(Editor’s note: We’re celebrating ten years of Our Rich History! You can browse and read any of the past columns, from the present all the way back to our start on May 6, 2015, at our newly updated database here.)

By Paul A. Tenkotte, PhD

Our Rich History editor

In the 1800s women lacked many civil rights enjoyed by their fellow male U.S. citizens. For instance, they were largely barred from voting and property ownership, except in limited cases. Vocational, educational, and employment opportunities were also restricted. Women’s achievements are especially notable given the significant challenges they faced.

Julia Margaret Mallot Milligan (1824–1903) was a successful woman who overcame the odds against her. Born in Cincinnati, Ohio, on December 31, 1824, she spent her early life in the region and by 1840 in the historic Ohio River working class town of Fulton on the city’s east side. By 1850, she and her husband, Samuel Robert Milligan (1818–1886), were living next door to her parents, Isaac and Caroline Mallot, on Front Street in Fulton opposite the Jamestown (Dayton, KY) ferry landing (Ancestry.com; “Williams Cincinnati Directory, 1850–1851”).

Julia’s husband Samuel was a “moulder,” that is he worked with patterns (“molds”) at his own iron foundry — Milligan and Clements — on the south side of Congress Street east of the Miami and Erie Canal in Cincinnati. By 1850 Julia and Samuel already had four children, William, Charles, Julia, and Floretta (1850 US Census).

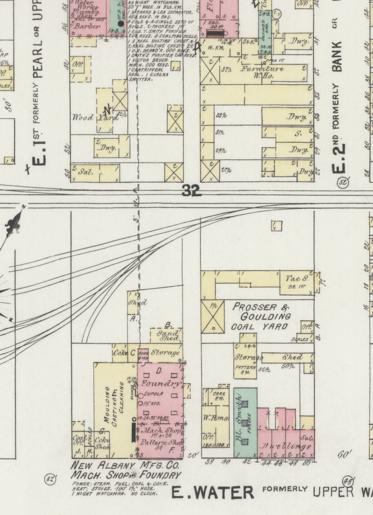

The early 1850s found Julia and Samuel Milligan moving to the Ohio River city of New Albany, Indiana, opposite Louisville. There, Samuel worked in iron foundries, serving as foreman of the city’s well-known Phoenix Foundry. In 1866 he built a massive new foundry of his own on Water Street near Pearl. The “New Albany Daily Ledger” described him as “a practical machinist and moulder, and as such enjoys a wide spread [sic] reputation. He will not be long, when his establishment gets into operation, in building up a very large and remunerative business” (“New Albany City Directory and Business Mirror,” 1859; “New Foundry,” “New Albany Daily Ledger,” February 14, 1886, p. 2).

