Editor’s note: This is the third in a four-part series celebrating the Quasquicentennial (125th) anniversary of the Dedication of St. Mary’s Cathedral — Cathedral Basilica of the Assumption — on January 27, 1901. (For previous parts, click here.)

By Stephen Enzweiler

Special to NKyTribune

On April 8, 1890, James Walsh, Sr. died suddenly from a fatal stroke at his residence in Washington, D.C. An immigrant from Ireland, Walsh had lived in Covington and Newport since 1848, entering the employ of a distillery business and rising to become a partner in 1867. Owner of the James Walsh & Company Distillery, he was a wealthy citizen and philanthropist, a supporter of Catholic charities and institutions across Cincinnati and Northern Kentucky, and a lifelong parishioner of St. Mary’s Cathedral in Covington. At the time of his death, he was one of the wealthiest men in America. In his Last Will and Testament, he left bequests in large amounts to ten Catholic beneficiaries, including “the sum of twenty-five thousand dollars” to the Rt. Rev. Camillus Paul Maes, “for use and benefit of a new St. Mary’s Cathedral at Covington.”

The $25,000 for the new cathedral was the largest of Walsh’s bequests, and within days all the newspapers across the region carried the many details of his generosity. His example occasioned others to make their own donations to Bishop Maes for the new Cathedral fund. Throughout that year, the money steadily came in, and by November, according to the “Catholic Telegraph,” “the total of the bequests amounted to $90,000.” With the cathedral parish itself having already agreed to pay $75,000 of the cost from their own pockets, it brought the total available means for construction of a new cathedral to $165,000, which was more than the roughly $150,000 the bishop thought it might cost.

For five years, Bishop Maes had been praying for a solution to his new cathedral problem. There were many dark days when he felt that he would never be able to afford such a house of worship as was his wish, and with each passing year, the cost of building materials and labor increased. Sometimes it seemed a new cathedral might never be built.

Yet, it seemed a bit like a dream to him in many ways. Maes often thought about how he came to Covington … the random choice of the Pope and how Maes seemed to have just the right skills and talents for what needed to be done at that time in the Diocese of Covington. And then there was the little girl who visited him in 1886 with her unusual request.

Described in a “Kentucky Post” interview with the Bishop years later, the young girl placed into his hand a shiny, newly-minted silver dollar and told him to “take it and build a new cathedral in Covington.” He viewed this innocent request as a providential sign. Maes believed that God often spoke to adults through children, as demonstrated in Marian apparitions of previous years—at Celles (1842) in his native Belgium, at La Salette (1846), Lourdes (1858) and Pontmain (1871) in France, and at Marpingen (1876) in Germany. According to the “Kentucky Post” story, he took the little girl’s gesture as the sign of a providential commission. “From that hour,” the “Post” reported, “Bishop Maes determined to act upon the suggestion of the child, and from that day he has labored without rest to accomplish the task the child had given him to do.”

Now with funds in hand, Bishop Maes found himself facing two very large questions: where to locate the new cathedral, and what kind of cathedral should it be? To the first question, he chose to place the new St. Mary’s Cathedral at what was then considered the center of the city—the corner of Twelfth Street and Madison Avenue. Two properties were already situated there—the residences of Dr. John Delaney and the McVeigh family. And when the opportunity presented itself, he purchased both, giving him a large footprint on which to build.

