By Dennis Whitehead

Special to NKyTribune

Part 1 of 2 parts

Sixty years ago, a killer was on the loose in Cincinnati precisely at a time of great upheaval in the United States.

Nine-thousand miles from Cincinnati, America was increasing its military commitment to a civil war in faraway Vietnam that was rapidly becoming a proxy war of major powers. In order to fulfill the growing military needs for manpower, President Lyndon Johnson reinstated conscription. Opposition to the draft was exemplified by young men burning their draft cards. Tens of thousands marched in opposition to the draft and the war in major cities. In downtown Cincinnati, police estimated forty protestors marched, most of whom, they said, came from Antioch College. They were met by counter-protestors from the National Association for the Advancement of White People.

The World War II generation was encountering a new breed in American youth who questioned authority. Distrust of police spread.

American cities were choking in a fog, coined “smog” at this time. Industrial Cincinnati spewed foul air with the occasional mix of Ivory Snow. Water often had to be boiled thanks to chemical spills in the Ohio River.

Civil rights activists marched and rode buses across the American South peacefully demanding basic rights for the nation’s Black citizens, facing White-driven violence in return. The Civil Rights movement realized a victory in the 1965 passage of the Voting Rights Act but that was only realized out of widespread shock at the brutality of police toward peaceful marchers in Selma, Alabama on Bloody Sunday.

The non-violence preached by Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. and other civil rights leaders was fraying as younger activists took a more militant stance. The new firebrands, such as Stokely Carmichael, took control of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) from John Lewis, a civil rights champion and later a respected member of the U.S. Congress, to advance Carmichael’s call for “Black Power.”

Peaceful solutions to racial strife in American cities were giving way to riotous violence in major urban centers.

Cincinnati was a quiet, conservative Midwestern hub that felt some distance from the anxieties afflicting the nation, but that was about to change as Cincinnati would lose its innocence.

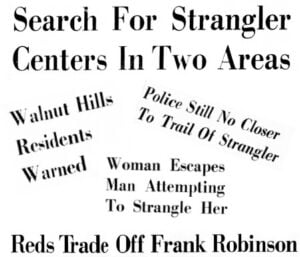

From December 1965 to December 1966, six women, aged 51 to 81, were strangled to death across the city — East Walnut Hills, Price Hill, Burnet Woods, the Gaslight District in Clifton, Vine Street Hill, and downtown. They were strangled with a variety of ligatures: a plastic clothesline, nylon stockings, a bathrobe sash, a tattered necktie, and an appliance cord. All suffered blows to the head, some disfiguring, and one badly beaten about the torso breaking multiple bones. All but one showed evidence of post-mortem sexual abuse. Fear and suspicion spread deeper into the city’s psyche with each murder.

When the body of 56-year-old Emogene Harrington was found with a plastic clothesline tied around her neck on the floor of the dingy basement bathroom in The Claremont apartments on December 2, 1965, police quickly noted a possible connection to recent assaults of older women in East Walnut Hills. They suspected one man was responsible for all of the crimes.

That neighborhood connection was broken on April 4, 1966, when 58-year-old Lois Dant was discovered by her husband lying on their Price Hill apartment floor. A stocking taken from the bathroom was drawn around her neck.

Next, on June 10, the nude body of 55-year-old Mathild Messer was found lying in the brush alongside a trail in Burnet Woods, a tattered necktie was used to strangle the life from her.

The string of murders, and the attendant media attention, struck fear into women across Cincinnati, each certain she could be next. Locksmiths were kept busy installing extra security to doors. Shopping and luncheon plans were postponed out of fear of The Strangler. Sporting goods stores reported brisk sales of firearms, caution being urged by police.

The September 26th stabbing murder of the three members of the Bricca family in suburban Bridgetown heightened fears that murder was omnipresent, even if there was no connection to the strangulation murders.

On the morning of October 12th, 51-year-old Alice Hochhausler was found lying on the driveway of her Gaslight District home by her husband. The mother of nine had been strangled with the sash of the bathrobe she’d been wearing when she picked up her daughter from Good Samaritan Hospital where she worked as a nurse. She didn’t want Beth walking home in the shadow of a killer.

The brutal death of Alice Hochhausler intensified citizen demands for the killer to be apprehended. Pressure was brought to bear on local politicians who passed it along to police leadership who let rank and file know they must find the killer, and fast!

Continued next week

Dennis Whitehead is a writer and photographer in the Washington, DC area. A Cincinnati native, Whitehead is the author of several books from the wars of the 20th Century but was drawn back to his childhood to recount the stories of the Cincinnati Strangler in the nonfiction true crime book, of the same name, drawn from the original police investigation files, court transcripts, and prison records.

The Cincinnati Strangler: Murder and Mayhem in the Queen City (ISBN 979-8-9992298-0-9 / Amazon ASIN: B0FPMJJMQ7). The print edition ($29.95) is available in Cincinnati, at Joseph-Beth Booksellers and Cincy Book Rack, but just ask your favorite bookstore and they’ll know where to find it. The book is also available as an ebook ($19.95). If anyone has trouble finding a copy, they can contact the author directly at denniswhitehead@gmail.com.

Paul A. Tenkotte, PhD is Editor of the “Our Rich History” weekly series and Professor of History at Northern Kentucky University (NKU). To browse more than ten years of past columns, click here. Tenkotte also serves as Director of the ORVILLE Project (Ohio River Valley Innovation Library and Learning Engagement). For more information see https://orvillelearning.org/. He can be contacted at tenkottep@nku.edu.