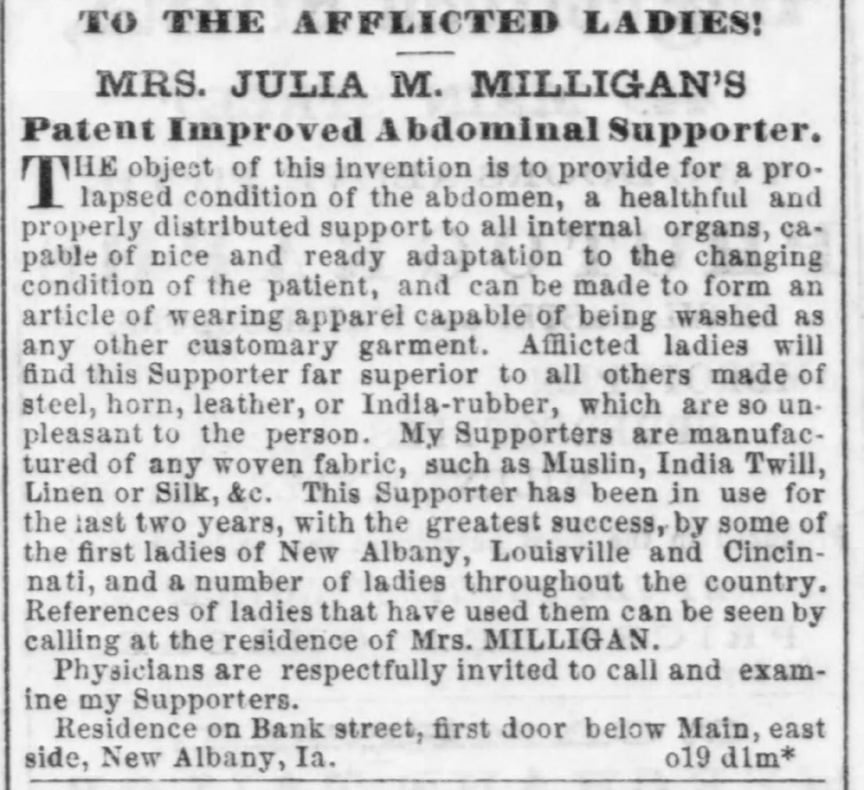

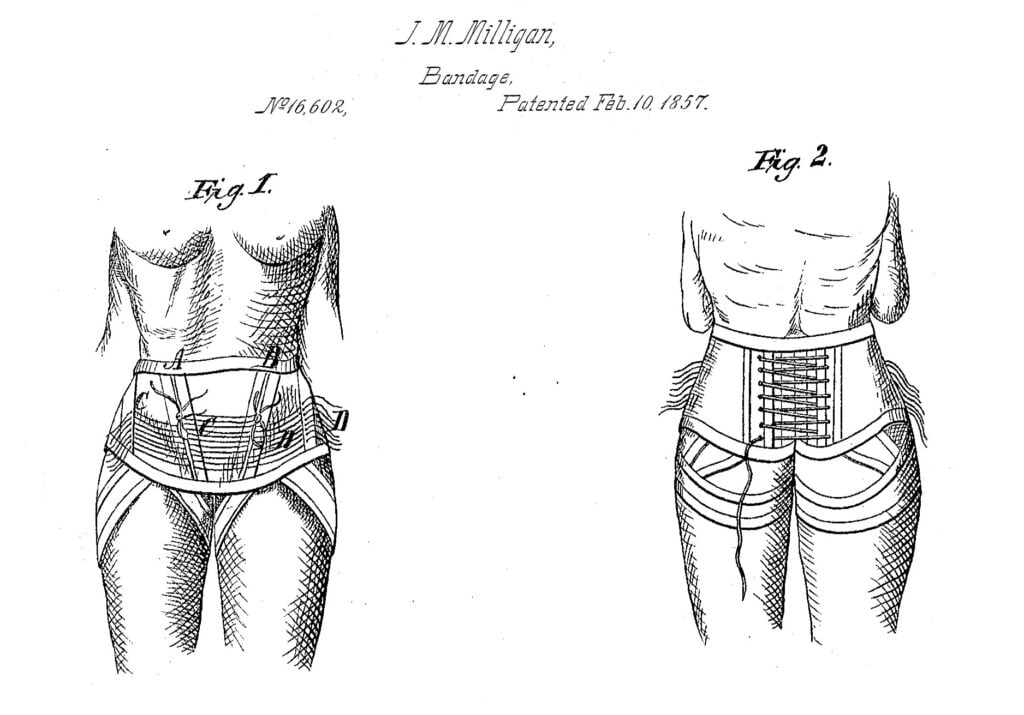

In 1857 Julia Milligan received US Patent #16,602 for a significant invention that assisted women suffering from abdominal prolapse, more commonly known as pelvic organ prolapse. Unlike other supporters on the market, made of uncomfortable materials such as “steel, horn, leather, or India-rubber,” Milligan’s was “manufactured of any woven fabric, such as Muslin, India Twill, Linen or Silk,” providing a “healthful and properly distributed support to all internal organs.” In addition, it was adaptable “to the changing condition of the patient.” And like any “article of wearing apparel,” it was washable too (Advertisement appearing in the “Louisville Daily Courier,” October 21, 1858, p. 2).