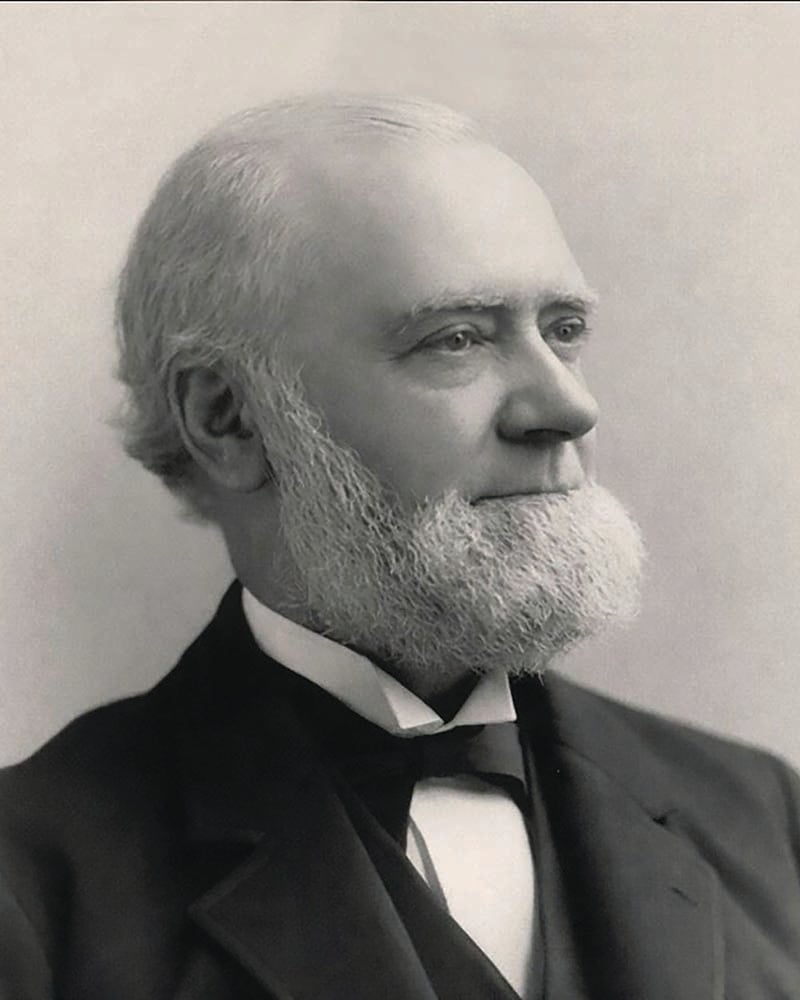

By this time, Leon Coquard in Detroit had become a prosperous architect in his own right. He left the firm of Albert E. French in 1887 after the completion of St. Anne’s Church and set out on his own. His reputation seemed well established, as he was rarely without work after that. Up to this point, he had been designing residential homes, commercial buildings and schools, such as the posh and spacious neo-Gothic homes of Detroit’s famed Indian Village or the sprawling Saint Peter and Paul Academy in Midtown. But it didn’t satisfy him as greatly as did his work on St. Anne’s, and he longed for a great commission to design something that would make him an architect of consequence.

Maes didn’t yet know what kind of Cathedral he wanted to build, but his thoughts kept drifting back to his 1888 visit to St. Anne’s Church and the deep impressions it left on him. As a result, he had long ago settled on Leon Coquard as the architect he wanted to build his new Cathedral and never solicited competitive bids from any other architects.

In June 1891, Bishop Maes was ready to proceed and penned a letter to Coquard asking for his terms of contract. “The fact that I select you without competitive plans is because I am pleased with your art and work,” he wrote. “I consider that your terms … for preliminary sketches, definite drawings, working plans, specifications and details, are very low. Hence, I accept your terms; and foreseeing that you will give me the best work you are capable of, I feel that I am your debtor.”

