By Al Cross

Special to NKyTribune

Brent Yonts has dozens of plaid sportcoats. Most are pretty sharp; others not so much. The state representative from Greenville has adopted the motif as his sartorial trademark, and it’s a fixture in the General Assembly.

Yonts is stuck in a fashion rut, and so are too many of his Democratic colleagues in the state House, by opposing legislation to make public the payments legislators will get from their generous pension system.

That idea has gotten more traction lately because the sorry condition of the state’s other pension funds is the overarching issue of the legislative session. A committee of the Republican-controlled Senate approved a pension-transparency bill Wednesday, but in response Yonts sang the same old tune:

“If you’re in public office or if you’re a public employee, then what you’re currently earning as salary should be public information, and it is,” he told the Lexington Herald-Leader. “Once you’ve retired, though, what you draw from retirement benefits is nobody else’s business.”

No. The spending of any public dollar is public business. And seeing just how great the pensions are would more clearly illustrate the effect they have on legislative behavior. In 36 years of following the General Assembly, I’ve become convinced that too many legislators are too interested in staying in office rather than doing the public’s business.

In 1980, the same year legislators secured their independence from governors, they created a pension system that they have since made overly generous – an attractive nuisance, a legal term for something that causes harm through its appeal. The latest example of their self-generosity was a law allowing legislators to greatly increase their pensions by taking jobs in other branches of government. That can produce a six-figure pension based mainly on part-time service.

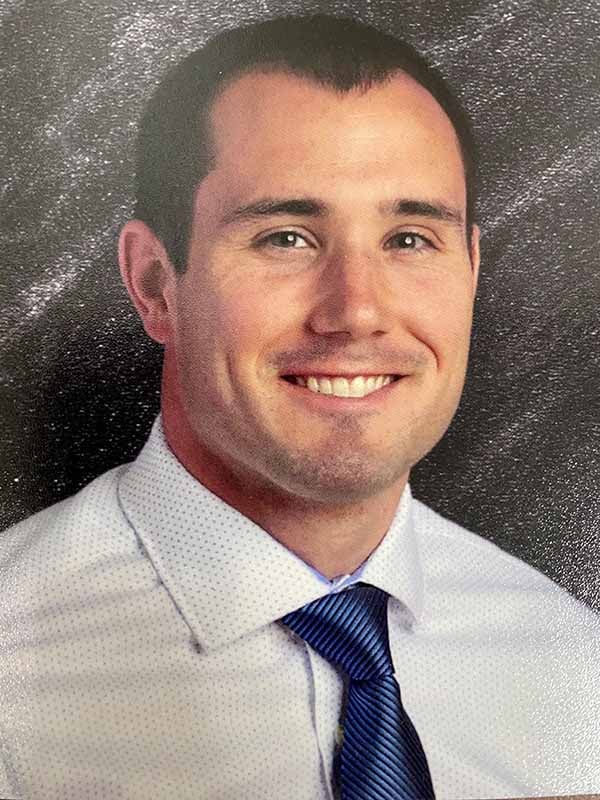

“The legislative enhancer is really what’s going to blow people’s minds,” said state Rep. James Kay, a Versailles Democrat who says he supports pension transparency and another good idea – giving legislators the same pension rules as those for regular state employees.

“It would probably be better funded in the future if all legislators were in it,” Kay said, noting that the regular-employee system has only 17 percent of the money needed to pay current members. The legislative pension fund, which is very small, relatively speaking, is 85 percent funded.

Kay said he doesn’t expect the House to pass Sen. Chris McDaniel’s transparency measure, Senate Bill 45, because members don’t want their pensions revealed. He’s been in the legislature less than three years, but he knows it well; his mother has worked there 20 years, and he was legal counsel to House Speaker Greg Stumbo in the 2013 session.

Despite that background, Kay filed on Friday a bill to impose term limits on legislators – and he is working on another that could take away from them the power to draw their own districts and give it to an independent commission.

Such legislation has gone nowhere in the past, and it has usually been sponsored by Republicans. Now, House Democrats may lose control of the chamber and there is a strong anti-government feeling in the land, heightened by partisanship in Washington and the successful appeals of populist presidential candidates in both parties.

Kay says that’s not why he’s pushing term limits and redistricting reform, but he acknowledged that in the current political environment it would be good politics for Democrats to embrace long-needed changes.

“The people want it because people want reform,” he said of term limits. “I’ve seen how entrenched incumbents serve special interests and self-interest rather than the interests of the people.”

Kay’s House Bill 264 would limit House members to 12 consecutive years of service (six of their two-year terms) and senators to 16 consecutive years (four of their four-year terms). It would require a constitutional amendment, which needs a 60 percent vote in each chamber and approval by a majority of voters in a statewide referendum this fall. It would take effect in 2018.

Kay argues, “The power of incumbency is pretty much unbroken, and I think we’ll have more opportunity to get things done when you have outgoing senators and representatives who can vote their conscience more often.”

Correct. During most of the decades I’ve watched the legislature professionally, I’ve thought term limits were a bad idea because I saw how public-spirited, long-tenured legislators gained knowledge, influence and power that they often put to good use, leading their colleagues to cast politically difficult votes.

But that didn’t happen often enough, and now that pensions are so lucrative, and legislative elections so expensive, funded largely by lobbying interests, it’s time to stop this merry-go-round. The most compelling reason is tax reform, which the state has needed for 30 years but would require overcoming intense lobbying by powerful interests that want to keep billions in tax breaks.

House Republican Leader Jeff Hoover says most of his caucus would support term limits. Kay said the five House Democratic leaders “gave me the go-ahead” to introduce the bill. “They obviously don’t dictate what I do,” he said. “Some of them thought it was a good idea and others didn’t have a comment.”

Senate President Robert Stivers probably reflects the prevailing view: “There is something to be said for institutional knowledge,” he said, and voters “have the ability to limit out terms.” But Kay says, “An incumbent can get too entrenched, in my opinion, extremely entrenched, and we get the same results over and over.” And those results haven’t been good enough.

Al Cross is director of the Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues and associate professor in the University of Kentucky School of Journalism and Telecommunications. His opinions are his own, not UK’s. This article originally appeared in the Louisville Courier-Journal and is reprinted here with permission.