By Berry Craig

NKyTribune columnist

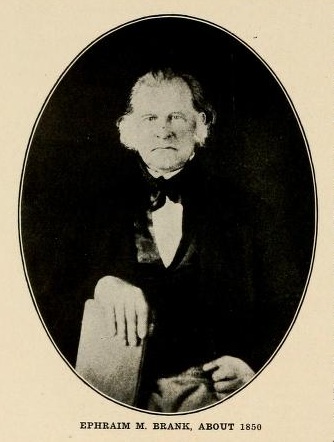

Friend and foe remembered Lt. Ephraim Brank’s marksmanship in the Battle of New Orleans.

The Muhlenberg countian was a hero to the victorious Americans. He was “some great spirit of death” to the vanquished British.

“We lost the battle,” a Redcoat officer lamented, “and to my mind, that Kentucky rifleman contributed more to our defeat than anything else.”

Fought on Jan. 8, 1815, the battle of New Orleans was the bloodiest clash of arms in the War of 1812. Ironically, the war was technically over.

Unknown to either army, American and British emissaries meeting in Ghent, Belgium, agreed to a peace treaty on Christmas Eve, 1814. The U.S. delegation included House Speaker Henry Clay of Lexington.

The war officially ended on Feb. 16 when the U.S. Senate ratified the treaty. The next day, President James Madison declared the war was over.

Leader of the “War Hawks” in Congress, Clay had helped egg on the conflict, which ended in a draw. Neither money nor territory changed hands; both armies went home, Brank to Greenville, the Muhlenberg County seat.

His Bluegrass State comrades-in-arms told and retold the story of him bravely standing alone atop the battlements at Chalmette plantation, southeast of the Crescent City, gunning down enemy soldiers as calmly as he bagged squirrels in western Kentucky.

Throughout the fierce fight, two soldiers kept loading and reloading rifles and handing them up to him. The 24-year-old Bluegrass State sharpshooter never missed, or so the tale was told.

A lawyer, land surveyor and farmer, Brank is a hero in Greenville. There is a Brank Street; a life-size bronze statue of the marksman, armed with a Kentucky long rifle, stands in the Veterans Mall at the courthouse.

“Lt. Brank’s rifle is oriented so that it is aiming toward the battlefield in Louisiana,” says the Tour Greenville Internet website. The statue is “the only sculpture commemorating the War of 1812 in Kentucky,” the website also advises.

A “Brank Historic Exhibit” is in the county public library’s Genealogy and Local History Annex across the street. The display includes “an historically accurate long rifle and powder horn along with a life size cardboard Brank stand-up for a unique Greenville photo-op,” according to the website.

The old soldier is buried in an honored spot in Old Greenville Cemetery, close to city hall. A state historical marker at the graveyard cites him as a “distinguished war hero of 1812,” though a simple military tombstone marks his final resting place.

The statue, library display and the grave comprise the “Lt. Ephraim Brank Memorial & Trail.”

Born in North Carolina in 1791, Brank settled in Muhlenberg County about 1808.

“Captain Brank was a man of stately proportions and wonderful physical constitution,” Otto A. Rothert wrote in History of Muhlenberg County. “He was a ‘crack shot’ and an enthusiastic hunter: a well-read and a resolute and systematic man, and very kind to those with whom he came in contact.”

His hospitality did not extend to Redcoats.

