By Steve Flairty

NKyTribune columnist

It was an oft-forgotten, undeclared war fought by Americans in a foreign country, Russia. Orders came from foreign commanders (British), and those deployed Americans seemed forgotten by their own country. There were no winners for our country, only a bunch of good people following orders and trying to be patriotic.

Likely, many followers of American history would like to forget this episode. Kentuckians would be part of them.

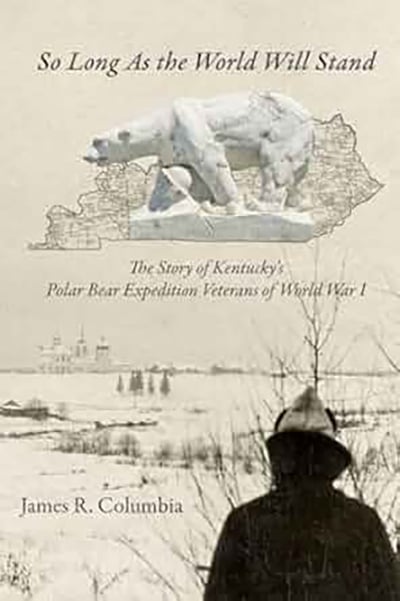

In his 2024 book, So Long as the World Will Stand: The Story of Kentucky’s Polar Bear Expedition Veterans of World War I, James Columbia takes a comprehensive look at the involvement of our fellow Kentucky citizens in this military action, representing our largest cities along with the smallest communities around the state.

The American North Russia Expeditionary Force (ANREF), often called the Polar Bear Expedition, saw our forces engaged from September 1918 to July 1919 on orders from President Wilson. Regrettably, it actually continued after WW I officially ended on November 11, 1918. Americans landed on the soil right smack dab in the middle of a Russian civil war and fought Bolshevik forces who were trying to overthrow the Russian government. Besides the fighting, the weather was often brutally cold, with rough terrain to traverse and medical care lacking. In the end, about 230 Americans died through combat or disease. Because of inadequate documentation, the guess is that about fifteen were Kentuckians.

Of some 6000 Americans, Michigan carried the largest burden of those sent, but over 200 were Kentuckians. By birth, residence, or burial, the Kentuckians represented 106 of 120 counties in the Commonwealth.

Here are the basics of how our country got into this faraway conflict with a portion of Russia’s people. Great Britain and France requested that America join the North Russia Campaign. They gave two reasons: to prevent material stockpiles in Arkhangelsk from falling into German or Bolshevik hands, and along with that, to try to rescue the Czechoslovak Legion, stranded along the Trans-Siberian Railroad.

The objectives were not fully realized, and America would eventually withdraw.

In Columbia’s 657-page book, he shares scores of examples of how the involvement was playing back in Kentucky, sharing newspaper stories and letters sent from North Russia. Very little was of the pleasant variety. Columbia profiled one troop, for example, whom he called “a bitter man.” He was Simon Grant Davis, formerly a teacher from Whitley County and who was called to military service.

An article in the Akron Beacon Journal, described Davis as “only recently returned a broken man from the wilds of northern Russia.” Davis gave damning reports of British officers domineering American officers and lying about the Bolsheviks, understating their well-trained status, leaving the anti-Bolshevik forces unprepared. Davis also reported that Americans, rather than the reported British, were actually holding the front lines.

Columbia notes that Davis’s interview “was one of the earliest public records to document a point of view that would be revisited and corroborated by many subsequent historians.”

The Paris Bourbon News reported on July 8, 1919, that “Fifty-one Kentucky boys have arrived from the Archangel sector in Russia…,” noting that “the boys tell of the hardships the soldiers endured in the frozen north and of many deeds of heroism.”

The article quoted in the book spoke of temperatures there “as much as 60 degrees below zero.” Along that line of reporting, the Frankfort State Journal quoted that one Kentuckian coming back from northern Russia to home said it was ‘like comin’ out o’ Hell into Heaven.”

For me, one of the most fascinating aspects of the book is how Columbia shares names and their connections to Kentucky. In some cases, he supplies pictures.

As one who constantly reads about the state and has traveled extensively, many of the names I encounter seem familiar and encourage me to investigate further the connections I might have. Genealogists, it seems to me, might also be helped by the information.

War — declared or undeclared ones — is hell, and Columbia’s book deserves credit for bringing that message from over a century ago back to us in the Commonwealth now.

A few months back, I wrote a column about Lexington news anchor Marvin Bartlett’s new book, Spirit of the Bluegrass. Marvin characterizes Spirit as “strange, surprising, and sentimental stories from Kentucky.”

The book has been well-received.

Spirit launched on May 6 with more than a hundred people attending a discussion and book signing at Joseph-Beth Booksellers in Lexington. Since its release, it has maintained high sales rankings on Amazon in certain categories and currently is #2 in “General Southern US Travel Guides.”

Marvin has had speaking events in Columbia, Morehead, and Versailles, plus radio appearances in Lexington and Winchester. Here is his upcoming appearance schedule:

• July22: Henderson County Library, 6 p.m.

• August 22: Visit Jessamine Tourism Office, 5 p.m.

• August 30: Estill County Library Book Festival, noon

• September 30: Author’s Roundtable, Mason County Library, 4:30 p.m.

Marvin is excited about the book’s success and perhaps more in the future.

“I’ve been delighted that so many people are interested in these stories about people, places, and traditions that make Kentucky unique,” he said. “People who attend the events have been coming to me with more ideas, so I believe this series will live on for a long time. These aren’t my stories– I’m just fortunate enough to get to put them in writing and pass them along.”

Spirit of the Bluegrass is available widely on online sites such as Amazon and Barnes and Noble. It also is available at Joseph-Beth Booksellers, Lexington. For more information, contact Marvin through his Facebook Fox 56 News page.