[easy-social-share buttons=”facebook,twitter,pinterest,linkedin,stumbleupon,mail” counters=0 facebook_text=”Facebook” twitter_text=”Twitter” pinterest_text=”Pinterest” linkedin_text=”LinkedIn” stumbleupon_text=”Stumble mail_text=”E-mail”]

Gateway 3: Manufacturers need trained employees at a pace beyond Gateway’s success in providing them

By Greg Paeth

NKyTribune Senior Reporter

Gateway students can leave with a variety of credentials that transfer to other state colleges

Gateway Community and Technical College opened its doors in 2002, some five years after the state created the Kentucky Community and Technical College System, the agency that now oversees a state-wide educational network that includes 16 schools with an enrollment last fall of 87,027, a decline of nearly six percent from the previous year.

Gateway, which had an enrollment last fall of 4,594 full- and part-time students, is the successor to the Northern Kentucky State Vocational School, Northern Campbell Vocational School and the Henry E. Pogue Health Occupations Center, all of which were merged into one school some 13 years ago.

Students can leave Gateway with a variety of credentials. Like the University of Kentucky, the University of Louisville and Northern Kentucky University, the school is accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools’ Commission on Colleges. Gateway’s accreditation is classified as “Level 1” for two-year degrees while the other institutions offer four-year degrees.

Gateway’s accreditation dates to 2008 and was “reaffirmed” in 2013. Its programs are scheduled for another review in 2023. The Southern Association evaluates colleges – big and small – in 11 southern states.

The school offers a wide variety of programs and credentials.

Students seeking an associate of applied science credential must complete 60-68 credit hours, which includes 30-54 hours in technical classes and 15 hours that are considered “general education” requirements, according to Teri Von Handorf, associate provost for academic affairs. The applied science credential is designed for students who want to use that credential to qualify for a job in a technical field. And like students who receive an associate of arts or sciences credential, which requires 60 hours of college credit, a student who completes the applied science program can transfer to a four-year institution.

A diploma designed for a student seeking a job in a technical field requires 36-60 credit hours, which includes six hours of general education classes. Certificates are designed for students seeking “marketable entry-level skills,” Von Handorf said. Certificates range from three credit hours for a “Kentucky Childcare Provider” certificate up to 30 hours for other certifications.

The school’s most prominent – and newest – buildings are located on its Boone County campus, which butts up against I-71/75 in a part of the county that’s not far from the Northern Kentucky Industrial Park and other industrial and manufacturing plants. The campus emphasis is on manufacturing, engineering technology and related trades. It includes the 103,000-square-foot Center for Advanced Manufacturing, a $28.5 million facility that opened in 2010. For the fall of last year, 1,536 students were registered to take classes at the campus. That figure includes students who were taking Boone County Adult Education classes.

The Edgewood campus, adjacent to St. Elizabeth Healthcare’s hospital complex, focuses on nursing and what the school calls “allied health careers.” Gateway said 1,327 students take classes in Edgewood.

Plans call for the Covington/Park Hills campus, high on a hill off of Amsterdam Road, to be closed this year, according to Dr. G. Edward Hughes, president and CEO of Gateway. The school’s cosmetology program will be moved to the Urban Campus in downtown Covington later this year. Hughes said no decision has been made about where three “transportation technology” programs will wind up. There are 219 students at the campus, Hughes said.

Students now attend classes in two of the Urban Campus buildings in downtown Covington, where construction work is under way on two other buildings as the school prepares for the shutdown on Amsterdam Road. The state intends to sell that property. Gateway says the downtown campus will offer course work required for its nursing and manufacturing programs as well as classes in business, information technology, education, criminal justice, graphic arts and early childhood development.

Hughes said 1,302 students were enrolled to take at least one course last fall at the Urban Campus. Another 413 students take Kenton County Adult Education classes in downtown Covington.

Tuition rates for the current school year range from a low of $147 per credit hour for in-state residents to a high of $515 an hour for some out-of-state residents. Out- of-state residents from some contiguous counties in Ohio and Indiana pay $294 an hour. All students pay an additional $4 per hour for a program called “BuildSmart,” which provides funds for capital projects at community colleges throughout the state.

