By Howard Whiteman

Murray State University

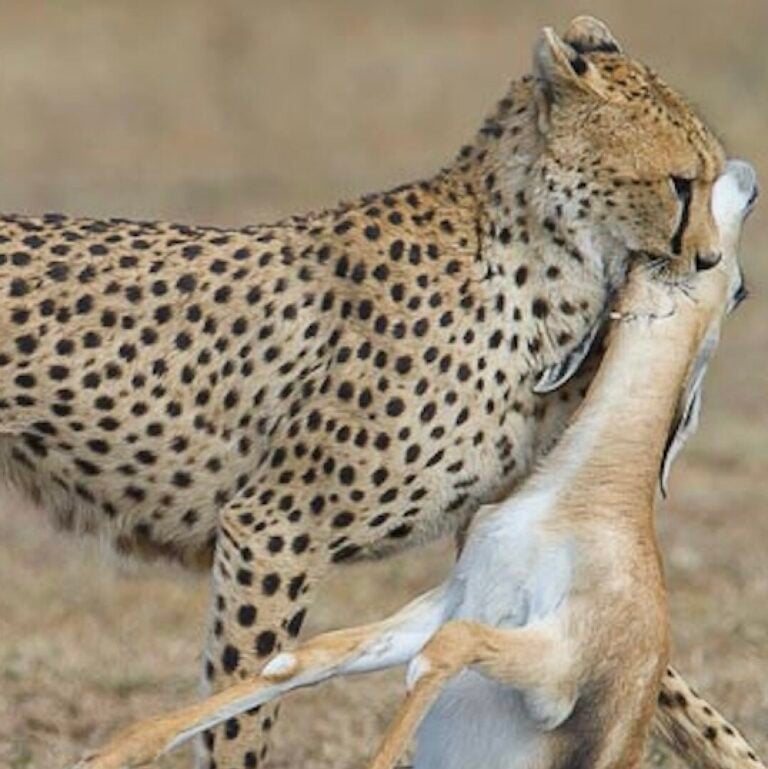

I am transfixed by an Instagram feed that shows nature about as raw as it gets. In one video, a lioness runs across the savannah, bypasses an adult female antelope, and grabs her fawn. In another, a bobcat chases down a songbird in someone’s backyard. That same ecological interaction is repeated again and again with a grizzly grabbing a calf elk, a crocodile death-rolling a zebra, and so many others.

Of course, the Instagram feed is called “Nature is Metal.” I highly recommend it.

It is well named because nature is metal, if you think about the sort of brutally honest, hard-core music that many of us know and love. Metal is harsh to some people, and even those who enjoy it don’t like all of it. But nature is like metal in the sense that metal is brutally honest about life. Nature is really focused on two things: survival and reproduction. I’m pretty sure that one of those two things are in almost every metal song I’ve ever listened to. Sometimes metal is so stark it’s like a someone tossing a freezing bucket of water on you. The music is literally telling you to wake up, look around, and realize that this is how the world really works.

One reason we humans think that nature is metal, rather than just thinking nature is nature, is because we are so separate from it. Our food comes in cellophane packages or cardboard boxes, pre-cut, pre-cooked, and most certainly pre-death, sometimes delivered to our doorsteps. Farmers, hunters, and anglers know the intricacies of how a live animal becomes a meal, but for many that insight has been lost, and, for them, it is better that way.

We cringe at death and violence because we rarely experience it ourselves, because we have created a society that, in many cases for the better, doesn’t allow either of these things to be commonplace or accepted. Except, of course, when we glorify it in movies, television shows, sports, and video games. But that is either fictional or regulated, sometimes even simulated violence, with rules, right? Real death and violence are just that: real. Like nature, and metal: reality.

We should be outraged when we see the indiscriminate killing or cruelty of animals for no other purpose than “pleasure,” or when we see brutal beatings and violent deaths among our fellow citizens, no matter what the purpose or reasoning behind it. Humans have morality, which is why we should be outraged and care about others, including non-human animals, and why many of us often find death and violence abhorrent. We don’t want to see it, and we close our eyes and wish it would go away.

For some parts of our life, that can happen. We can buy frozen wings wrapped in plastic and never give a thought about the dozens of chickens that died to help make our football weekend tastier. We can ignore the roadkill that litter our highways, not thinking about the price other animals pay for continued human progress and efficient commutes. We can find entertainment in Instagram feeds and gasp at the utter brutality of nature. Nature is only for animals; we are separated from it and them. They are different; we are not like them, we think, even as we primp the same hair, claws, and teeth that we share with lions, squirrels, gorillas, and other mammals.

It is more difficult to wish human violence away. When protestors are beaten or killed, even metal skips a beat. When laws are ignored and thugs are unleashed on innocent people, it’s definitely metal. When wars break out over dwindling resources, or leaders decide to take over other countries by force, it’s metal. If we are really that different from other animals, we certainly don’t act like it. Human violence is as metal as it gets, and is tough to ignore.

We are all metal, whether we like it or not, whether we appreciate it or not, or whether we choose to live in the reality-based system we call nature or not. Death and violence happen, and we use that death and violence every day to attain our goals, whether it is food for the table or order in the streets, and whether we are pulling the trigger or someone else is doing the dirty work for us.

What we have to ask ourselves, as humans, is how much metal is enough? Where do we draw the line on our own morality, the one thing that helps set us apart from some, but not all animals, as far as we can tell? Death and violence will always be a part of our lives, because they are natural parts of life, but like other animals, we can choose when and where such behavior is appropriate.

We can make such choices because nature and metal are not just death and destruction. They are empathic, compassionate, and even cooperative.

Many non-human animals are social, and work together to create great societies. Consider ants, honeybees, and other social insects, which live in large colonies to serve a common goal. Look at communally breeding birds, like cliff swallows, great-blue herons, and penguins, which coexist because the benefits of cooperatively living together are better than trying to live alone. Look at how herding animals warn each other of approaching predators, and protect the young, even when they are not related to them. Look at how species groom each other, court each other, take turns watching for danger, care for their offspring, and play together, and you quickly realize that all of these are just as much a part of nature as death and violence.

Yes, nature is metal, because both nature and metal are life. Nature and metal are not constrained by human-imposed, artificial constructs about how we would like to believe the world works. The world works the way it always has, through nature, the same nature that our own species evolved with, and the reason that we are the deadly, violent, empathetic, compassionate, cooperative species that we have become. That is the beauty of living in a natural, very metal, world: it’s reality.

Whether we like it or not, humans are part of nature and not apart from nature, and how we live our lives and which metal we listen to is, and always has been, up to us. One question remains: what are you listening to next?

Howard Whiteman is a professor of wildlife and conservation biology, director of the Watershed Studies Institute, and the Commonwealth Endowed Chair of Environmental Studies at Murray State University. He is a columnist for the NKyTribune.