The riverboat captain is a storyteller. Captain Don Sanders shares the stories of his long association with the river — from discovery to a way of love and life. This a part of a long and continuing story.

By Capt. Don Sanders

Special to NKyTribune

Of the many years of steamboat history on the Western Rivers, I’m most fascinated with the decade of the 1840s. My fascination may stem from the fact that I am a child of the 1940s, enamored with any numbers belonging to the 40 series. Aside from my enchantment with the 40s sequence of enumeration, transportation during that mid-19th-Century decade West of the Appalachians primarily depended on steamboats until a great war, still a couple of decades away, changed all that.

By 1840, steamboat transportation on the Mississippi River and numerous tributary streams had entered its third decade. In 1811, Nicholas Roosevelt, in command of Fulton and Livingston’s NEW ORLEANS, became the skipper of the first steam-powered vessel to ply the great waters of the West, as Americans called the area from the Appalachians to the Mississippi. Still, by the 1840s, the rivers remained a hazardous course to travel. Snags, sawyers, shallow water, and sandbars still posed challenges to the best pilots, especially on the Lower Mississippi. Exploding boilers, fires, and the frailties of wooden hulls were among other worries that plagued early riverboat transportation.

Early Mississippi River steamboats resembled deep-sea ships. What else did the early boatbuilders have to go on? The newly designed riverboats had deep-draughting hulls, high model bows, and some still sported bowspirits forward of the hulls — all imitations of ocean-going vessels. Practicality, however, soon overcame tradition. Deep-drafting hulls became shallow-drafters, and the bowspirits stood vertical and became a foremast, enabling river pilots a forward reference for navigating.

The 1840s saw a significant contribution to steamboat design. During that decade, an additional deck, known as the Texas, became a standard for steamboat style about the same time that the State of Texas became a member of the United States. Larger and roomier cabins on that deck became associated with Texas, then the largest state in the Union.

Although photography was still in its infancy in the 1840s, at 1:45 p.m. on September 24, 1848, two daguerreotypists from Cincinnati, Ohio, Charles Fontayne and William Porter, produced one of the most well-known series of photographs of the medium. On eight daguerreotype plates, the duo captured the first photo-images of steamboats as they lay moored at the Cincinnati waterfront on a lazy Sunday afternoon.

My favorite is Plate 3, which captures the Packet BROOKLYN lying alongside two unidentified steamers. Behind them, ashore, is the mahogany woodworks of Henry Albro, the husband of the builder of the exquisite Covington, Kentucky, Eastlake Italianate townhouse, the Harriett Albro House, the first home I owned. I’ve lost track of the many times I wished I could slip across the threshold of these photographs and be there amongst all that the master daguerreotypist captured that day.

The Cincinnati F&P Daguerreotype also played a significant role in archiving steamboat history. In 1947, the steamboat Pilot, Master, and Owner, Captain Frederick Way, Jr., and Cincinnati Public Library director Carl Vitz began a comprehensive historical investigation of the daguerreotype, using steamboat records to identify the only date on which all of those vessels were in Cincinnati at the same time: September 24, 1848, at just before 2:00 p.m. Later, proof of their conclusive estimate of time received verification after conservators at the George Eastman House of Rochester, New York, finished the restoration of the historic photographic plates. Their work enabled them to read the face of a clock tower on one of the plates, reading exactly 1:55 in the afternoon.

The 1848 Daguerreotypes became the starting point when Captain Way began compiling information in his now indispensable “Way’s Packet Directory, 1848 – 1994” of steam packetboats on the Western Rivers. So, why did he choose 1848 as the starting date when steamboats had been around on the Mississippi River System since 1811? Was it because of the famous Cincinnati daguerreotype?

When I queried the author and grandson of Captain Way, Mr. Fred Rutter, he replied:

“Yes, that is the sole reason. Captain Way wanted to have photos of the boats available for his research and verification process. Records of boats existed before the photographic era, but they were often confusing and inconsistent. Photos answered questions.”

In Captain Way’s Preface to my much-worn copy of his Packet Directory, he, himself, explained:

“The earliest known daguerreotype steamboats on the Ohio, or any other Western Stream, dates 1848, the year when Charles Fontayne and W. S. Porter created a panorama of the Cincinnati waterfront… so that is my starting point, 1848, and my knowledge of earlier ones is sparse.”