For the past few years, Gateway Community and Technical College president and CEO G. Edward Hughes has been lauded for his leadership in creating an $80 million Urban Campus in Covington that is considered to be a key element of a broader plan to breathe new life into a downtown that no longer bustles.

From Gateway’s perspective, that campus should make post-secondary education more accessible and attractive to thousands of students in Northern Kentucky.

Gateway even received some national attention in September when Hughes was one of three college presidents who participated with U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan in a national conference call that announced that Gateway was one of 24 U.S. colleges to receive a $3.6 million grant through the government’s “First in the World” program.

That grant was earmarked for increasing access to college and improving graduation rates so the United States could claim worldwide leadership in the percentage of citizens with college degrees.

But all of the news hasn’t been good. Praise for Hughes and Gateway’s overall performance has not been universal, and the sources of criticism cannot be dismissed lightly.

An increasingly active and vocal board that oversees the school has been pressuring Gateway’s top executive on issues related to governance and performance. (See related story on the thorny relationship between Hughes and some board members.)

Northern Kentucky manufacturers also have raised questions about the school’s inability to produce enough graduates to fill jobs that are available today, those that will open up in the near future and the availability of workers for companies that might want to locate in the region.

Ten years ago, Northern Kentucky manufacturers such as Mazak and LSI Industries worked with a long list of organizations in the region and local political leaders to lobby the legislature for money to build what became Gateway’s Center for Advanced Manufacturing, a $28.5 million learning and training facility immediately east of I-71/75 in Boone County, north of Mt. Zion Road.

As the region’s community and technical college, Gateway was created to be a primary source for technical school graduates who would, in theory, fill jobs in the region. The school also emphasizes its close relationship with manufacturers who comprise one of the school’s most important constituent groups.

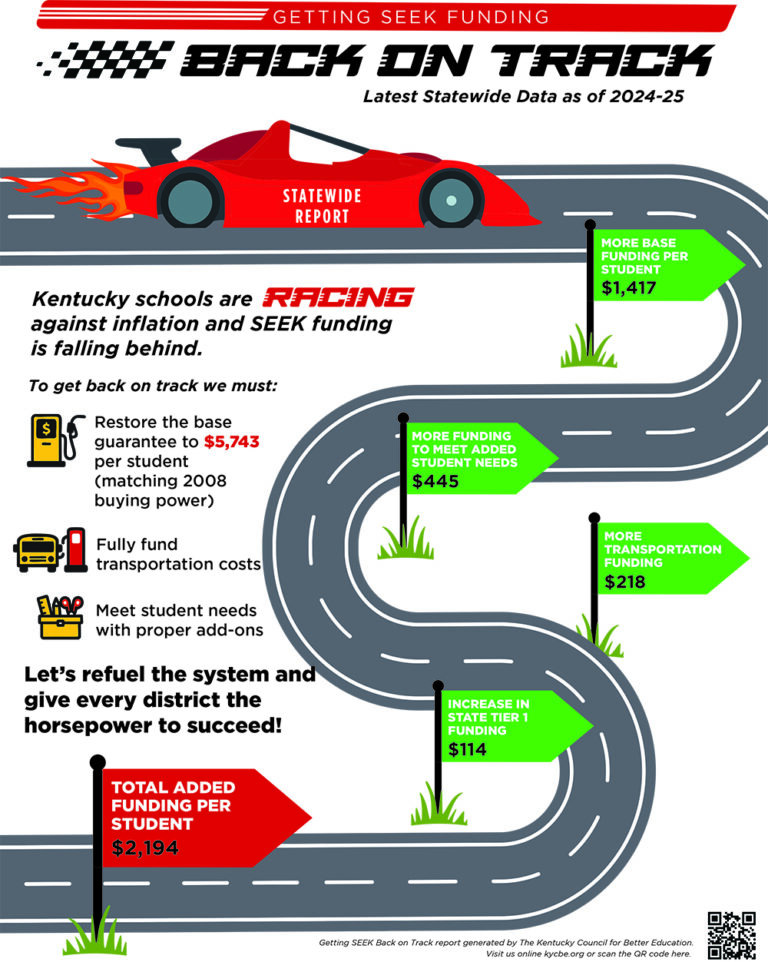

In making its case 10 years ago for state funding for the Center for Advanced Manufacturing, Gateway projected that about 620 jobs would open up in each of the next 10 years. That job estimate has remained fairly constant since 2005. It is based on an average of 360 Baby Boomers retiring each year and roughly 250 employees leaving due to routine workplace turnover.