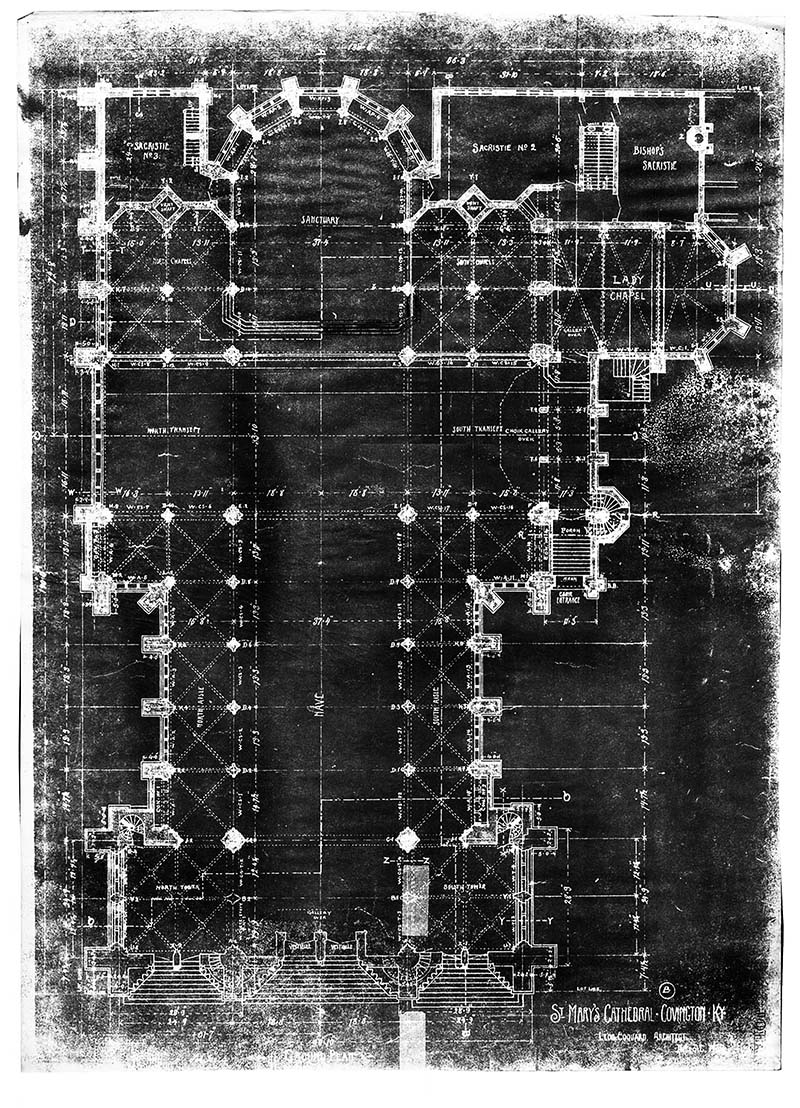

It would be another year before the two men began a serious collaboration on the specifics of the cathedral project. In a letter dated June 10, 1892, Bishop Maes laid out his basic preferences for what he would like to see in his new Cathedral. His worry over not having enough money at the outset prompted him to first suggest constructing “a lofty basement church to be used for the next two or three years or longer.” He eventually saw the folly in it and yielded to Coquard’s insistence on erecting a full-scale building. Maes proposed simply that the new Cathedral should be cruciform in its floorplan, with the apse facing east and the front “facing Madison Avenue, with a stone front, the balance of the building, Gothic style.” The rest of the details he left up to Coquard.