Captain Fred further noted, however, that between 1811 and 1847, some 900 steamboats paddled on the Western Rivers during those years. Then he further observed:

“Paintings, sketches, and drawings exist of some of these, leaving me with the impression that many of the early artists were poor marine architects.”

As I explained before, I cannot recall how many times I wished I could be in the scenes captured by the 1848 daguerreotpyes in the old Cincinnati that I knew and loved over a century later when the same buildings still existed, though mostly empty and forlorn before their destruction for the Third Street Distributor, now the Pete Rose Way.

Outside, on my front porch, is a handmade metal five-pointed star that once graced a building that stood in 1848. My star, now painted yellow-gold, honoring the Sun, may be one of the few known remnants from all of the structures captured in the historic Cincinnati daguerreotype, other than the rubble from those ancient buildings dumped over the riverbank to enlarge the parking lot of old Walt’s boat Club in West Covington, below the end of the floodwall.

As Captain Fred Way noted, portrayals of steamboats made before the 1848 photographic panorama are quite rare and unreliable. When I consulted my collection, which includes perhaps 50,000 steamboat and river-related photos, looking for a steamboat from the 1840s, a few pictures emerged. None were of boats of that era, but rather the name emerged of a celebrated American photographer born in 1843 who lived into my lifetime in the 1940s, William Henry Jackson.

William Henry Jackson was a photographer, Civil War veteran, painter, and explorer of the Old West. He also photographed several steamboats from the early 1900s, which are now in my archives. His photo of the Steamer NATCHEZ, built in 1891 by Howard Shipyard in Jeffersonville, Indiana, which I’ll share, is breathtaking. This NATCHEZ, best remembered for its female Master, Captain Blanche Douglas Leathers, the daughter-in-law of the memorable Captain Thomas P. Leathers, was a sternwheeler. Captain Tom, a native of Covington like myself, may best be remembered for commanding the NATCHEZ # 6, which raced the ROB’T E. LEE in June 1870.

Returning to the 21st Century after a foray through the 1840s along the river usually seems disappointing until I recall that Fontayne and Porter’s daguerreotype also revealed an open sewage ditch running from a building on Front Street to the river. The following year, the Great Cholera Epidemic of 1849 proved to be devastating, with over 8,000 deaths in the tri-state area around Cincinnati alone. But that’s another story for another time.

Captain Don Sanders is a river man. He has been a riverboat captain with the Delta Queen Steamboat Company and with Rising Star Casino. He learned to fly an airplane before he learned to drive a “machine” and became a captain in the USAF. He is an adventurer, a historian and a storyteller. Now, he is a columnist for the NKyTribune, sharing his stories of growing up in Covington and his stories of the river. Hang on for the ride — the river never looked so good.

Captain Don Sanders is a river man. He has been a riverboat captain with the Delta Queen Steamboat Company and with Rising Star Casino. He learned to fly an airplane before he learned to drive a “machine” and became a captain in the USAF. He is an adventurer, a historian and a storyteller. Now, he is a columnist for the NKyTribune, sharing his stories of growing up in Covington and his stories of the river. Hang on for the ride — the river never looked so good.

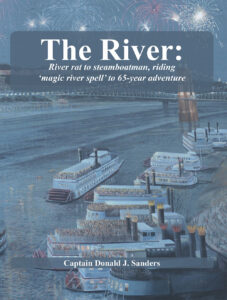

Purchase Captain Don Sanders’ The River book

Capt. Don Sanders The River: River Rat to steamboatman, riding ‘magic river spell’ to 65-year adventure is now available for $29.95 plus handling and applicable taxes. This beautiful, hardback, published by the Northern Kentucky Tribune, is 264-pages of riveting storytelling, replete with hundreds of pictures from Capt. Don’s collection — and reflects his meticulous journaling, unmatched storytelling, and his appreciation for detail. This historically significant book is perfect for the collections of every devotee of the river.

You may purchase your book by mail from the Northern Kentucky Tribune — or you may find the book for sale at all Roebling Books locations and at the Behringer Crawford Museum and the St. Elizabeth Healthcare gift shops.

Click here to order your Captain Don Sanders’ ‘The River’ now.