She did not abandon her father’s relationship with her children but it was limited based on his condition at any specific time. For instance, in a rare period of freedom from drugs, Daulton taught his oldest grandson how to drive. When he would get back on drugs, he was not allowed to be around her children. She kept pushing him “to do right.”

“I saw the good in him,” she said. “I knew what he could have been . . .but the kind of life he lived was all he knew.”

Most recently, Tonya and her father had planned to get him help for the medical issues he was experiencing due to the life he lead. They had plans in place for his treatment for liver disease.

Today, she just wants to know why things happened as they did at the Kenton County jail but neither she nor her attorneys are getting any answers.

Specifically she wants to know how two inmates were placed in one isolation cell with no video monitoring. Given the age discrepancy and obvious mental issues with violent tendencies present with Maskiell, how could this happen?

In fact, Jones has heard nothing from Kenton County. She didn’t get support for her appeal to the state Crime Victims Advocacy Fund for money to cover her father’s funeral expenses. She was denied because her father was incarcerated when he died. She had to use her credit card to pay those. The cremation is behind her, but her anger is not.

“They are making us go to every extent to get any information,” she said. “I deserve to know how and why he died and what led the jailers to put my sick and weak dad in a jail cell with a violent, mentally unstable man.”

Her lawyers, Deanna Dennison and Paul Hill, also want to know what led jailers to that fateful decision. They have filed extensive requests for information — specifically for the video records of Johnathan Maskiell’s arrest.

“The video we requested will show where Maskiell was and why he was picked up on the warrant and will provide valuable insight into what the police and jail were dealing with that night. There is no reason not to give this to us,” said Paul Hill.

But the official wagons have circled to keep the victims’ advocates out. They cite — wrongly — that they don’t have to share the videos because they are part of an “open investigation” into a murder.

An open records expert says this is a blatant misinterpretation of the law and the Supreme Court has made that abundantly clear.

“The public agencies’ boilerplate denials confirm their disregard for the rule of law and their indifference to the surviving family members — not to mention the public’s — right to know. There can be no corrective action with disclosure of public records documenting this horrific incident and no impediment to disclosure stands in the agencies’ paths,” said Amye Bensenhaver, an expert on open records and a founder of the Kentucky Coalition for Open Government.

“It is difficult to imagine something that is more of a public interest,” Hill said. “Johnny was charged but not found to have violated his drug possession violation. Literally any citizen who is charged and jailed is at the risk that this could happen to them. Any of us. Any of our children charged with a DUI or minor drug possession, anyone. It is among our greatest fears that someone we love, at the mercy of strangers, can be so brutally and needlessly killed.

“Tonya deserves to know what happened to her Dad.”

Deanna Dennison agrees.

“When you are in jail, you should be safe and protected — not just thrown into a cage,” said Dennison. “If the jailers made a mistake, they should own it and stand up to it.

“Tonya Jones has a right to know what happened. It’s wrong not to tell her.”

Johnathan Maskiell’s family was also saddened with the events that led to the violent attack on May 14. One family member posted on Facebook “he was at the hospital for two days before they turned him away; his aunt and mother called the jail and told them he was a danger to his self and others.”

Tonya Jones has reached out to the family in an attempt to find answers regarding the last moments that led to her father’s murder and has requested the help of the Maskiell family. If they are willing to provide information she seeks, they may contact Dennison or Hill or respond to this story.