Equally consistent is Gateway’s inability to meet its goal of graduating 600 or more students each year in its manufacturing programs.

From 2010 – when the manufacturing center opened – to 2014, 296 students completed the program, according to a strongly worded letter sent to Hughes last November by the judge-executives in Boone, Campbell and Kenton counties and the top executives at the Northern Kentucky Chamber of Commerce and Northern Kentucky Tri-ED, an economic development agency that focuses on retaining businesses and attracting new businesses to the region.

The letter was a response to a Gateway report that had been released a month earlier that projected that 675 people would complete the program over the next five years. That averages out to about 135 per year, far short of the 620-per-year target.

“Industry leaders have met with us and have expressed dissatisfaction with the Gateway 2014 report,” the letter said. “A pipeline of skilled labor is critical to the success of Northern Kentucky.”

Toward the end, the letter said, “The Gateway 2014 report does not meet the need of our community to fill the existing and projected openings, much less any new industry … and we formally request a revised plan.”

The letter asked Hughes and Gateway to “go back to the drawing board” and develop a strategy to meet the 600-plus graduate goal.

Eleven days after the letter was written to Gateway, the college announced the creation of the Advanced Manufacturing Workforce Development Coalition, an organization whose membership included the judges who had signed the letter as well as the chamber, Tri-ED, Gateway and a long list of other agencies.

Although the tone of the Nov. 7 letter indicated that the signers wanted to play hardball with Gateway for its shortcomings, Tri-ED president and CEO Dan Tobergte was consistently upbeat when he answered questions about an early January meeting between the coalition and representatives of the Northern Kentucky Industrial Park Advisory Committee for Continuing Education, a nonprofit agency created to help manufacturers fill jobs at their plants.

He said the manufacturers seemed to have a favorable reaction to a coalition plan that calls for a more aggressive effort to attract more students to the Gateway manufacturing center. Part of the effort focuses on making parents and educators more aware of the program, said Tobergte, adding that the management group asked the coalition to “refine” parts of the plan.

“It’s not just Gateway’s issue,” Tobergte said. “We’ve got a great problem here. We’ve got jobs, and we’ve got companies that want to fill their jobs.”

Problems with the manufacturing center are both a “community issue and a regional issue,” Hughes said. “I’m convinced – and I’m not going to give you a number – but I’m convinced this effort is going to bear a lot of fruit for everybody, most importantly for the manufacturers.”

R. Richard Jordan, who served on the Gateway board from its inception until he was replaced last year, is a retired executive from LSI Industries, a Cincinnati-based company that has a manufacturing plant in Northern Kentucky. He is also president of the industrial park advisory committee, which has pushed for better performance by the manufacturing center.

Some manufacturers are frustrated because they believe they invested plenty of time and political capital in convincing the state to spend $28.5 million on the Gateway center only to have its program fall far short of its goal, Jordan said. One common comment was, “We wasted all this time and energy and this is all we get?” Jordan said.

“One of the key things from our standpoint is that we’re getting the top community leaders’ attention about this problem, and they want to solve it,” Jordan said after the advisory committee, Gateway and other members of the coalition met last month. “From the manufacturers’ point of view, they feel the issue has been elevated to the proper level. It’s getting attention and it’s not a shotgun approach. We think the coalition will get people laser-focused on this issue.”

Jordan, who raised questions about the manufacturing center at two Gateway board meetings last year – one when he was on the board, the other after he had been replaced – summed up the attitude of the manufacturers this way: “OK – the planning looks good. Now, what are the results?”

A group of manufacturers has taken special steps to try to fill jobs at their plants, Jordan said. They are spending $18 million on 90 employees who will go through apprenticeship programs at their companies, which will pay the tuition for students who attend classes at the Center for Advanced Manufacturing, he said. The $18 million figure includes the full-time salaries of employees, some as much as $50,000 per year, while taking Gateway classes part-time in the evening.

About a week before the early January meeting, Gateway board vice chair Ken Paul said some similar things.