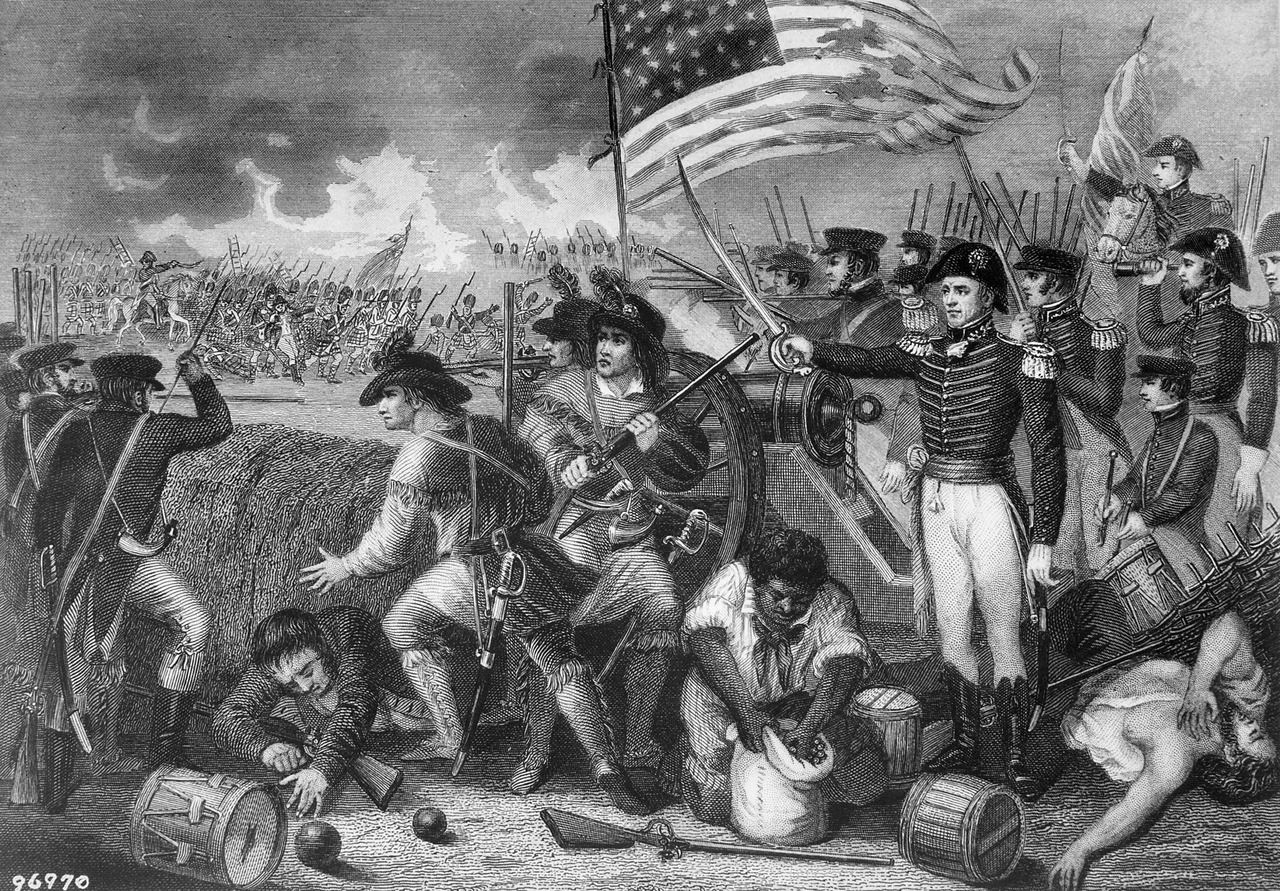

Brank was among several Kentuckians in Gen. Andrew Jackson’s 4,500-man hodgepodge army. “Old Hickory’s” force included Louisiana, Tennessee and Kentucky militia, frontiersmen, regular soldiers, sailors and marines, free African Americans, Native Americans, local volunteers, inmates from the city jail and even a band of pirates.

At Chalmette, Jackson and his men dug in behind the Rodriguez canal. The ditch, 15-feet-wide and eight-feet deep, ran 3,000 feet from the river to a swamp.

The Americans called their position “Line Jackson.” Their works were hastily constructed of dirt, barrels of sugar, cotton bales and timber with openings at intervals for cannons.

The defenders had a clear field of fire. Flat, open ground—a harvested sugar cane patch—stretched in front of them.

Undaunted, the British, 5,000-strong, charged with bayonets fixed. The Americans, whom the Redcoats scorned as “dirty shirts,” refused to budge. They aimed a deadly storm of rifle, musket and cannon fire at the attackers, forcing them to withdraw.

The British regrouped and charged again–with the same disastrous results—-before retreating and ultimately leaving Louisiana aboard the ships that brought them.

The lopsided fight lasted about 30 minutes. British losses were 285 killed and 1,265 wounded. Another 484 were taken prisoner or were listed as missing, according to the U.S. Army Center of Military History’s website.

The Redcoat commander, Gen. Sir Edward Packenham, was among the British dead. His body was sealed in a barrel of rum and transported to London for burial in St. Paul’s Cathedral. Packenham’s wife had come along; she had expected to be at his side after he captured the Crescent City.

American casualties included 13 dead and 30 wounded. Another 19 were reported captured or missing, the website says.

How many enemy soldiers Brank slew is unknown.

But the British officer, whose account of the battle Rothert included in his book, said Brank was plainly visible, standing alone on the breastworks, where “he seemed to grow, phantom-like, higher and higher, assuming, through the smoke the supernatural appearance of some great spirit of death.” The Redcoat added, “Again, did he reload and discharge and reload and discharge his rifle, with the same unfailing aim, and the same unfailing result.”

As the British neared Line Jackson, they were shrouded by thick battle smoke. It was, the officer remembered, a time of “indescribable pleasure” because it hid them and shut “that spectral hunter from our gaze.”

The officer described Brank as “…a tall man standing on the breastworks, dressed in linsey-woolsey, with buckskin leggings, and a broad-brimmed hat that fell around his face almost concealing the features. He was standing in one of those picturesque graceful attitudes peculiar to those natural men dwelling in forests.”

Actually, Brank dwelt in a comfortable house in Greenville, where he died in 1875 at age 84. “Ephraim McLean Brank’s heroic act on the breastworks in the battle of New Orleans…is one of the most thrilling incidents recorded of any Muhlenberg man, as it is a fine one in our national history,” Rothert wrote.

Brank’s bravery earned him a promotion to lieutenant the day after the battle, according to the Greenville tourism website. A “Ballad of Ephraim Brank” was composed in his honor.

The very spot where he mowed down the Redcoats is long gone. “Line Jackson,” was dismantled following the battle. Reproduced earthworks, studded with cannons, are the main attraction at Chalmette Battlefield national park.

For many years, Kentuckians and many other Americans celebrated Jan. 8 as fervently as they did July 4. The battle of New Orleans made Jackson a national hero. He was elected president in 1828 and re-elected in 1832.

Historians on both sides of the Atlantic still debate what might have happened had Old Hickory lost at New Orleans. Would the British have revoked the treaty? Would they have held the city hostage for better terms?

At any rate, relations between Mother Britain and her cantankerous former American colonies improved after the battle of New Orleans. The next time the two nations’ soldiers met in battle—in 1917 in World War I–they were comrades-in-arms.

Berry Craig of Mayfield is a professor emeritus of history from West Kentucky Community and Technical College in Paducah and the author of six books on Kentucky history, including True Tales of Old-Time Kentucky Politics: Bombast, Bourbon and Burgoo, Kentucky Confederates: Secession, Civil War, and the Jackson Purchase, and, with Dieter Ullrich, Unconditional Unionist: The Hazardous Life of Lucian Anderson, Kentucky Congressman. Reach him at bcraig8960@gmail.com