Cam Miller has a theory.

Actually, baseball historian and independent film-maker Miller, a Covington native and for two decades affiliated full-time with the Cincinnati Reds Hall of Fame and Museum, has lots of theories.

Lots of thoughts about baseball… and the Cincinnati Reds… and Northern Kentucky’s part in making the Reds… well, the Reds.

No better time to explore those than this Opening Day week, which is what Miller did Wednesday evening for a capacity crowd at the annual meeting of the Ludlow Historic Society.

How about this thought: Had it not been for the baseball hotbed that Covington and Ludlow – Dayton, too – were in those post-Civil War years when base ball – two words – exploded in America, there might not be an Opening Day in Cincinnati Thursday.

“Maybe it’s in Indianapolis,” Miller conjectured. But how is that possible? Wasn’t Cincinnati the place that professional baseball was famously invented in 1869 with that unbeaten Red Stocking team featuring the Wright Brothers – Harry and George?

It was, indeed. But when those early professional Reds left town for Boston in 1870, the Cincinnati Red Stockings pretty much folded up their tent and the places where baseball – the professional brand – survived, even thrived around here — Miller contends after thousands of hours poring over newspaper microfilm from that time, were Ludlow and Covington.

It’s an amazing – and mostly lost to history – story that Miller laid out in a series of slides, drawings and commentary. Just short of a film, although not without Miller’s most repeated line of the evening: “I’m going to have to make a film, aren’t I,” after his noted films bringing to life Riverfront Stadium and Crosley Field not to mention Old Latonia Race Track as well as the 1919 Reds World Series’ champs.

Miller, who talks of how “I work alone,” saying he “likes it that way: a department of 1 . . . I do it all.” And no one can call him on it.

And that starts with the research, which had Miller in the Covington library for a film on the Covington Stars team after the Civil War. “And that led me to Ludlow,” he says.

Not to mention the rest of Northern Kentucky. There’s a newspaper story about a “Grand Tournament in Florence” in 1866 – barely a year after the Civil War — where teams from Dayton, Covington, Newport and Ludlow took part. “Every corner up here, every town, every city had a baseball team,” Miller says.

But in the years when the Reds left town and shut down, from 1871 to 1875, there was no pro baseball hereabouts. That is, until Ludlow went pro on April 13, 1875, in a meeting at the Baseball Depot, a sporting goods store in downtown Cincinnati owned by George Ellard, who had started in right field for those original Red Stockings.

Almost immediately, the Ludlow club commissioned the first “riverfront” baseball stadium, at the corner of River Road and West Streets, that would accommodate thousands of fans when they met the Covington Stars for a best-of-three series that summer. At 50 cents a ticket (pro teams doubled the 25 cents charge for amateur games), not a bad haul.

And then Miller displayed other almost surreal sports headlines from that summer: “Bostons vs. Ludlows,” or “Ludlow vs. St. Louis,” or “Ludlow vs. Philadelphia.” No, really.

There’s even a letter from Hall of Fame Reds star Harry Wright asking for Ludlow to play a game hosting his Boston Red Sox that Ludlow lost 17-5. And of note is that in the football-shaped field with a 202-feet right field foul line because of the river, Harry’s brother George Wright, also a former Red Stocking great, hit the first ball into the Ohio River, estimated at just a bit over 400 feet. Not bad in the dead ball, heavy bat era.

The other two dimensions for the Ludlow ballpark were 303 feet in center field and 289 down the left field line. The flagpole in straightaway center was the dividing line with anything hit to the right of it a double, to the left a home run.

One innovation developed in Ludlow, Miller says, for that game against the Red Stockings, when there was so much interest in downtown Cincinnati about how the game was going that they employed a flag man who would signal how many runs – with either a red or white flag – each team had scored. Not exactly tweets but close.

One of the players’ families’ – the McCoys – owned a ferry that brought fans from Cincinnati across the river to Ludlow – hundreds at a time. And a steamboat from Cincinnati arrived with as many as 800 baseball fans.

And so the people who figured it wasn’t worth it to keep the Reds going decided it may be time to re-think that and re-constituted the Red Stockings, who drew a crowd of some 4,500 when they came to Ludlow for an Aug. 9, 1875, game.

Ludlow’s success would be its downfall, however, Miller notes. Because in 1876, the National League (succeeding the previous National Association of professional baseball clubs) would be formed with the original Red Stockings a charter member. And acceding to the Reds’ wishes, they put in a “five-mile clause” saying that no National League teams could play any other pro teams withing five miles in any direction of another National League team.

Goodbye pro baseball in Ludlow and Covington. “A remarkable win for baseball here, even if just for a season,” Miller says. “Ludlow and Covington brought professional baseball back to Cincinnati.”

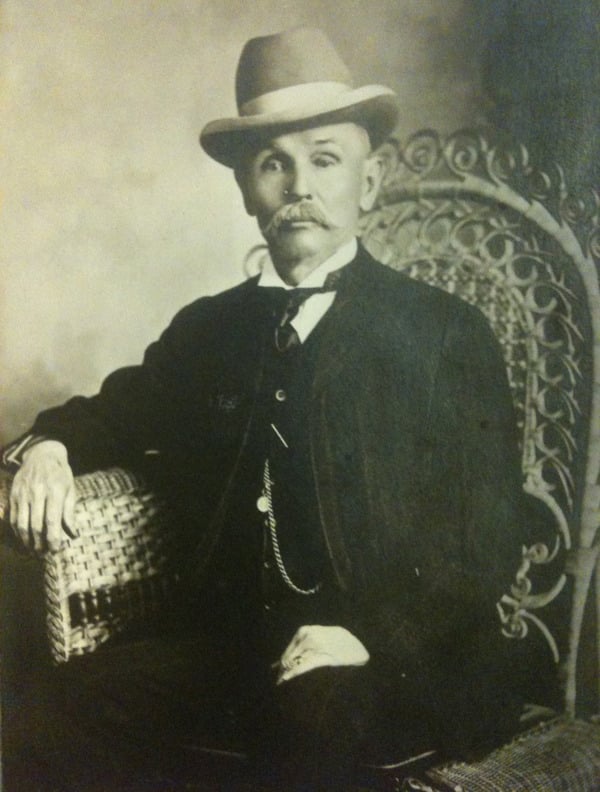

POSTSCRIPT: Just as Miller asked the crowd that “if we don’t pass on history, who’s going to?” and wondered whether he’s going to have to do another film, the history he uncovered makes me ask a similar question. I’ve long had a copy of oldest photo of a Xavier University athletic team – the 1909 baseball team – that featured my grandfather, a lifelong Ludlow resident – Richard Dillon, one of the founders of the Ludlow Building and Loan and a top catcher there in his youth. But thanks to Miller’s research and a look at the early box scores, I learned that one of the stars of those original teams was one Patrick “Packy” Dillon, born in 1853 in St. Louis, who would play both in Ludlow and for St. Louis in 1875. But that also makes me do my own research since our family history has it that at least two Dillon brothers who emigrated from Ireland in the late 1840s, early 1850s came to America – one to Cincinnati, the other to St. Louis. But now, were either of them related to this Packy Dillon? And to me?

And do we all belong to the long baseball line that went through Ludlow?

Contact Dan Weber at dweber@aol.com. Follow him on X (formerly Twitter) @dweber3440.