Julia’s abdominal supporter appeared to be a very lucrative invention, judging from the hundreds of advertisements she purchased in New Albany, Louisville, and Cincinnati newspapers in the late 1850s. In the 1859 “New Albany City Directory and Business Mirror,” she even had her own business listing: “MILLIGAN, Mrs. JULIA M., proprietress of the patent improved abdominal supporter.” Her husband’s foundry was also flourishing. In April 1871, for instance, the “Cincinnati Enquirer” reported that “Mr. Samuel Milligan, the well-known foundryman” of New Albany returned from Madison, Indiana, “where he purchased the entire stock of patterns of the Neal Foundry,” including “all kinds of cylinders, from thirty-inch down to the smallest land engine” (“News from Other Ports,” “Cincinnati Enquirer,” April 4, 1871, p. 7).

While living in New Albany, the Mulligans welcomed three more children into their family, George, Mary Ella, and Mary Luella. However, the good times would soon fade. While the “Louisville Courier-Journal” reported in May 1871 that Milligan’s foundry had obtained the contract for the machinery for a new packet boat called the “Grey Eagle” being built in the Howard Shipyard in Jeffersonville, Indiana, his business soon declined. By July, the “Courier-Journal” announced that Milligan’s foundry had “suspended operations” and had transferred the “Grey Eagle” machinery contract to “Ainslie and Cochran, of Louisville.” And by September 1871, Milligan declared bankruptcy, and his foundry was put up for auction the following year. In the next month, October 1871, Julia’s father Isaac died in Cincinnati (“Louisville Courier-Journal,” May 7, 1871, p. 2; “Louisville Courier-Journal,” July 15, 1871, p. 4; “New Albany,” “Louisville Courier-Journal,” September 26, 1871, p. 1).

Then in 1873 an economic depression collapsed the economy, lasting until 1878. The Milligan family returned to the Cincinnati area. Samuel Milligan became an advocate for workingmen and their families, helping to establish chapters of mutual aid societies throughout the region. He even served as Supreme President of the Independent Order of Workingmen. By the 1880s, he was an active leader in the Knights of the Golden Rule (KGR), which provided death benefits for their members. During the destructive Ohio River flood of 1884, he “had charge of one of the relief” efforts, distributing “food to over four hundred families daily” in Cincinnati east end. In March 1866, Samuel died at his home in Bellevue, Kentucky, and was buried in Evergreen Cemetery in Southgate (“Independent Order of Workingmen at Wheeling,” “Cincinnati Enquirer,” May 18, 1878, p. 5; “Knights of the Golden Rule,” “Cincinnati Enquirer,” March 9, 1884, p. 16; “Newport,” “Cincinnati Post,” March 18, 1866, p. 1).

In 1900 the machinery of a successor foundry and machine shop of Milligan’s — the New Albany Manufacturing Company — at Pearl and Water Streets was moved to its new location at East Tenth and Water Streets in New Albany. The “Louisville Courier-Journal” reported that the foundry “was erected thirty-five years ago by the late Samuel Milligan, and it has been used as a foundry and machine shop all these years. From its dilapidated walls have been turned out many of the powerful engines that have furnished the speed for the great steamers that were in use over twenty years ago in the lower [Ohio] river” (“New Albany,” “Louisville Courier-Journal,” September 5, 1900, p. 5).

Julia Milligan lived for another seventeen years after her husband’s death. On March 1, 1903, she died at the home of her youngest daughter, Mary Luella Smryl (1859–1937), in Bellevue and was buried in Evergreen Cemetery. Her obituary appeared in newspapers throughout the region, including Cincinnati, Covington, Louisville, and New Albany.

Julia Milligan is one of the many inventors showcased at the upcoming Entrepreneur & Small Business Day hosted by the Kenton County Public Library’s Erlanger Branch at 401 Kenton Lands, Erlanger on Wednesday, September 17,.

Paul A. Tenkotte, PhD is Editor of the “Our Rich History” weekly series and Professor of History at Northern Kentucky University (NKU). Browse ten years of past columns here. Tenkotte also serves as Director of the ORVILLE Project (Ohio River Valley Innovation Library and Learning Engagement). For more information see orvillelearning.org. He can be contacted at tenkottep@nku.edu.