“We have to be more aggressive to get the students in the door” for the program, said Paul, who has been on the board since Gateway was created in 2002. “The number one item is the perception of manufacturing,” he said, adding that many people believe factory work involves “dirty old jobs that are mundane” and don’t pay much. “That’s just not the case today.”

Ten years ago, when Gateway was making its case for state money to build the Boone County center, the school said Tri-ED pegged the annual manufacturing salary at $43,000 or $55,900 when benefits were included. Jordan said earlier this month that completing the two-year program, which would cost about $13,000, would open the door for jobs that might have a starting salary between $35,000 and $50,000.

Gateway board raises questions regarding high default rate

Gateway Community and Technical College board members raised questions in 2014 and again this year about student loan default rates that are among the highest in Kentucky and considerably higher than the national average for at least the past three reporting periods.

Figures released last September showed that Gateway’s default rate was 32.5 percent for students who had failed to begin repaying federal student loans as scheduled in 2011. That percentage ranked second in the state to Somerset Community College, where 33.3 percent of the students were considered to be in default during the same time period.

The Gateway default rate released in 2013 was 29.5 percent, fifth highest in the state, while the rate a year earlier was 27.7 percent, third highest among its peer group of 15 other schools in the Kentucky Community and Technical College System.

There is about a three-year lag between the time when a student is supposed to begin repaying a loan and the time when the loan is classified as “in default.” The clock, in effect, begins running during the year in which repayment of a loan is scheduled to begin. The loan is considered in default if the student hasn’t started making payments within two years after that first year for repayment has elapsed.

The three-year time frame reflects a relaxation of lending rules that Congress approved in October 2009. Before that, loans were in default if payments were not being made within a two-year period.

Gateway’s rate released last year was 57 percent higher than the national average of 20.6 percent for public community colleges. For the two years before that, the Northern Kentucky school exceeded the national average by 41 percent and 51 percent, respectively, according to information from Gateway and the U.S. Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics.

And although public community colleges are, on average, less expensive than other colleges, those in the Kentucky system are the most expensive among the 16 states that are members of the Southern Regional Education Board, the Atlanta-based agency whose responsibilities include the accreditation of colleges, including Gateway.

For the 2011-12 academic year, Kentucky’s tuition and fees averaged about $4,100 while the median charge for the 16 states covered by the southern board as well as the rest of the country was about $3,000, the education board said. Only six states charged students more than Kentucky for that school year, the regional board said.

The southern regional board also said that for the poorest people in Kentucky – households in the bottom 20 percent – that $4,100 figure represented about 30 percent of a household’s median income of about $13,600. That percentage was the highest in the country for the poorest Americans and was about 12 percentage points higher than the national average of 18.1.

Gateway board chair Jeff Groob, vice chair Ken Paul and former board member and board chair R. Richard Jordan, who served until mid-2014, identified the high default rate as one of their major concerns about the college.

At a board meeting last October, Groob called the default rate one of the most serious issues Gateway must address. Earlier this month, Groob restated his concerns. “I would settle for being just average or at the median here,” Groob said. “Of course, I’d like (Gateway) to be best in class, but when compared to the other schools, being 15th out of 16 is just not acceptable.”

“The student loan issue is something we have to discuss,” Paul said in an interview in which he noted the “huge default rate” in Somerset, which had the highest rate for two of the last three years. Hazard Community and Technical College had the worst non-payment rate, 34.4 percent, for data released in 2013, the government statistics showed.

Hopkinsville Community College had the lowest default rate, 17.7 percent, last year among public community colleges in Kentucky. West Kentucky had the lowest rate – 18.8 percent – two years ago while Madisonville had the best rate, 15 percent, for numbers released in 2012.

Although Gateway’s rates are high, falling behind on college loans for both two-year and four-year institutions isn’t unusual in the Commonwealth.

Kentucky’s overall default rate for 2014 was 17.5 percent, fourth worst in the country with 11,706 students in default while 66,701 were considered “in repayment.” Only New Mexico (20.8 percent), Arizona (18.4) and W. Virginia (18.2) had higher percentages of students who weren’t repaying their loans on schedule, according to government reports that reflected data for public, private and for-profit institutions.

Comparable default rates nationally were 13.4 percent in 2012, 14.7 percent in 2013 and 13.7 percent last year for all public, private and for-profit colleges, including both two- and four-year schools.