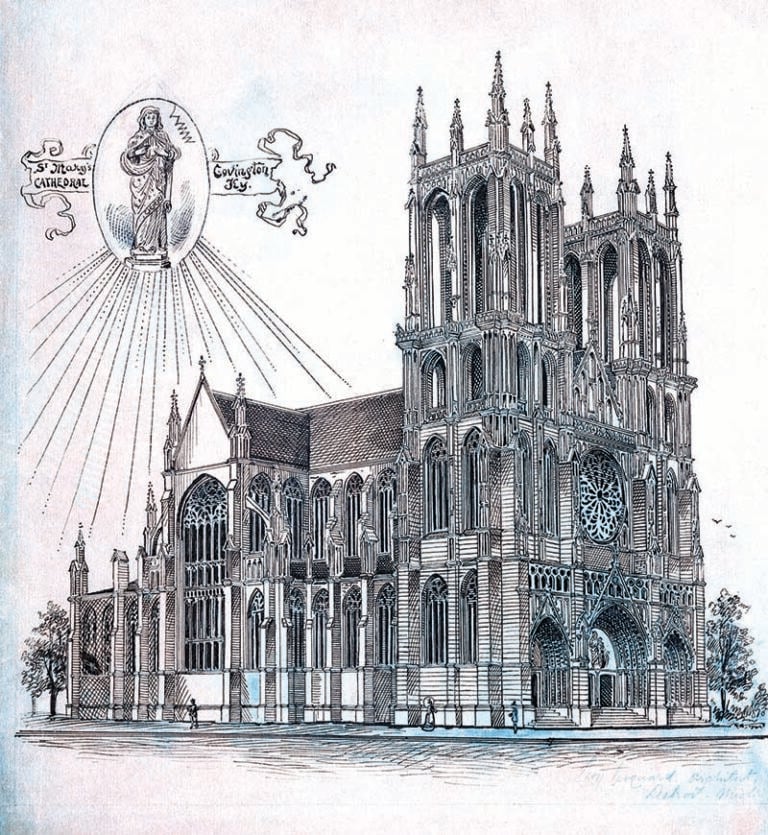

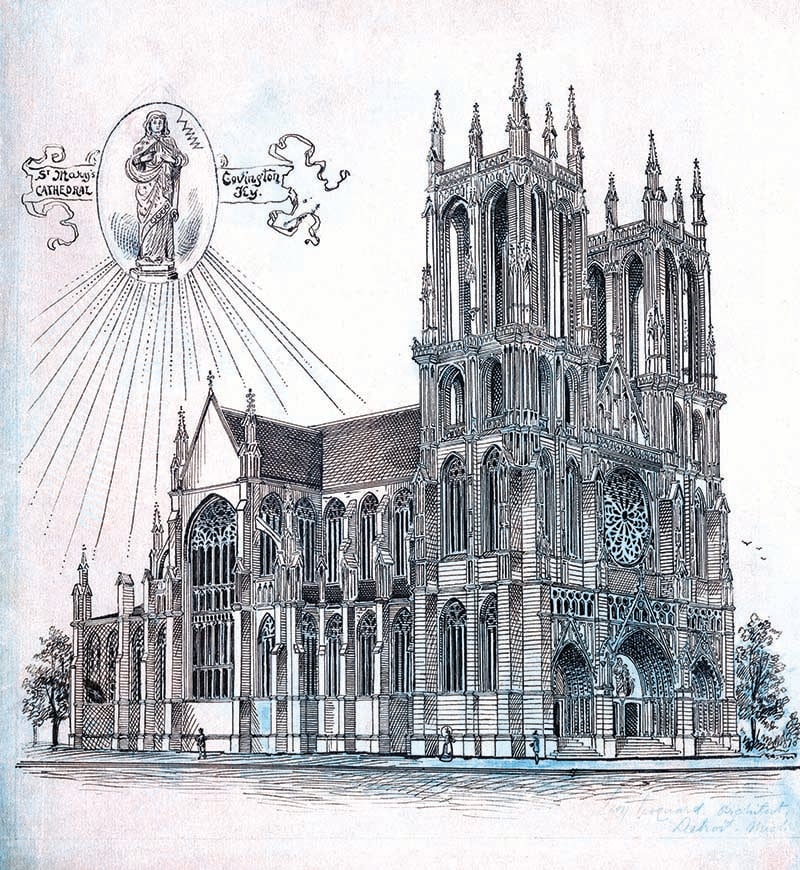

Within weeks, the architect sent him a watercolor sketch, followed by a detailed pen and ink rendering of the proposed new structure. It was a highly ambitious concept, incorporating the bishop’s requests, but also presenting Coquard’s own creative vision for what he liked to call “the pure French style of Gothic Architecture.” The main body of the church was High Gothic in its style, with flying buttresses wrapping around both sides and large rose windows and gables to give one the impression of Notre Dame de Paris. The façade was a more complex blending of Rayonnant and Flamboyant styles, with tall, open bay bell towers liberally ensconced with pinnacles, crockets and finials.

It was beautiful, but it frightened the frugal Maes. “The trouble is,” he lamented to his architect, “that those who appreciate true art are often the very ones who are too poor to pay for it; and I am sorry to say that this is my case and is the reason I reluctantly underwent the mortification of asking for lowest terms.”

The two men spent the rest of 1892 and much of the following year in back-and-forth exchanges, both compromising on details, adding new features and removing others, refining and distilling it all down until they were comfortable with the result. With Maes’ approval, Coquard chose the interior of St. Denis Cathedral in Paris, and its apse inspired by the apse of the Cathedral of Notre Dame de Ereux in Normandy; the triforium was after the triforium of Chartres Cathedral; the façade was edited down to a modified version of Notre Dame’s façade, but he kept his open bay bell towers from his original design.

By March 1894, with plans in hand, permits obtained, contractors hired, and a construction schedule established, Bishop Maes was ready to officially break ground. Though he still felt the preliminary costs were steep, he knew these could be negotiated as work progressed. But his overriding argument for building such a house of worship was expressed in an article he wrote for the “American Ecclesiastical Review” in 1894. “Our zeal in building churches must be a starting point toward a reviving love for Jesus Christ whose Tabernacle is erected therein,” he wrote. “Lack of traditions will make it somewhat more difficult to arouse the enthusiasm of the faithful, but the personal sacrifices which they have made to build the temple can be successfully used as a lever and as an interested incentive to make them adore and love with more exterior, and especially with more convinced interior devotion, the Divine Treasure enshrined therein.”

When Bishop Maes sank the blade of his shovel into the earth in April 1894 to break ground for Covington’s new St. Mary’s Cathedral, he had high hopes that construction would commence quickly and proceed without incident. In the weeks that followed, engineers and workmen descended on the site and began surveying and excavating the ground according to the architect’s plans. Heavy equipment moved in and steam shovels hissed and scooped, transforming the site into a beehive of activity. Coquard’s plans called for them to dig down 25 feet along the foundation perimeters, where piers could be sunk that would support the massive weight of the cathedral super structure. But as larger and larger steam shovel buckets of earth were scooped out, supervising civil engineer Willis Kennedy noticed a big problem. While hoping to find a stable ground for construction, he found instead only a wet, marshy soil with layers and layers of sand and clay. It didn’t look good. He knew immediately it was the type of soil upon which no cathedral could be built.

Kennedy broke the news to a stunned Bishop Maes as best he could. He was devastated. The ground was what engineers called a “compressible” soil, one that was not uniform throughout and could never support the weight of a massive building. Yet, Kennedy tried to reassure the bishop that there were a few things he could still try in hope of resolving the problem. Yet he could not guarantee that any of them would work.

For the first time since becoming Bishop of Covington, Camillus Paul Maes found himself with the wind completely out of his sails.

Next time: “Out of struggle and hardship, Covington’s new Cathedral is born.”

Stephen Enzweiler is the Historian and Archivist at the Cathedral Basilica of the Assumption in Covington.

Paul A. Tenkotte, PhD is Editor of the “Our Rich History” weekly series and Professor of History at Northern Kentucky University (NKU). To browse more than ten years of past columns, see: https://nkytribune.com/category/living/our-rich-history/. Tenkotte also serves as Director of the ORVILLE Project (Ohio River Valley Innovation Library and Learning Engagement). For more information see https://orvillelearning.org/. He can be contacted at tenkottep@nku.edu.