During an interview in January, Gateway President and CEO G. Edward Hughes referred questions about the default rate to a highly detailed Gateway press release that was made public in immediate response to a U.S. Department of Education report that showed the school’s default rate had topped 32 percent.

“The good news is that nearly 70 percent of Gateway student borrowers that year met their obligation to repay their loans,” the press release said. “Many of the individuals in default are facing financial crises and are simply unable to begin repayment now and may begin repayment later. A small percentage of those students in default are ‘scamming the system’.”

Hughes emphasized that the three default rates reflected payment histories that went back three years before students were determined to be in default. He said, for example, that the 2011 default rate reflected data for 395 students who would have entered Gateway during the 2008-09 school year.

Gateway also stressed that the school was not facing sanctions because of the high default rate. Schools with default rates higher than 30 percent for three successive years can lose their eligibility to participate in federal financial aid programs, according to the Education Sector, which is part of the American Institutes for Research based in Washington, D.C.

The two-page media release from Hughes outlined a long list of steps that have been taken to address the issue, including the creation of a “default management team.” He also pointed out that schools like Gateway experience higher default rates “…because we serve a disproportionately higher rate of students from financially challenged situations.”

In the time period that was examined by the study, Gateway tuition averaged about $3,200 per year, the Education Sector said.

In July of 2013, Gateway was one of 265 post-secondary institutions in the country that were labeled “Red Flag” schools because the default rate was higher than the graduation rate, according to research by USA Today and the Education Sector. The report focused on Gateway’s default rate of 27.7 percent that was released in 2012. At the time, Gateway’s graduation rate was 27 percent, the Education Sector said.

Andrew Gillen, who wrote the report for the research firm, said the data has not been updated since July 2013 and he wasn’t aware of any similar research that compared graduation and default rates.

Of the 265 schools that received the “Red Flag” designation, 88 were community colleges like Gateway. Besides Somerset, Bluegrass Community and Technical College in Lexington also made the “Red Flag” list.

Bluegrass had a default rate of 21.2 percent, four points higher than its graduation rate, while Somerset’s default rate was 28.4 percent compared to a 25 percent graduation rate. Two other private two-year colleges in Kentucky also made the list.

“These colleges should set off a red flag in the minds of prospective student borrowers—and their parents,” the report said. “Many students at these colleges will no doubt take out loans, graduate, and get good jobs. But the high default rates and lower graduation rates suggest that many students will not.”

The report made it clear that there are numerous reasons why people don’t repay student loans. But it also said default rates are significant because they “…provide an objective and quantifiable measure of a college’s success in providing a cost-effective education. For many students, the main reason for enrolling in college is to improve their lifetime financial well-being, and a high default rate indicates that a college has failed to help its students achieve this important goal.”

Editor: Mike Farrell, NKyTribune Special Projects Editor

[easy-social-share buttons=”facebook,twitter,pinterest,linkedin,stumbleupon,mail” counters=0 facebook_text=”Facebook” twitter_text=”Twitter” pinterest_text=”Pinterest” linkedin_text=”LinkedIn” stumbleupon_text=”Stumble mail_text=”E-mail”]

This is a national issue that will take the combined efforts of the education, parents and business to solve. Introducing students to business people and business settings as early as fourth-grade, is critical to changing the perception of manufacturing dating back to the industrial age. Reeducating students and parents is a key element in this approach. Like it or not, one of the most important elements of the Common Core is experiential learning and it begins in grade school. To build on that and get students out of the classroom and into the workplace in some capacity, will help them develop their own ideas about where they see themselves in the workplace. Students that participate in tours, shadowing, internships, and co-ops have a much greater understanding and appreciation of the opportunities they may want to pursue by the time they graduate from high school and college. The other critical piece is to add workplace training as part of the all teaching degrees. When teachers see what the workplace expects from their students, they can better understand how to approach the subjects they teach. The goal is not to Pidgeon hole students but to open their eyes to the vast world of work. If what they see looks interesting, inviting and challenging, the rest should take care of itself.

The elephant in the room here is that the school districts feeding Gateway are not producing a sufficiently-educated base of graduates to successfully complete the level of achievement needed by the manufacturers. Until we can create a reasonably well-trained cadre of high school graduates in the region, Gateway will struggle to produce qualified graduates….